1. Why visit the exhibition?

To celebrate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death on 2nd May 1519, the Royal Museums of Turin is hosting an exhibition called “Leonardo da Vinci. Drawing the Future” (Leonardo da Vinci. Disegnare il future). As a huge fan of Leonardo, I went to Turin immediately. Here are some reasons why you shouldn’t miss the exhibition.

- The exhibition displays over fifty works which illustrate Leonardo da Vinci’s studies of art and science.

- Most of the exhibits come from the permeant collection of autograph works by Leonardo in the Royal Library of Turin, which includes thirteen drawings purchased by King Charles Albert in 1840 and the famous “Codex on the Flight of Birds“, donated by Theodor Sabachnikov to King Humbert I in 1893.

- This is an outstanding set of works, dating from about 1488 to 1515, with a variety of subjects of different inspiration, and one that illustrates Leonardo’s activity from his youth to his full maturity.

- Some drawings are studies for famous works by the great master such as the nudes for The Battle of Anghiari, the horses for the Sforza and Trivulzio monuments, and the splendid study known as the Face of a Young Girl, for the angel in The Virgin of the Rocks.

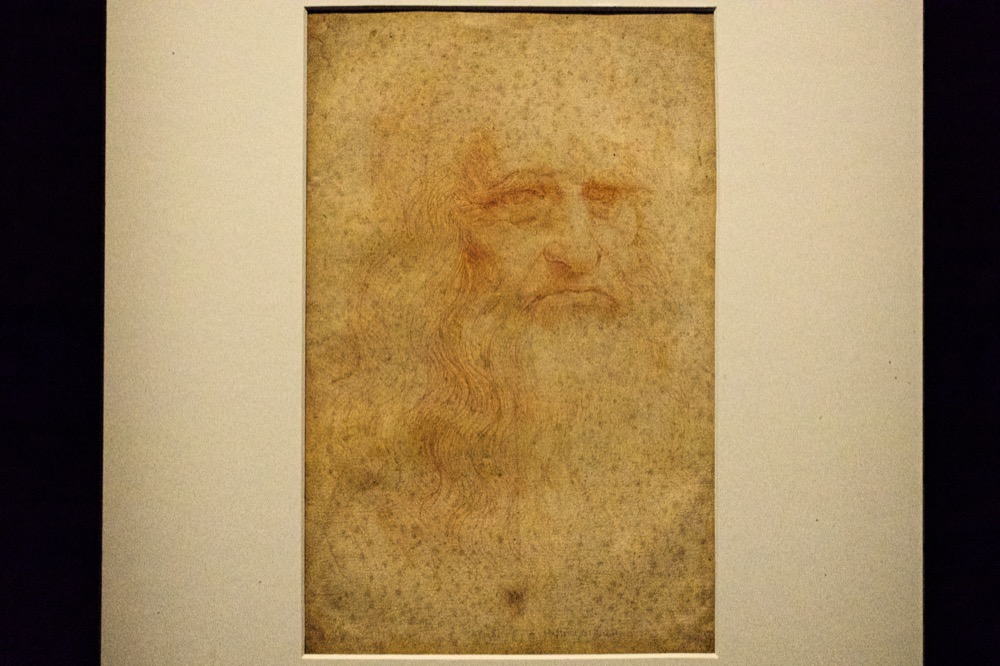

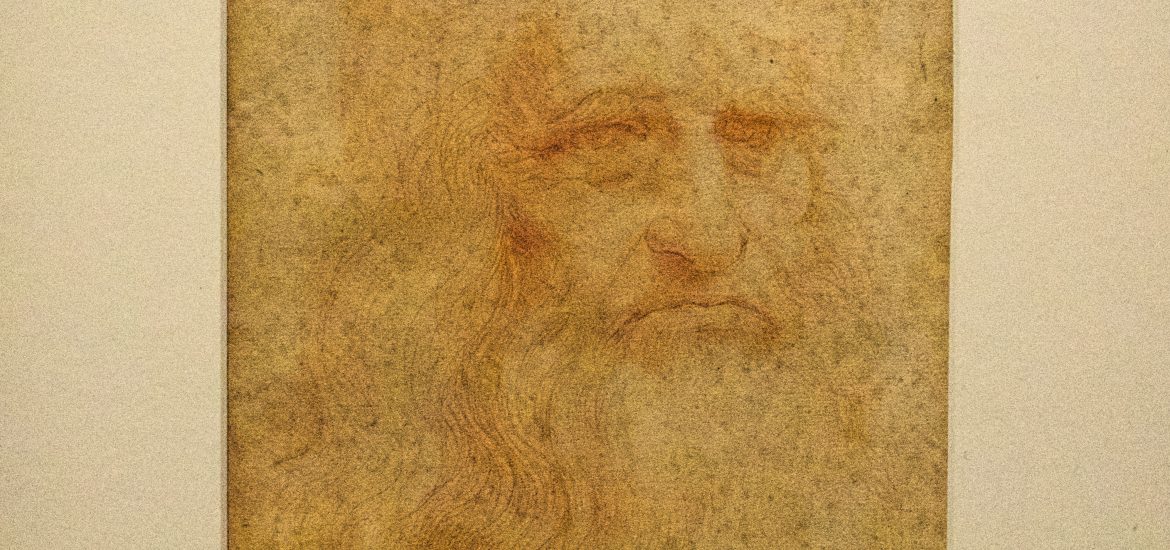

- Also exhibited is the incomparable, universally renowned Portrait of an Old Man, known as the Self-Portrait of Leonardo. Despite being one of the most precious treasures of the Royal Library of Turin, the portrait is rarely shown to the public due to its fragility and poor condition.

- To convey the significance, origin and particularity of Leonardo’s work, similar works by other great masters from the Florentines Andrea del Verrocchio and Pollaiuolo, to Bramante and Boltraffio in Lombardy, through to Michelangelo and Raphael are also displayed.

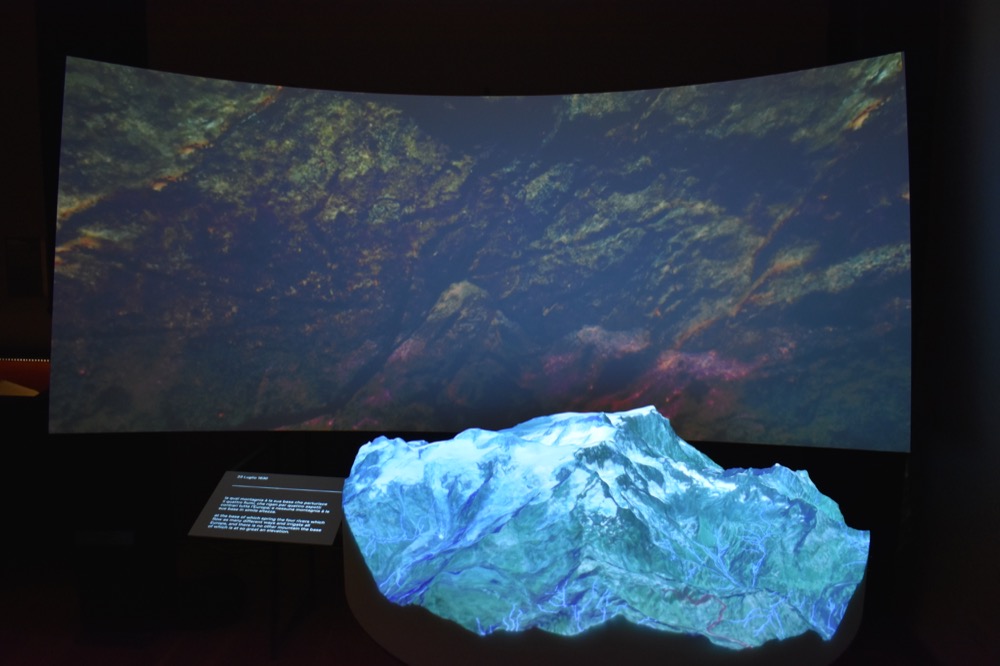

- Based on my own experience, the exhibition is very well-oriented and not crowded (because the organiser controls the people flow), which allows visitors to admire the masterpieces at their own pace. The models and multi-media devices installed for the show give deep insights into the genius mind and vision of the great master.

2. Practical information

2.1 Opening hours

- The exhibition will be held from 16th April to 14th July 2019.

- From Monday to Sunday: 9:00 – 19:00

- The last entry is at 18:00.

2.2 Ticket prices

Admission ticket for the exhibition alone:

- Full price ticket: € 15.00

- Reduced price ticket (young people between 18 and 25 years old, old people above 65 years old, holders of the Royal Museums of Turin ticket, etc.): € 10.00

- Reduced price ticket (children between 6 and 14 years old, etc.): € 5.00

- Free admission: children under 6 years old, holders of Torino + Piemonte Card or Royal Card, etc.

- For more information about discounted or free admission please click here.

Combined ticket (admission to the Royal Museums of Turin and to the exhibition):

- Full price ticket: € 20.00

- Reduced price ticket (young people between 18 and 25 years old): € 10.00

- Reduced price ticket (children between 6 and 17 years old): € 8.00

It is possible to book individual tickets online and it’s required to reserve group tickets through phone or email. I arrived at the ticket office at around 9:00 when it was just open and there was almost no line. After purchasing the combined ticket, I went straight to the Leonardo exhibition and again there was no line and only a few visitors. After my visit (at around 10:30 on Saturday), there was a short line in front of the exhibition entrance and a rather long line in front of the ticket office already.

2.3 Other important information and some tips

- I recommend buying the combined ticket because both the exhibition and the Royal Palace Complex of Turin are worth visiting. The latter is a historic palace of the House of Savoy originally built in the 16th century and a UNESCO World Heritage site.

- I recommend arriving early in the morning to avoid standing in line because both the exhibition and the palace complex are very popular among tourists. (Just get there when the ticket office opens. I don’t think it’s necessary to arrive much earlier.)

- The exhibition is very well-organised. Just follow the signs on the walls and you will see everything.

- The installation of models based on Leonardo’s studies and the employment of multi-media devices give the exhibition a modern touch.

- Detailed explanations (both in Italian and English) are shown on the info boards on the walls.

- Photography for personal use is allowed in the exhibition but strictly without flash. Please be considerate while taking photos both for the preservation of these precious works and for the convenience of other visitors.

- In my opinion, you should spend about 1.5 hours in the exhibition learning about Leonardo’s fabulous works and achievements. After that, visit the Royal Palace Complex of Turin including the Royal Palace, Royal Garden, Royal Armoury, Royal Library, Sabauda Gallery, Archaeological Museum, and the Holy Shroud Chapel. The complex is huge and it will probably take you a whole day or even more to see everything.

3. Highlights

The exhibition focuses on the thirteen autograph drawings by Leonardo da Vinci and his “Codex on the Flight of Birds” preserved in the Royal Library of Turin. It is divided into six sections, which respectively talk about the heritage of ancient art, the exploration of anatomy and proportions of the human body, the interaction between art and poetry, self-portrait, the study of faces and challenge of portraying emotions, and the studies of flight and architecture. The last section also deals with a relatively unexplored theme, that is to say, the relationship between Leonardo and Piedmont, as well as a selection of texts in his library.

In the following paragraphs I’ll show you the works that impressed me the most in the exhibition.

3.1 The heritage of ancient art

3.1.1 Designs for Scythed Chariots (ca. 1485)

Upon entering the first exhibition room, I was immediately drawn towards Leonardo’s designs for scythed chariots. I guess except the master, not many artists’ sketches can be admired as fantastic artworks themselves. The two assault chariots, fitted with terrifying rotating scythes that could cut open a path through energy lines, are a type of war machine that had been used in antiquity and that Leonardo knew about from the military treatise written by the humanist Roberto Valturio. In addition to his attention to the mechanical details, which real his technical and design skills, we also see Leonardo’s artistic sensitivity, for he accentuates the visionary and dramatic power of the composition by depicting the impetuous horses and riders and the macabre details of the dead soldiers surrounded by bits of hacked limbs.

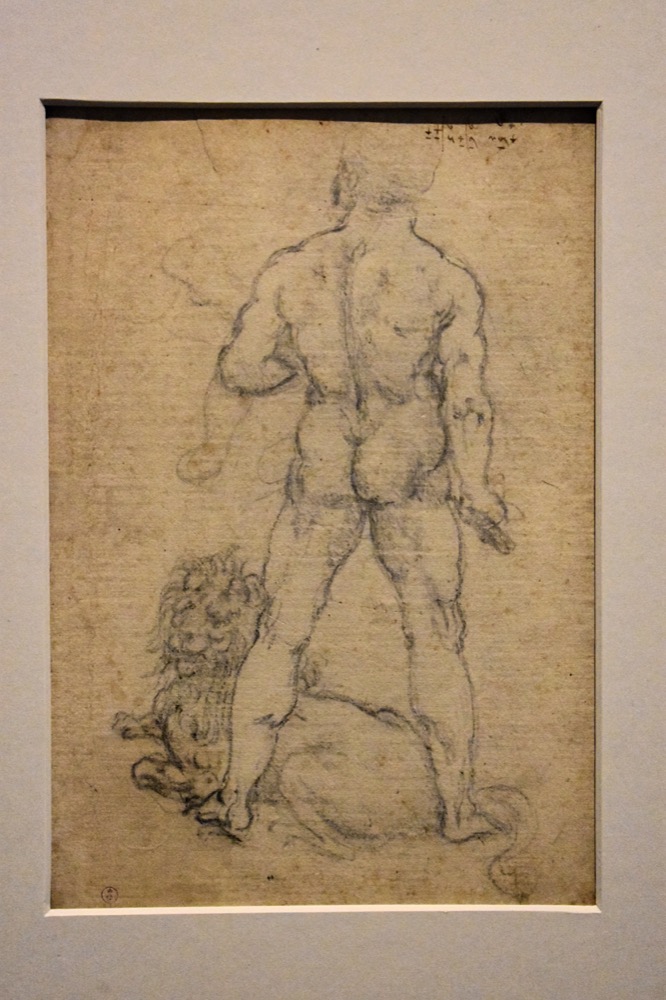

3.1.2 Hercules with the Nemean Lion (ca. 1505 – 1508)

The drawing shows Hercules from behind, with a club in his hands and the Nemean lion crouching meekly at his feet, a vicious monster in Greek mythology that could not be killed with mortals’ weapons because its golden fur was impervious to attack. This was probably a design for a statue, which was never made, to be placed next to Michelangelo’s David in front of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, where Baccio Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus group was later placed, recalling the model by Leonardo. The rapid and softened chiaroscuro of the muscles tackles the problem, which was common among Renaissance artists, of rendering reliefs on a flat surface.

3.1.3 Male Head in Profile with Laurel Wreath (ca. 1506 – 1510)

With his head in profile crowned with laurel leaves, a proud expression and a solemn bearing, but also a detailed depiction of the facial features, the figure combines an idealised heroic type of classical inspiration with a realistic portrait. Similar to some other drawings made in his youth, here Leonardo emphasises the celebratory nature of the figure.

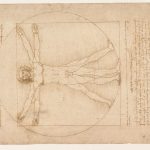

3.2 The exploration of anatomy and proportions of the human body

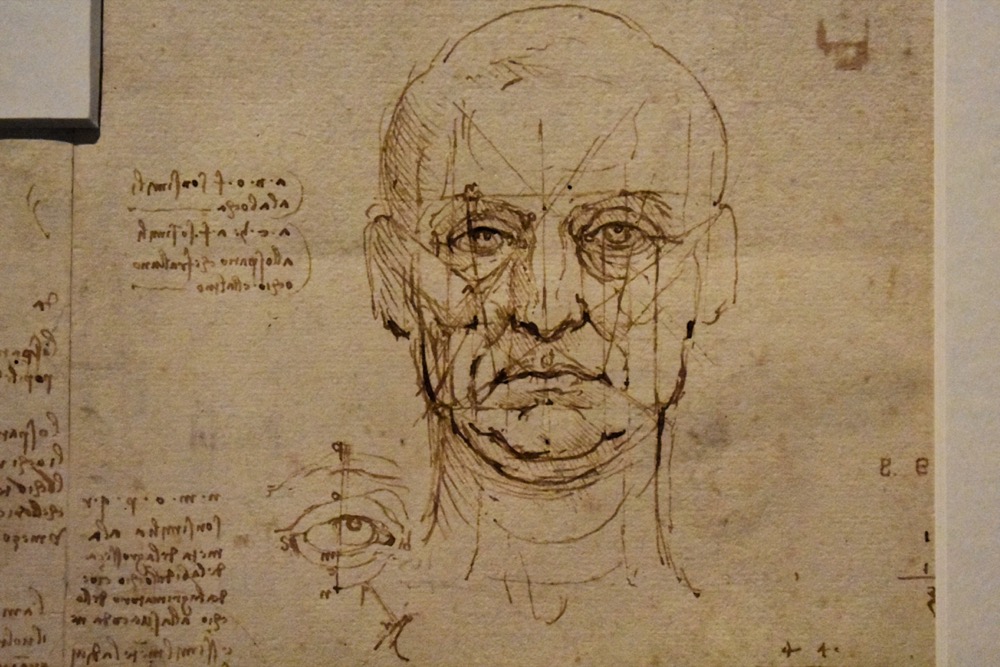

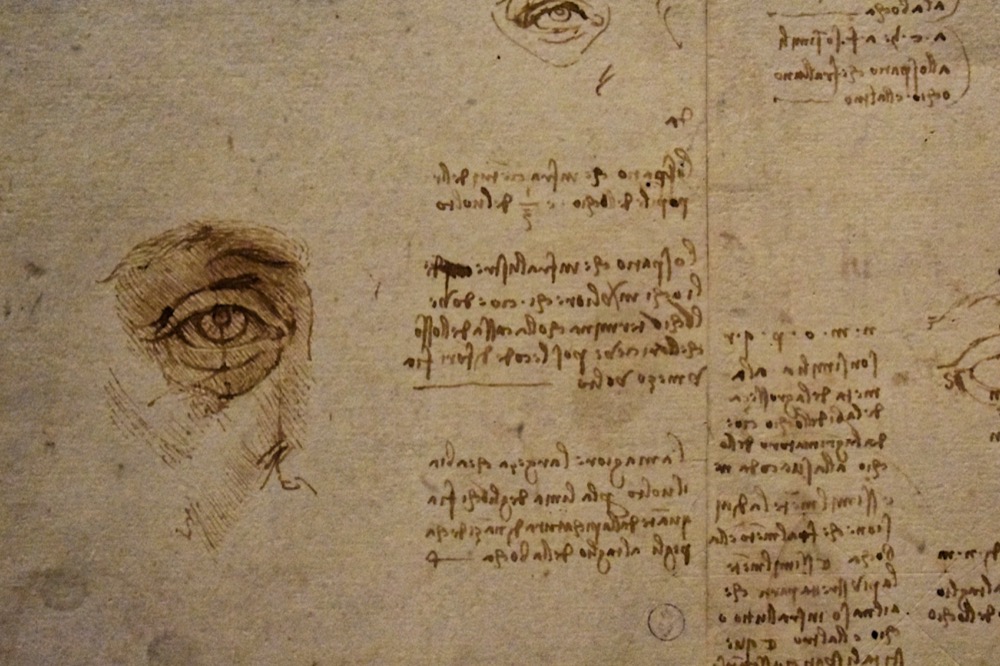

3.2.1 Studies of Human Face and Eye

During the Renaissance, the representation of human body and its proportions became a particularly popular subject of study among artists. The observation and analysis of human anatomy started in the studio, where young apprentices would refine their skills in depicting static models. Leonardo too certainly practised this in Verrocchio’s studio, but during the course of his life, he devoted himself to more in-depth studies of the internal organs and their functions, finding ways to render the movement and expressiveness of the body.

The drawing, which consists of two joined sheets, is clear evidence of the formidable studies of human body and its proportions carried out by Leonardo in about 1490. The sheet on the right (1st picture above) gives measurements and proportions of the human face while the one on the left (2nd picture above) examines proportions of the eye. It also shows Leonardo’s interest in reflecting on nature and man in order to pick out universally valid descriptive rules by means of the sense of sight, which he considered as the primary instrument of pursuing all knowledge.

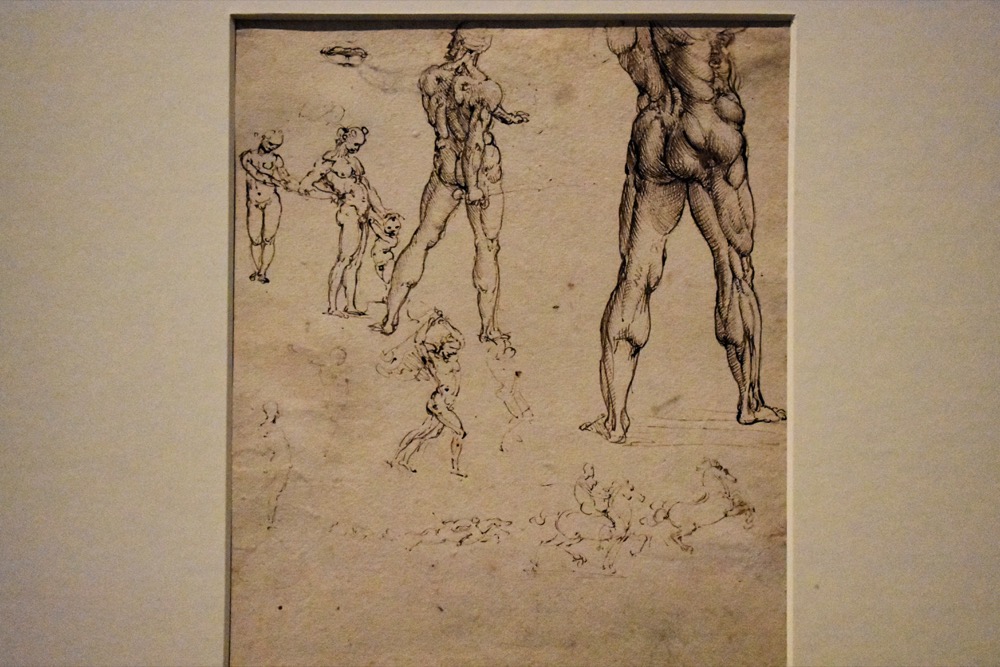

3.2.2 Study for The Battle of Anghiari

The “Battle of Anghiari” is a lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci, which some commentators believe to be still hidden beneath one of the later frescoes in the Salone dei Cinquecento (Hall of the Five Hundred) in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Its central scene depicted four men riding raging war horses engaged in a battle for possession of a standard, at the Battle of Anghiari in 1440. The composition of the central section is best known through a drawing by Peter Paul Rubens in the Louvre, Paris. This work, dating from 1603 and known as “The Battle of the Standard”, is based on an engraving of 1553 by Lorenzo Zacchia, which was taken from the painting itself or possibly derived from a cartoon by Leonardo. Rubens succeeded in portraying the fury, the intense emotions and the sense of power that were presumably present in the original painting. Similarities have been noted between this “Battle of Anghiari” and the “Hippopotamus Hunt” painted by Rubens in 1616, which is exhibited in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

The drawing shown above contains some preparatory sketches for the Battle cartoon, together with some figure studies in the background on the left. Here we see clearly Leonardo’s investigation of moving nude bodies, from which similar studies by Raphael and Michelangelo took inspiration. In the lower part of the drawing we see three studies of horses and riders captured with concise expressiveness.

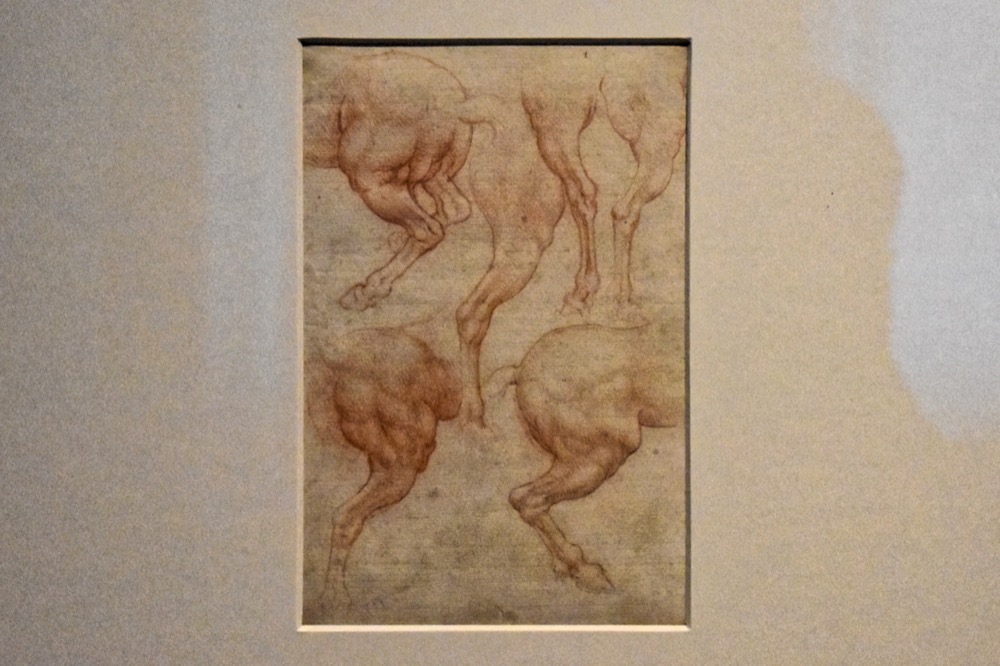

3.2.3 Study of Horses

One of the most famous studies by Leonardo is that of horses, on which he spent much of his time both for the design of equestrian monuments and for his paintings. In this exhibition, I saw a few sheets related to this theme.

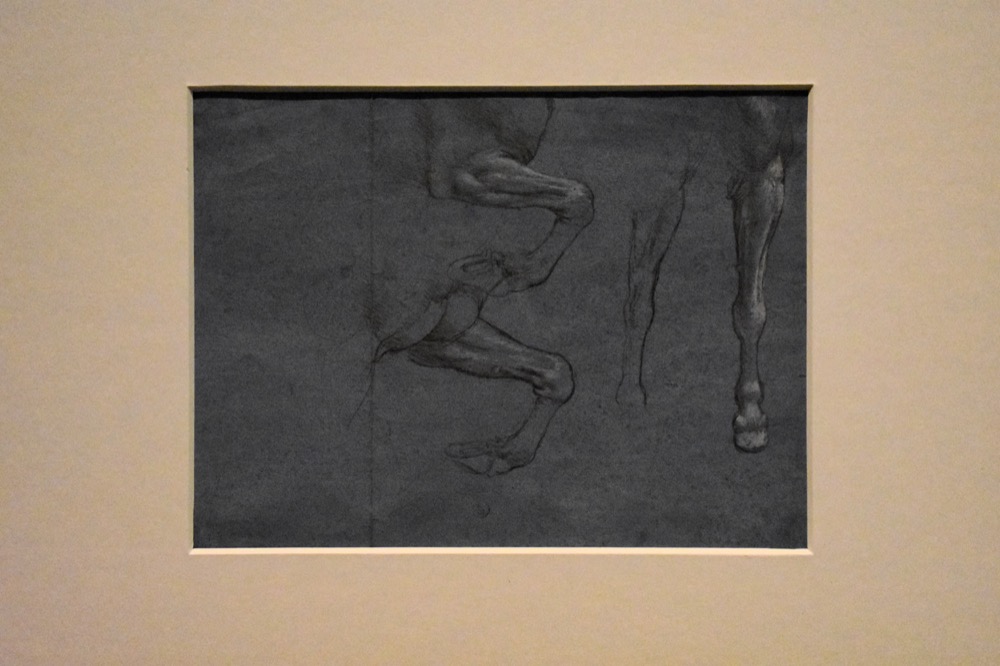

Study of the Forelegs of a Walking Horse

This study shows the forelegs of a walking horse, with one limb raised and bent and the other taking the weight. It probably dates from the time when Leonardo was working on the second version of the monument to Francesco Sforza. Here he is no longer focusing on the study of movement, as in the first version, but closer to the models of classical statuary. To broaden his knowledge of classical art, he went in 1490 with Francesco di Giorgio Martini to Pavia, where he was able to admire the equestrian statue known as the Regisole, a work from Late Antiquity that was destroyed in the late 18th century.

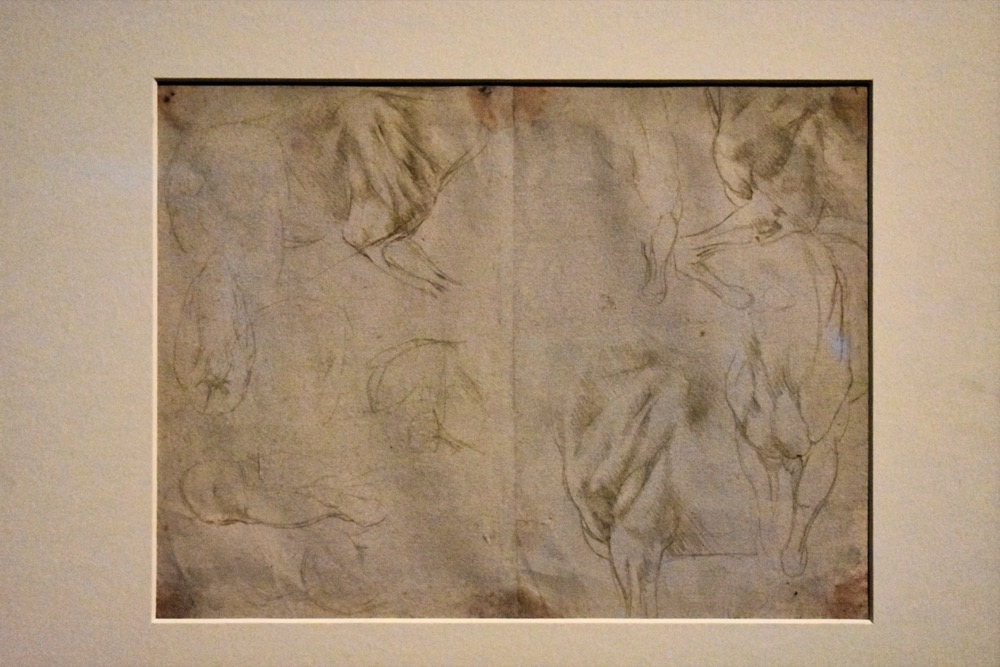

Study of the Forelegs of a Horse

This double folio contains a series of sketches in which, with some parts clearly defined by chiaroscuro while others barely sketched in, the structure of the front legs is shown in various positions and the pectoral muscles are seen from the side and front.

Study of Horses

This folio contains six sketches: the hooves are outlined in a mirror image at the top right; the rear part of a torso is shown at the top left with a tail sketched in; in the centre is another leg with chiaroscuro hatching; and at the bottom we see a set of limbs. The powerful musculature where the legs join the rear part of the body is described in detail, with the use of different degrees of chiaroscuro. The drawing is most likely done by Leonardo himself, but it’s also quite possible that Francesco Melzi, one of the master’s pupils and assistants, had a hand in it.

3.2.4 Rearing Horse and Mounted Warrior (permanent exhibit of the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts)

Last year during Easter I visited Budapest, but unfortunately the Museum of Fines Arts was under reconstruction and was closed to the public. One of the exhibits that I wanted to see the most there was the Rearing Horse and Mounted Warrior, which is attributed to Leonardo da Vinci because stylistically it’s very similar to the drawings that he made during the last years of his life in France. Surprisingly I saw it in the temporary exhibition in Turin, which was like destiny. I have seen many of Leonardo’s drawings and paintings, but this was the first time I saw his statue.

In 1516, after invitations from King Francis I of France and his predecessor, Louis XII of France, Leonardo moved to France and entered the service of Francis I. Art chronicler Gian Paolo Lomazzo, close to Leonardo’s heirs, wrote in 1584 that Leonardo had made several models of horses for Francis. This statuette is believed to be one of them. The attribution has been widely accepted, more seriously than other sculpture attributions to Leonardo, and according to art historian Martin Kemp, is well supported. There is, however, some doubt, especially on the rider. Hungarian art historian Mária Aggházy noticed a resemblance between the content-looking rider and the young Francis I of France, soon to be king, and Leonardo’s patron from his later years.

3.3 The interaction between art and poetry

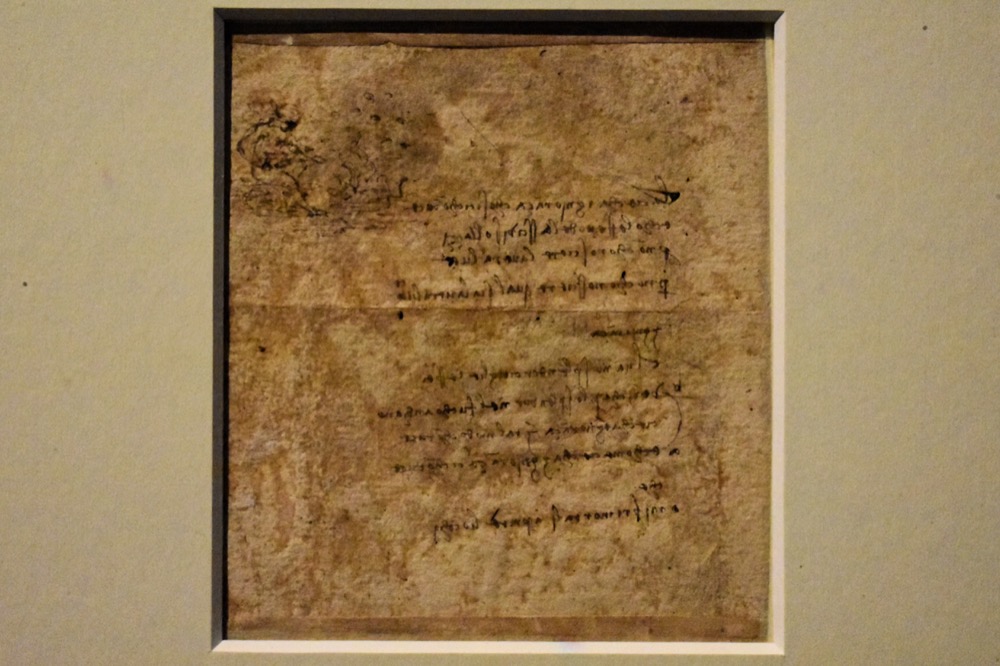

3.3.1 Figure by a Fire and Flying Butterflies, with Poetic Comment (verso), Studies of Leg Muscles (recto) (1483 – 1485)

We know that Leonardo da Vinci was a polymath of the Renaissance whose areas of interest included drawing, painting, sculpting, architecture, science, music, mathematics, engineering, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, history and so on, but do you know he was also a man of letters? On the back of an anatomy study, a short poem and a little drawing illustrate the proverbial analogy between those who burn with vain desire and moths that die in the fire, unaware of the danger and unable to resist the attraction of the light. This and other metaphors with moral value inspired by the world of nature were later developed in fables that Leonardo wrote when he was in Milan at the end of the 15th century. The verses are written in Leonardo’s characteristic mirror-image script. The poem is unfinished, with some verses incomplete or replicated with slight variations.

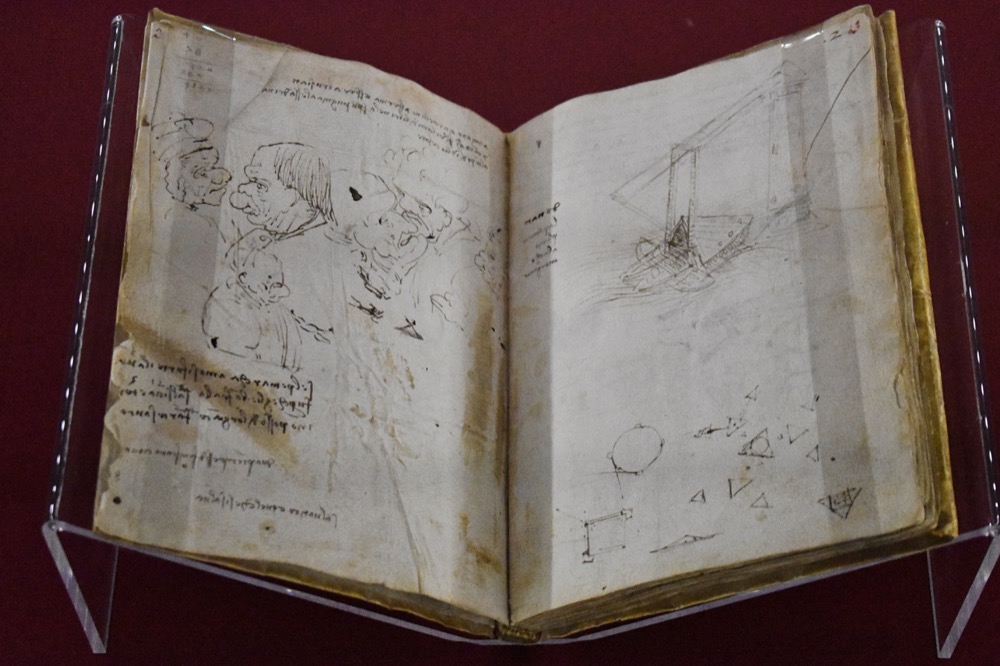

3.3.2 “Codex Trivulzianus” (last quarter of the 15th century) (permanent collection of the Archivio Storico Civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana in Milan)

The notebook used by Leonardo da Vinci during his first stay in Milan contains sketches and studies on a whole range of subjects, alternating with long lists of words. In his childhood, he received an informal education in Latin, geometry and mathematics. The lists point to the artist’s effort to enrich his vocabulary by memorising terms derived from Latin, which were used in scientific and humanistic texts at the time.

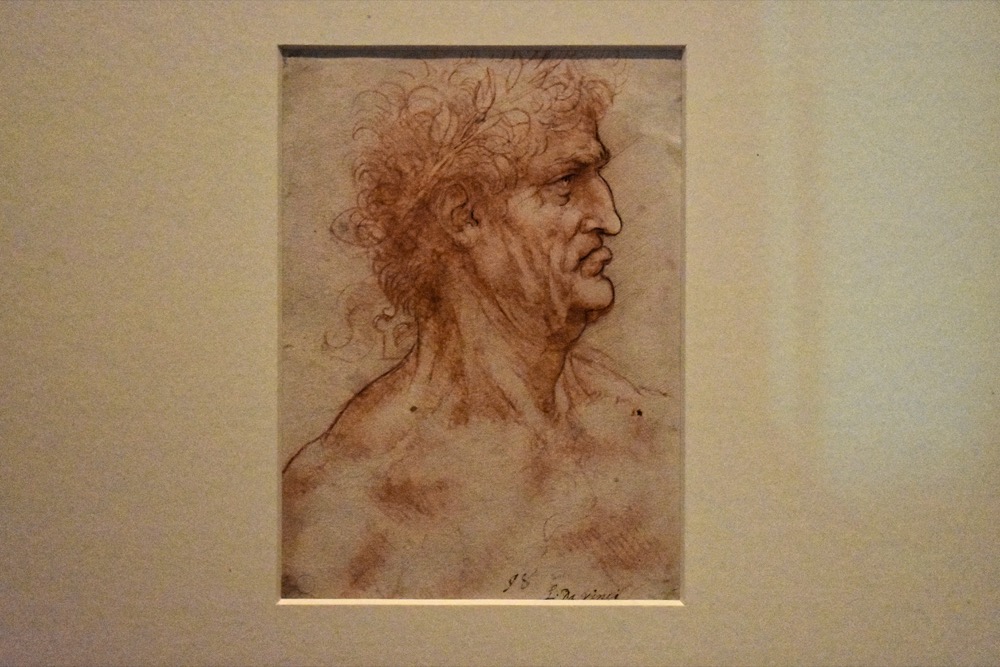

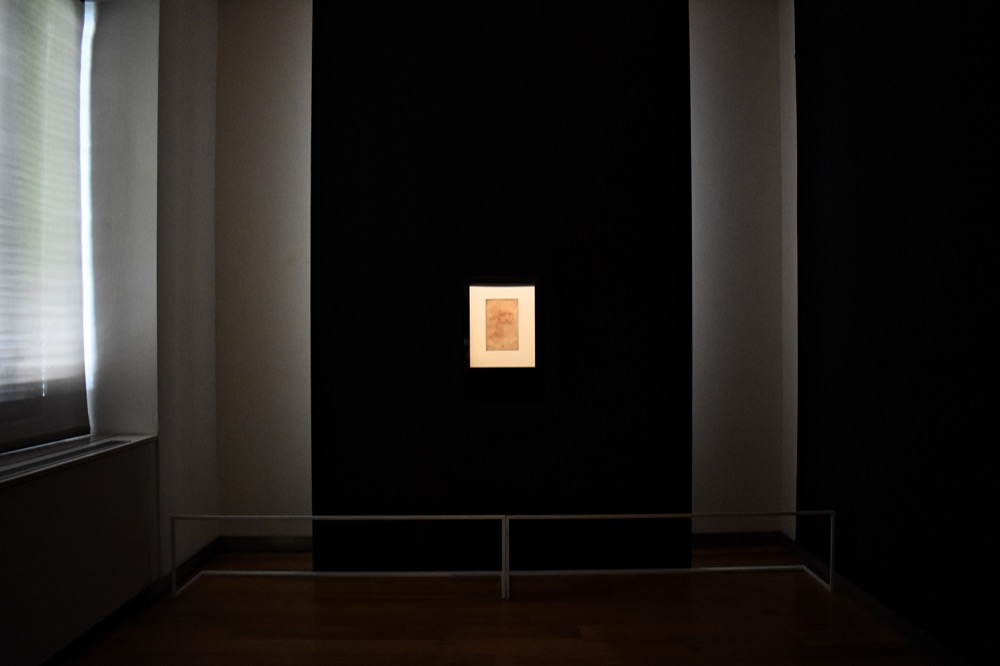

3.4 The Portrait of a Man in Red Chalk

The so-called Self-Portrait of Leonardo is certainly one of the protagonists of the exhibition. I still remember about 1.5 years ago I wrote the Royal Museums of Turin and was really disappointed when they informed me that though the famous Self-Portrait and “Codex on the Flight of Birds” are among the permanent collection of the Royal Library of Turin, like most other drawings, they are rarely shown to the public for preservations reasons. I was traveling in Greece when I heard that the drawings I wanted to see would be displayed from 16th April to 14th July 2019 accompanied by some other masterpieces such as Rearing Horse and Mounted Warrior, which is a permanent exhibit of the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts, Head of a Girl (Study for the Virgin of the Rocks), and “Codex Atlanticus” f. 844r, Details of a Mechanical Wing which comes from the Ambrosian Library in Milan, and I booked tickets immediately. At that moment I understood why some people would travel to a faraway city and spend much money on a ticket just to attend someone’s concert. For me, Leonardo da Vinci is the superstar.

As you can see in the 1st picture above, the drawing is set against a black background, which makes it more outstanding. Compared to most other drawings, it is neither big nor small, but average-sized. I don’t want to but have to admit that the drawing is indeed in rather poor condition as if you don’t take a close look, the facial features, beard and hair are not really clearly visible. I believe most of the pictures of the portrait on the internet have been processed to make the lines more noticeable.

Now let’s see how this drawing became an icon of the Italian Renaissance. Drawn in red chalk on paper and in fine unique lines, the portrait is shadowed by hatching and executed with the left hand, as was Leonardo’s habit. “It never ceases to amaze us with its evocative power, the concentration of the gaze, the bitter and disdainful crease of the mouth, and the brilliant economy of lines that form the wrinkles on a face that emerges with sculptural force almost as if from nothing, surrounded by a cloud of beard and long wavy hair.” The eyes of the figure do not engage the viewer but gaze ahead, veiled by the long eyebrows, with a sense of solemnity. These features coincide with what the sources tell us of Leonardo’s physical appearance: “He had long hair, and such long eyelashes and beard that he seemed to embody the true nobility of learning, like the druid Hermes and ancient Prometheus did in the past” (Giovan Paolo Lomazzo, 1590).

The drawing is widely, though not universally, accepted as a self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci. The assumption was made in the 19th century, based on the similarity of the sitter to the portrait of Leonardo in Raphael’s The School of Athens and on the high quality of the drawing, consistent with others by Leonardo. It was also assumed to be a self-portrait based on its likeness to the frontispiece portrait of Leonardo in Vasari’s Second Edition of “The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects”. Frank Zöllner states: “This red chalk drawing has largely determined our idea of Leonardo’s appearance for it was long taken to be his only authentic self-portrait.” Nevertheless, some historians and scholars disagree as to the true identity of the sitter. Many consider that Leonardo drew this self-portrait at the age of about 60, while others maintain that it is a work from between 1490 and 1495 (when Leonardo was only between 38 and 43 years old), and it depicts a man of a greater age than Leonardo himself achieved, as he died at the age of 67. It has been suggested that the sitter represents Leonardo’s father Piero da Vinci or his uncle Francesco, based on the fact they both had a long life and lived until the age of 80. Another theory suggests that the drawing maybe the head of a philosopher – possibly Aristotle or Heraclitus, one of the great pre-Socrates thinkers. We won’t know for sure who the figure really is but the portrait has been extensively reproduced and has become an iconic representation of Leonardo as a polymath or “Renaissance Man”.

I love what the exhibition says about the drawing, and now I’ll end this section with it.

The ambiguity and fascination of this drawing is in the complexity of Leonardo’s thoughts and possibly also in the elusive discourse of all artists of all ages with regard to themselves: a declaration of how, at a given moment, the artist sees himself and the projection of his dreams, his poetic vision, and his ambitions.

3.5 The study of faces and challenge of portraying emotions

I’m quite sure you’ve heard of Leonardo’s Last Supper. On the UNESCO website, it is said this masterpiece was painted between 1495 and 1497 while according to the convent, where the painting is located, it was executed between 1494 and 1498. No matter how long it took to finish the painting, da Vinci had began his preparation long before the first brush. One of the reasons why it became so famous is that this is a work of the master’s deep thoughts and keen observations of people’s facial expressions, very likely involving the study of psychology. Different from other artists who had painted this theme, focusing on the identification of the betrayer Judas, da Vinci chose to emphasise the moment shortly after Jesus said “Truly I tell you, one of you will betray me”. (For a detailed introduction to the fresco, please click here.)

Leonardo devotes ample space to the representation of face in his drawings and his “Treatise on Painting”. As he sees it, by means of a portrait, the artist must reveal beauty, in the sense of grace and gentleness – qualities that are expressed through the study of physiognomy, and the treatment of light, which strikes surfaces and then softens in delicate chiaroscuro transitions. The artist also needs to respect the infinite variety of nature, avoiding repetition and differentiating faces by age, character and expression. The rendering of facial features has to deal with constant and complex changes brought about by moods, and this is achieved by constant exercise from life and the creation of a vast repertoire of facial types.

3.5.1 Head of a Girl (Study for The Virgin of the Rocks)

As I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, except Leonardo da Vinci, not many artists’ sketches or studies can be regarded as masterpieces themselves. In the permanent collection of autograph works by Leonardo in the Royal Library of Turin, I found three pieces particularly amazing: one is the Portrait of a Man in Red Chalk which I mentioned above, one is the Head of a Girl which I will talk about in this section, and the last one is the “Codex on the Flight of Birds”. Luckily, in this exhibition, I saw all of them.

The position of the bust and gentle rotation of the head mean that this delicate face, which Leonardo manages to capture in just a few lines with light and vibrant chiaroscuro, can be referred to the angel in the first version of The Virgin of the Rocks, now exhibited in the Louvre in Paris. This drawing is one of the finest ever achieved by the artist in terms of its psychological insight and the life we see in the sitter. Leonardo’s technical brilliance can be seen in the spontaneity of the pose and in the liveliness of the young woman’s gaze, which is barely veiled by her slightly lowered eyelids as she looks straight out at the viewer.

3.5.2 Busts of an Old and a Young Man, with Heads in Profile (ca. 1495) (permanent collection of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence)

The comparison between old and young faces is a recurrent theme in Leonardo’s studies. The two figures, which are shown facing each other, represent the contrast between the beauty of youth and deformity of old age: the young man has soft, harmonious features and thick curly hair, while the old man is completely bald with a protruding chin, a bent nose, and toothless jaws. The use of red chalk is extraordinary, alternating extremely fine lines with more pronounced dense traces that form the areas of shadow, as in the superb rendering of the old man’s neck, with its sagging skin furrowed by wrinkles.

The identity of the two sitters in the famous Uffizi drawing caused a heated discussion among art historians, artists and art lovers. Some people who believe Leonardo was homosexual state that the old man is Leonardo himself while the youth is most likely Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, better known as Salaì, an Italian artist and pupil of Leonardo da Vinci from 1490 to 1518. Based on some drawings done by the master, Salaì is believed to be his lover. However, there’s no historical record confirming the assumption.

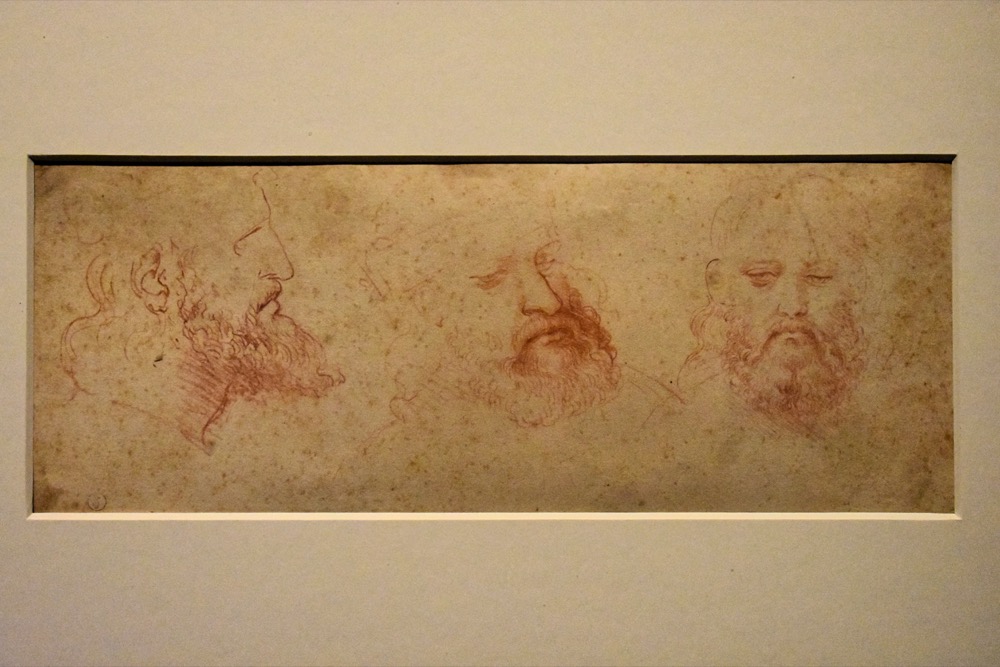

3.5.3 Three Views of the Head of a Man with a Beard (ca.1502)

The folio contains three studies from life of a male face with a long wavy beard and wavy hair falling on his shoulders. The head is shown from the front, in three-quarter view, and in profile – the three typical views of pictorial representation which were also used in preparatory drawings for sculptures. In the past, the man was identified as the famous condottiere Cesare Borgia, but he is more likely to just be some stranger whose face intrigued Leonardo, leading him to put it down on paper. In his biography, Vasari tells us that this was a habit of the master.

3.6 Study of flight

Throughout his life, Leonardo devoted himself to the study of flight. During his first stay in Milan (1482 – 1499), he took an interest in the mechanics of flight, attempting to create a flying machine with beating wings that would reproduce the anatomy and physiology of the flight of birds. From 1503, after returning to Florence, he examined gliding flight with the flight paths of birds and their ability to use the force and direction of the wind. He designed simple machines that could take advantage of updrafts and circle in the air like huge birds of prey. Leonardo’s research was obstructed by the limitation on the sources of energy and materials at his disposal, but even today it never fails to amaze and fascinate us for its visionary power and meticulousness.

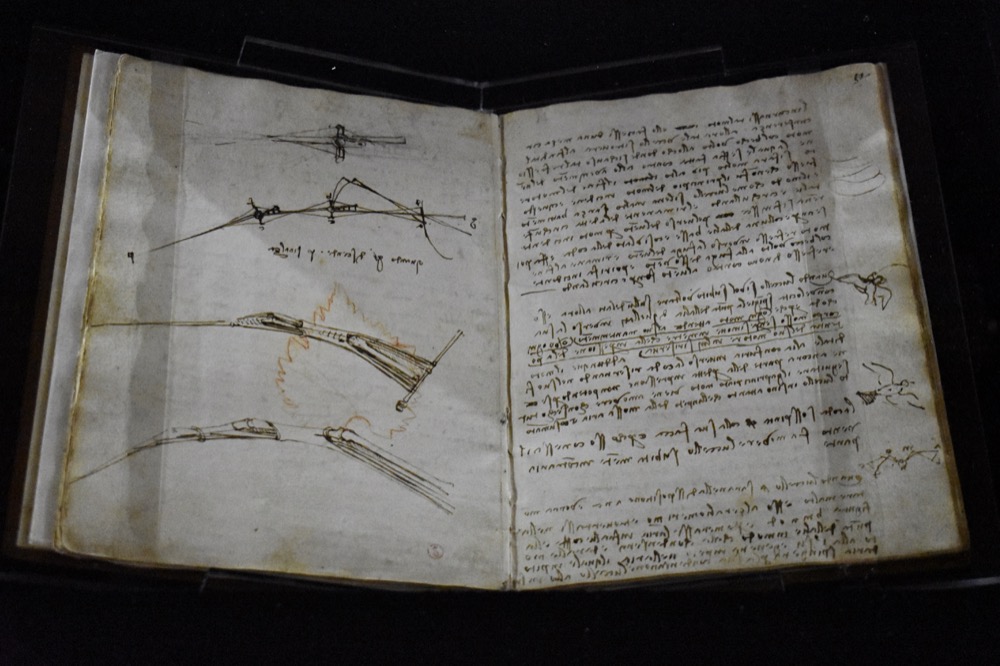

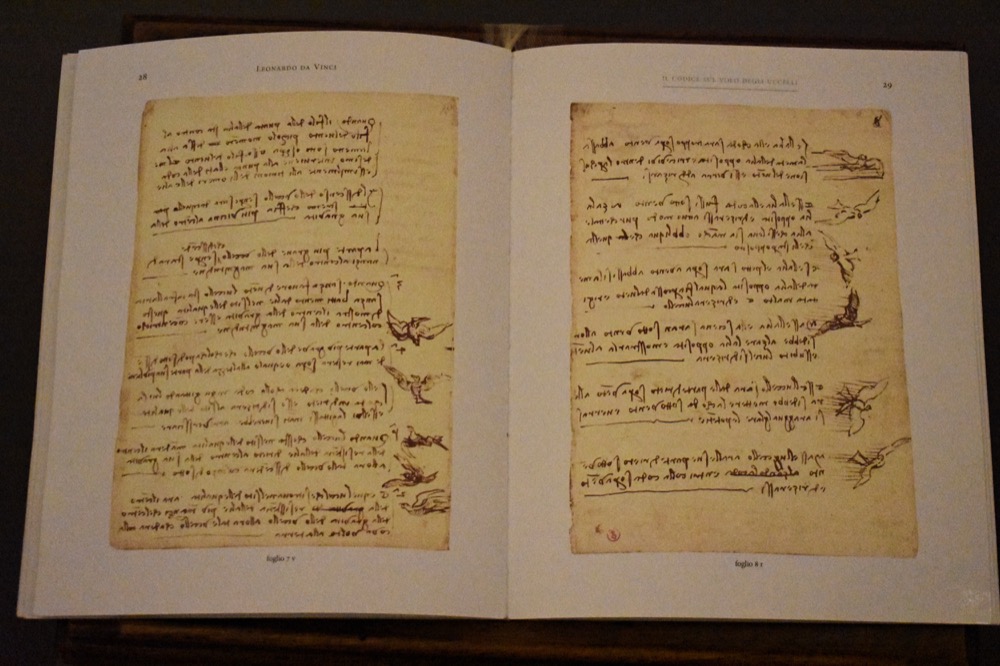

3.6.1 “Codex on the Flight of Birds”

In the exhibition, I was so excited when I saw the entire codex on the flight of birds, not one or two folios but the entire book! The manuscript, which consists of 18 folios, some of which Leonardo had already used, is his most complete set of studies on flight. He intended for it to become the original nucleus of a treatise, but unfortunately never completed it. In his customary mirror-writing, Leonardo noted down his observations and thoughts, accompanying the texts with drawings that describe the flight of birds and his designs for flying machines. The Codex also includes anatomical and architectural drawings and sketches of plants and water courses, testifying to the master’s vast range of interests. Certainly you can’t turn or touch the pages of the original notebook, but next to the display case is a copy of it, in which you can see all the content.

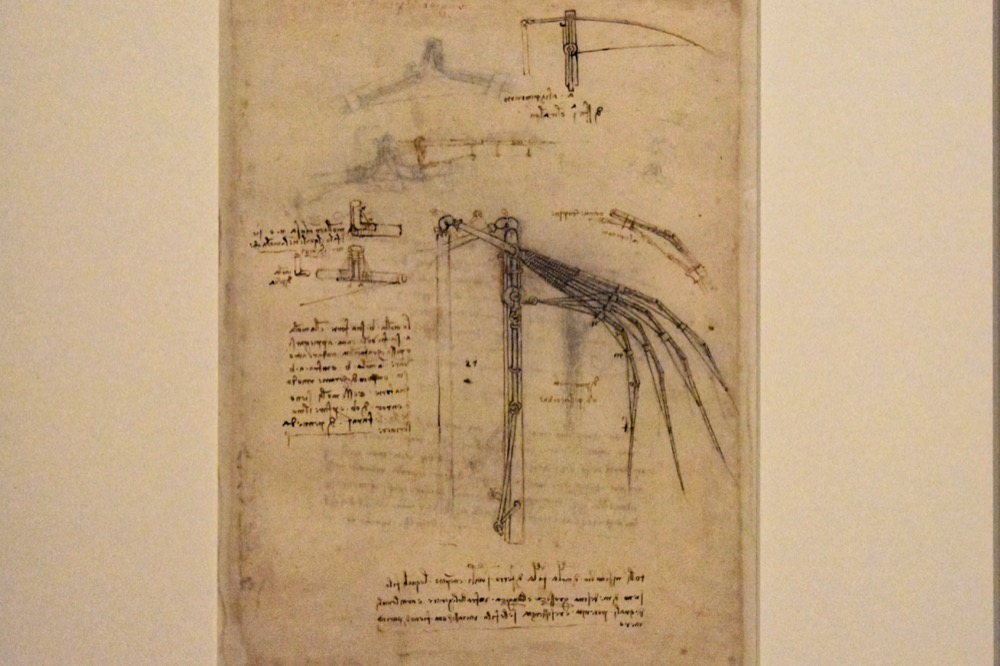

3.6.2 “Codex Atlanticus” f. 844r, Details of a Mechanical Wing (ca. 1493 – 1494) (permanent collection of the Ambrosian Library in Milan)

The “Codex Atlanticus” preserved in the Ambrosian Library in Milan is a twelve-volume, bound set of drawings and writings by Leonardo da Vinci, the largest of such sets. Its name comes from the large paper used to preserve the original da Vinci notebook pages, which was used for atlases. Currently, the Codex comprises 1,119 pages, covering Leonardo’s thoughts for a period of more than 40 years, from 1478 to 1519. With approximately 2,000 drawings and notes, it covers a great variety of subjects including engineering, hydraulics, mathematics, optics, anatomy, architecture, geometry, astronomy, botany, flight, weaponry, musical instruments and so on. If you are interested, please click here to see and learn about the 20 folios I saw in the library in May 2018, which mainly deal with technical, military and architectural themes but also contain many sketches of human figures and animals.

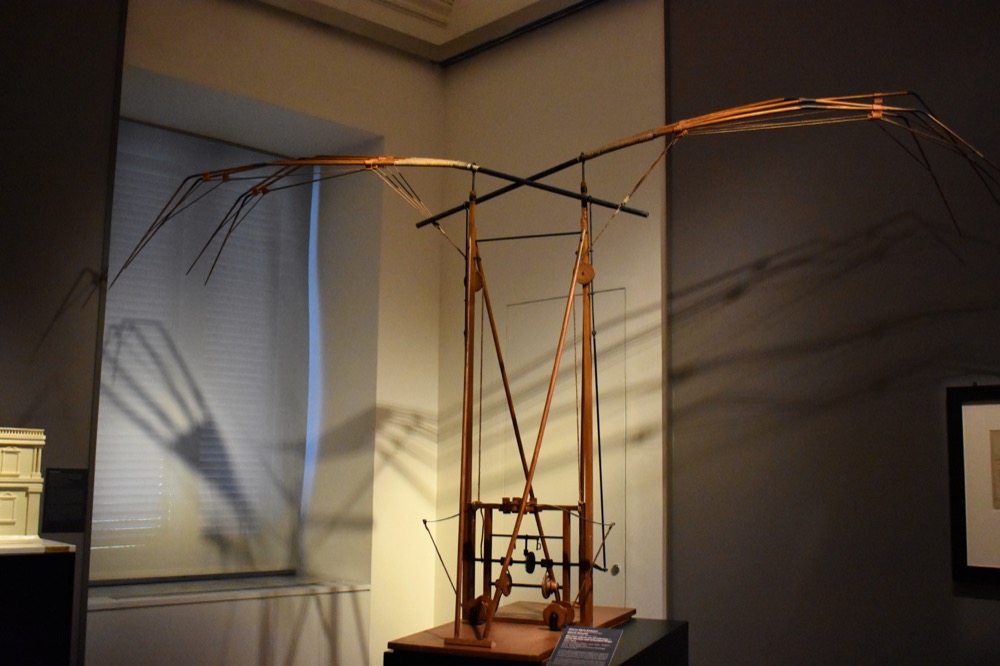

In the folio shown above, which was brought from the Ambrosian Library to Turin for the temporary exhibition, Leonardo studies mechanical structures to imitate the movement of bird wings. By moving the lower rod, the wing is moved up and down and at the same time, the rods that bend the extremities of the wing are pulled by the pulley. The large wooden model of a flying machine with articulated wings on display (as you can see in the 2nd picture above) is inspired by the drawing and is part of a group of works created by the Armed Forces for the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s birth.

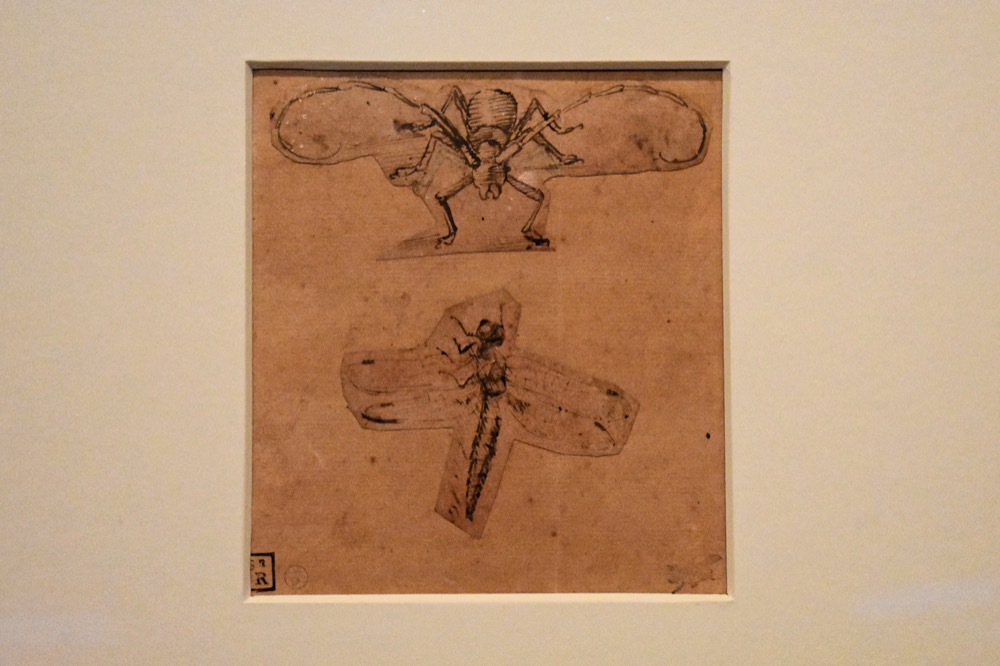

3.6.3 Two Studies of Insects (ca. 1480/ca. 1503 – 1505)

The two studies, drawn on pieces of paper cut out and attached to a sheet of the same colour, represent a great capricorn beetle (above) belonging to the order of the Coleoptera, and a dragonfly (below). Their different graphic treatment – almost horizontal in the first, and more pointy and thin in the second – resulted in their attribution by art historians to two different periods of Leonardo’s career. The extremely high quality of the execution, which can be seen in the exquisite hatching of the veins on the wings and frame of the body, and in the anatomical precision of the legs, clearly shows this is an autograph work by the master himself.

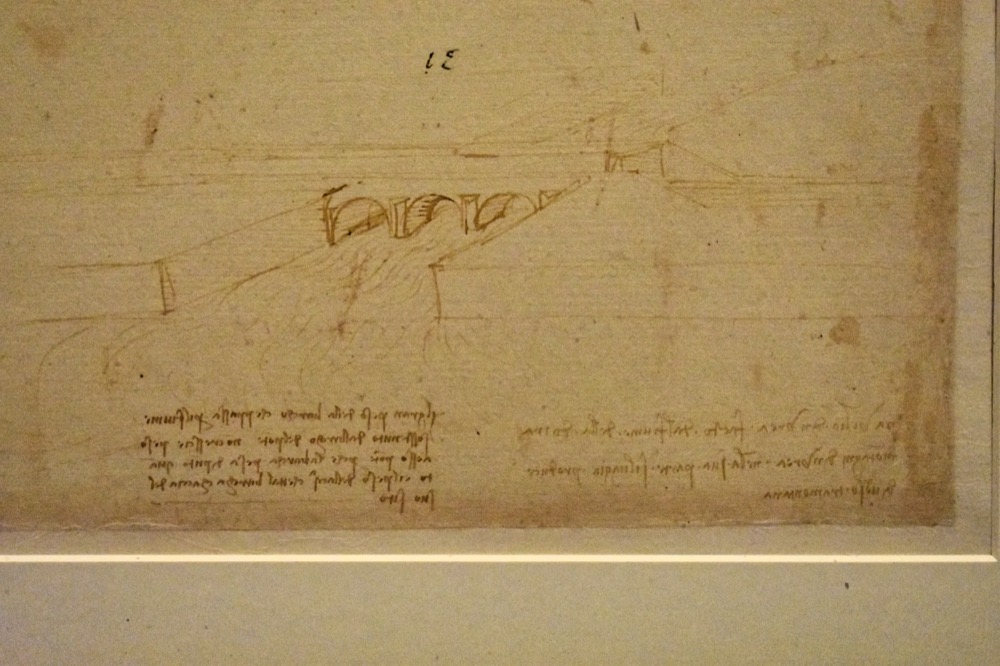

3.6.4 “Codex Atlanticus” f. 563r, Designs and Annotations for a Bridge on the Naviglio d’Ivrea (ca. 1488) (permanent collection of the Ambrosian Library in Milan)

This folio is also part of the “Codex Atlanticus” and it deals with a relatively unexplored theme – the relationship between Leonardo and Piedmont. On it, a bridge over the Naviglio di Ivrea (Ivrea Canal) is depicted, a pioneering feat of hydraulic engineering carried out in the area of Ivrea from 1468 and commissioned by Duchess Jolanda, wife of Amadeus IX of Savoy. Based on texts in the Codex, the Ivrea waterway project is attributed to Leonardo by some historians.

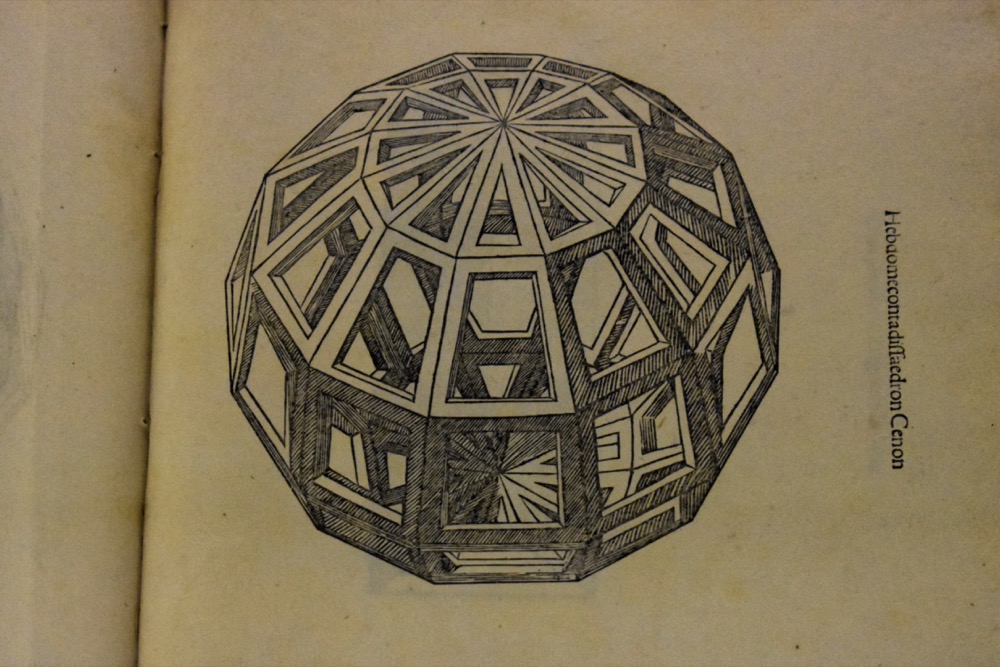

3.6.5 “Divina Proportione” (1509) (Luca Pacioli)

The famous “Divina Proportione”, a book on mathematics, was composed around 1498 in Milan by Luca Pacioli and first printed in 1509 in Venice. Pacioli produced three manuscripts of the treatise by different scribes. He gave the first copy, which is now preserved in the Bibliothèque de Genève in Geneva, to Ludovico il Moro, the Duke of Milan; the second copy, which is now preserved in the Ambrosian Library in Milan, to Galeazzo da Sanseverino; and the third one, which is now missing, to Pier Soderini, the Gonfaloniere of Florence. Leonardo da Vinci, who was a friend of the author, made the drawings of the polyhedra while he lived with and took mathematics lessons from Pacioli, and is referred to with admiration in the text.

[…] and Mounted Warrior is also attributed to Leonardo, which I saw in the temporary exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci. Drawing the Future” in Turin), modelled when he was still a young lad in his master’s […]

[…] and went to Turin immediately. If you didn’t make it to the temporary exhibition, please click here to see the major works shown to the […]