In my previous post, I introduced to you in detail Leonardo da Vinci‘s “Portrait of a Musician“, Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis’ “Lady with a Pearl Hairnet“, and Jan Brueghel the Elder‘s “Vase of Flowers with Jewelry, Coins and Shells“. For the fans of Leonardo, I also talked about Il Vespino‘s copy of the master’s “The Last Supper” and Salaì, whose life story and connection to the master are indeed curious. Moreover, among the huge collection of Cardinal Federico Borromeo, he expressed his particular appreciation of Jacopo Bassano‘s “The Rest on the Flight into Egypt” and Federico Barocci‘s “The Nativity“, which were also introduced in the previous post. In this post, we will finally visit the Ambrosian Library and besides the numerous illuminated manuscripts dating back to Medieval and Renaissance times, we will see a few folios with drawings by Leonardo and his pupils from the famous “Codex Atlanticus“, donated to the library by the Marquis Galeazzo Arconati in 1637. Normally, such drawings, such as Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” in Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and his “Self-portrait” and “Codex on the Flight of Birds” in the Royal Library in Turin, are kept in a special space with controlled humidity and temperature and are not visible to the public, but here in the Ambrosian Library, we have the rare opportunity to see the great master’s own notes and drafts and look into his superhuman mind. Isn’t it exciting? After introducing to you the library and its treasures, we will finish the remaining itinerary of the art gallery in which we will see a few important portraits by Francesco Hayez and a few historical rooms including Room 8 (della Medusa), Room 9 (delle Colonne), Room 12 (dell’Esedra), Room 13 (Nicolò da Bologna) and the Courtyard of the Great Spirits. Now, let’s first take a look at the library’s history and archive and then I will give you a detailed presentation of the exhibited pages of the “Codex Atlanticus”.

Biblioteca Ambrosiana (The Ambrosian Library)

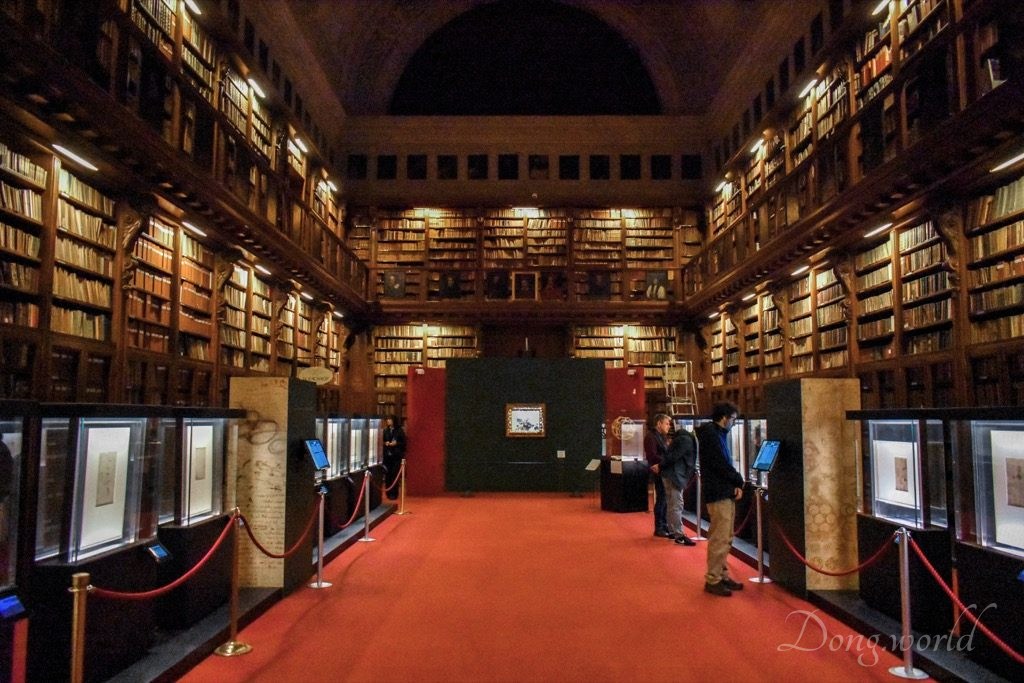

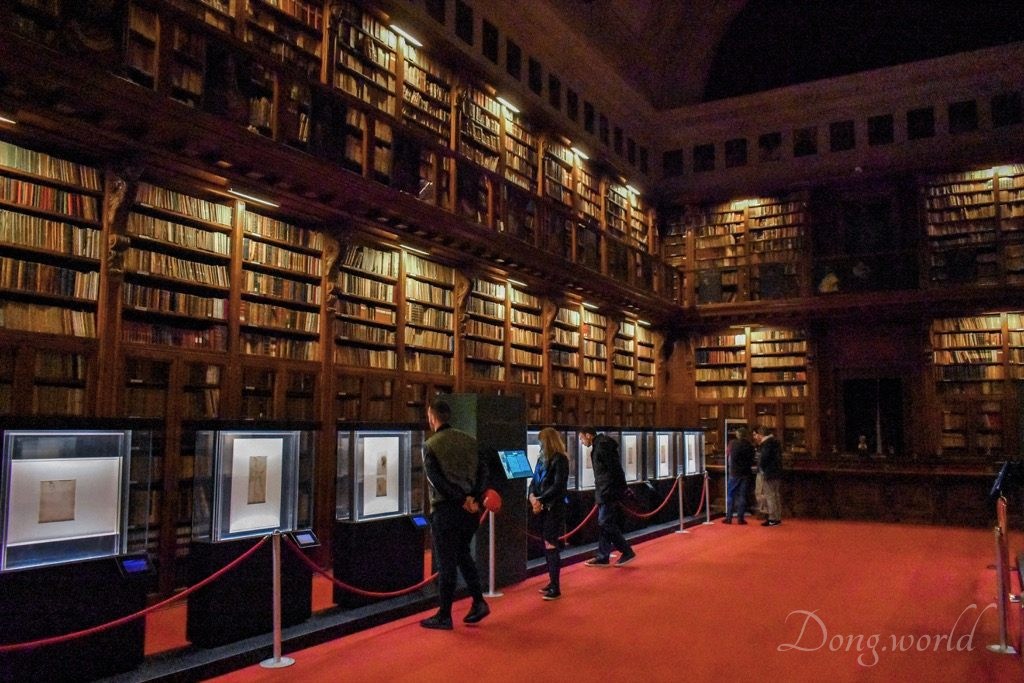

The Ambrosian Library, conceived as a centre for study and culture, was founded by Cardinal Federico Borromeo in 1607 and inaugurated two years later in 1609. The Cardinal named it after the patron saint of Milan, St. Ambrose. After the opening of its first room, the Sala Fredericiana which we will see below, it became the second oldest public library in Europe, after the Bodleian Library in Oxford which was opened in 1602. One innovation done to the library was that the books were stored in cases arranged along the walls rather than chained to the reading tables, a medieval practice still seen in the Laurentian Library of Florence.

Since the library’s foundation, Federico Borromeo’s agents searched Western Europe and even Greece and Syria for books and manuscripts. Nowadays, the Ambrosian Library is undoubtedly one of the most important libraries in Italy and even in the whole world not only because of the huge size of its collections but also because of their unmeasurable values. The library has had illustrious Fellows, Prefects and Doctors including Giuseppe Ripamonti, Ludovico Antonio Muratori, who discovered the Muratorian fragment, the earliest known list of New Testament books, Giuseppe Antonio Sassi, Cardinal Angelo Mai, Antonio Maria Ceriani, Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, who later became Pope Pius XI, the first sovereign of Vatican City from its creation as an independent state on 11th February 1929, and Giovanni Mercati.

Throughout centuries, the library received and welcomed many distinguished guests, which include Galileo Galilei, who wrote that the Ambrosian “library is brave and immortal”. As I read from Ed Quattrocchi’s article “Pietro Bembo – A Renaissance Courtier Who Had His Cake and Ate It Too”, in 1816, Byron visited the library and regarded the letters between Lucrezia Borgia and Pietro Bembo as “the prettiest love letters in the world”. It is also written in the article that when the librarian was out of the room, Byron stole one long strand from Lucrezia’s lock of hair (now exhibited in Room 8),“the prettiest and fairest imaginable.” I do hope that this was just a joke made by Byron himself. Mary Shelley, an English novelist, short story writer, and travel writer and the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley, is also said to have visited the library but her experience was not as pleasant as the previous two visitors because of the tight security resulted from the recent attempted theft of “some of the relics of Francesco Petrarca”.

As I mentioned above, since the library’s foundation, Federico Borromeo’s agents searched Western Europe and even Greece and Syria for books and manuscripts. “These include the precious acquisitions of complete library collections originating from religious institutions such as the Benedictine Monastery of Bobbio, the Augustine Convent of Santa Maria Incoronata and the Library of the Metropolitan Chapter (Capitolo Metropolitano) in Milan, as well as those originating from important private collections such as those of Gian Vincenzo Pinelli, Francesco Ciceri and Cesare Rovida, all renowned scholars and bibliophiles of the XVI century.” (ambrosiana.eu) From then on, various generous donors made great contributions to the enrichment of the library’s collections throughout the centuries.

Nowadays, the library’s collection of drawings, etchings and prints is made up of approximately 40,000 items with around 12,000 drawings by European artists dating from the 14th through the 19th centuries. It also houses around 30,000 manuscripts, which range from Greek, Latin and Italian to Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic, Ethiopian, Turkish and Persian. Besides Leonardo da Vinci’s “Codex Atlanticus“, which I’ll talk about in detail in the next chapter, some of the most precious manuscripts include:

- the “Ambrosian Iliad” or “Ilias Picta“, a 5th-century illuminated manuscript on vellum of the Iliad of Homer. As one of the oldest surviving illustrated manuscripts, it is thought to have been produced in Constantinople either in the late 5th century or early 6th century. As I read from Wikipedia, “it is the only surviving portion of an illustrated copy of Homer from antiquity and, along with the Vergilius Vaticanus and the Vergilius Romanus”, both of which are in the Vatican Library, “one of only three illustrated manuscripts of classical literature to survive from antiquity.”

- codice “Virgil” or “Ambrosian Virgil“, which was illuminated by Simone Martini, Giuseppe Flavio and is in Latin on papyrus with notes on the margins by Francesco Petrarca.

- the “De Prospectiva Pingendi” by Piero della Francesca, the earliest and only pre-1500 Renaissance treatise solely devoted to the subject of perspective.

- the Muratorian fragment, a 7th-century Latin manuscript bound in a 7th- or 8th-century codex and a copy of possibly the oldest known list of most of the books of the New Testament.

- and the famous “De Divina Proportione” codex by Luca Pacioli, which was composed around 1498 in Milan, illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci and first printed in 1509. Pacioli produced three manuscripts of the treatise by different scribes. He gave the first copy, which is now preserved in the Bibliothèque de Genève in Geneva, to Ludovico il Moro, the Duke of Milan; the second copy, which is now preserved in the Ambrosian Library in Milan, to Galeazzo da Sanseverino; and the third one, which is now missing, to Pier Soderini, the Gonfaloniere of Florence.

There’s still a lot to learn about the library’s history, collections and other donors and if you are interested, please click here to read more on the official website. Now, it’s finally time to see the greatest artistic and scientific treasure of all in the library, that is to say, Leonardo’s “Codex Atlanticus”. I admit that although now I’m in love with lots of artworks here, these 20 folios gave me the first motivation to visit the library and gallery. The codex contains 1119 pages but only 20 are exhibited, which is both fortunate and unfortunate. I say it’s fortunate because firstly, as I mentioned above, such drawings are normally kept under special conditions and are unaccessible to the public but here we can see the original ones for real and secondly, we know that most of the pages are kept safely and will be available to our future generations. Nevertheless, unfortunately we can only see 20 out of the 1119 pages. When it comes to Leonardo’s works, how can I not be greedy and not desire to see more? To some extent, seeing the original is more about the feeling and experience because you can find photos of more than 400 pages of the codex on the official website and I’m quite sure you can find photos of all of them on the internet, but photos and actual drawings are after all different and the individual explanation on site to each of the folios is indeed practical and helpful. I heard that the important and interesting pages of the Codex take turns to be exhibited and I hope it’s true. In this case, I’m afraid I’ll need to visit Milan more frequently and probably even apply for a membership card in the future. Now, mostly based on what I learnt from the info boards on site, I’ll give you a general introduction to the “Codex Atlanticus” and talk about the 20 original folios that I saw. Are you ready to be amazed by the “unquenchable curiosity” and “feverishly inventive imagination” (Helen Gardner) of the “Universal Genius“?

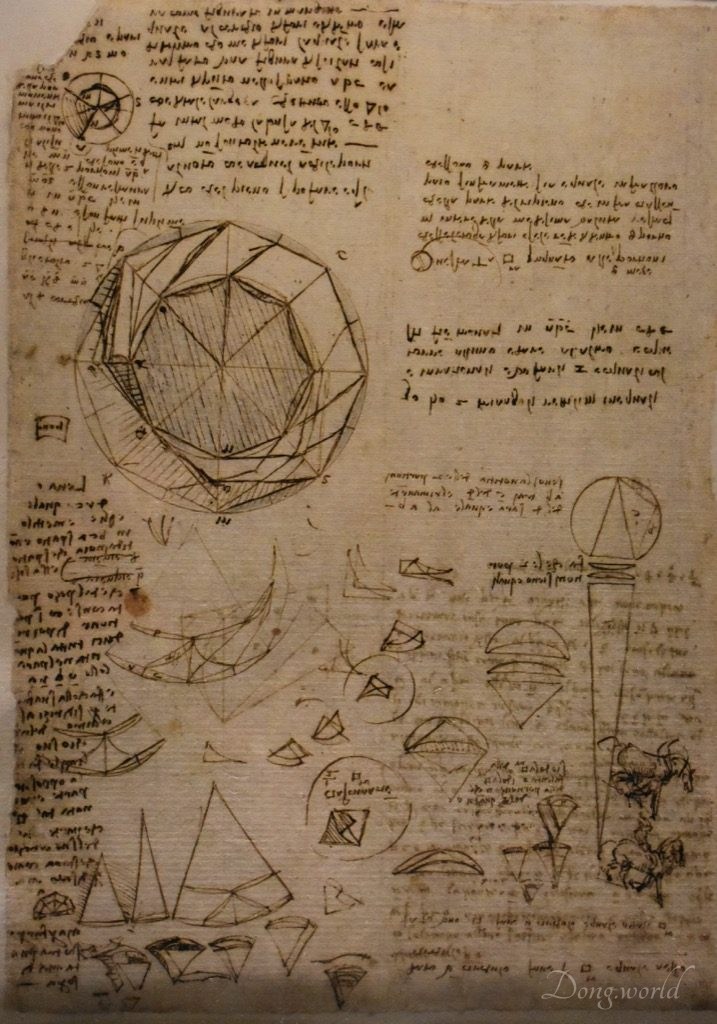

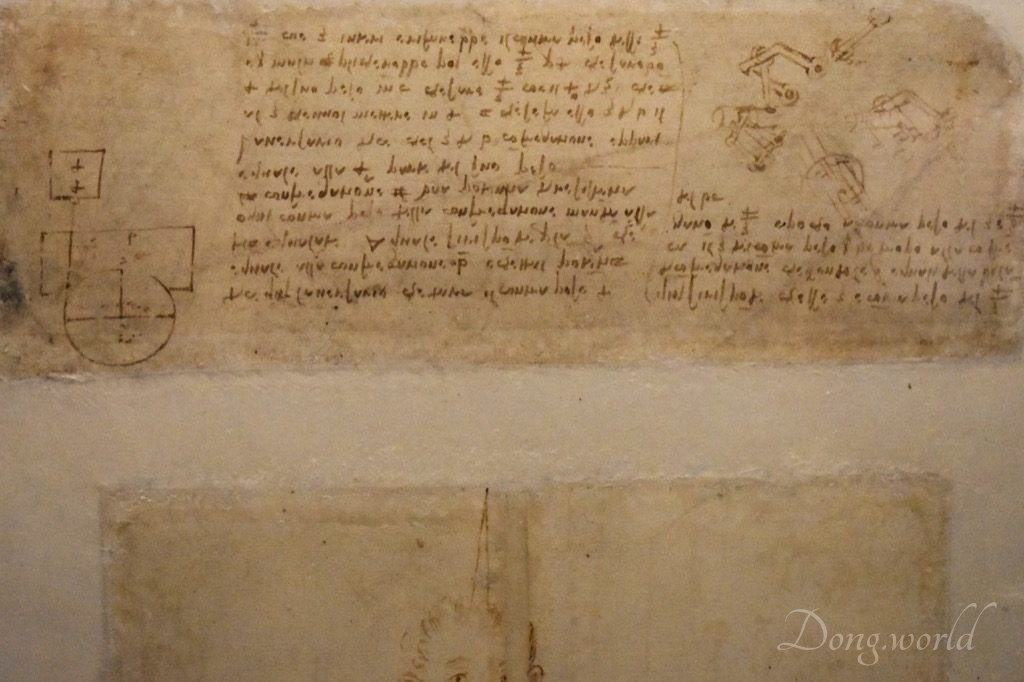

“Codex Atlanticus” by Leonardo da Vinci and his pupils

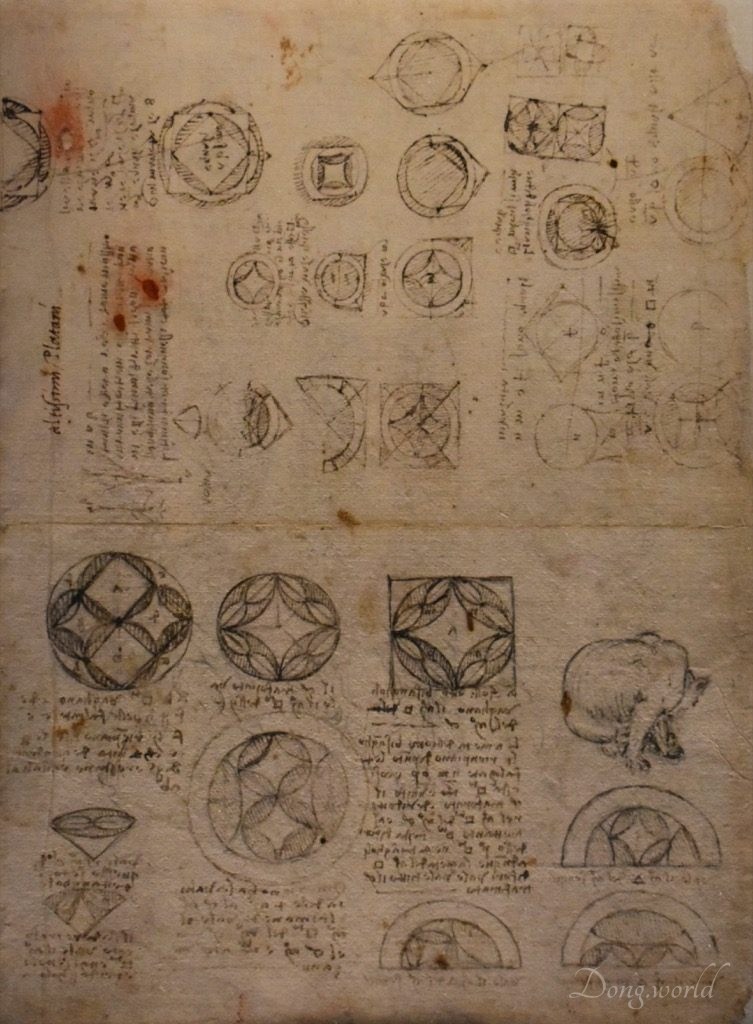

The “Codex Atlanticus” is a twelve-volume, bound set of drawings and writings by Leonardo da Vinci, the largest of such sets. Its name comes from the large paper used to preserve the original da Vinci notebook pages, which was used for atlases. As I learnt from the info board on site, in the late 16th century, the sculptor Pompeo Leoni, son of Leone Leoni, by dismembering some of Leonardo’s notebooks, gathered more than 1,700 drawings and writings by the master in one big volume consisting of 402 pages. In 1637, Pompeo Leoni’s collection, together with 11 other manuscripts by Leonardo, was donated to the library, and the 12 volumes became today’s “Codex Atlanticus”. The codices have been preserved here ever since expect for the Napoleonic period when they were taken to Paris.

Currently, the Codex comprises 1,119 pages, covering Leonardo’s thoughts for a period of more than 40 years, from 1478 to 1519. With approximately 2,000 drawings and notes, it covers a great variety of subjects including engineering, hydraulics, mathematics, optics, anatomy, architecture, geometry, astronomy, botany, flight, weaponry, musical instruments and so on. The 20 folios exhibited here mainly deal with technical, military and architectural themes but they also contain many sketches of human figures and animals, an interest that the master had developed since his apprenticeship at Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop. Now, I’ll introduce to you one by one the 20 folios based on the order they are presented in the library and point out some interesting or curious assumptions about them. I hope they will assist you gain a deeper understanding of Leonardo’s genius and influence.

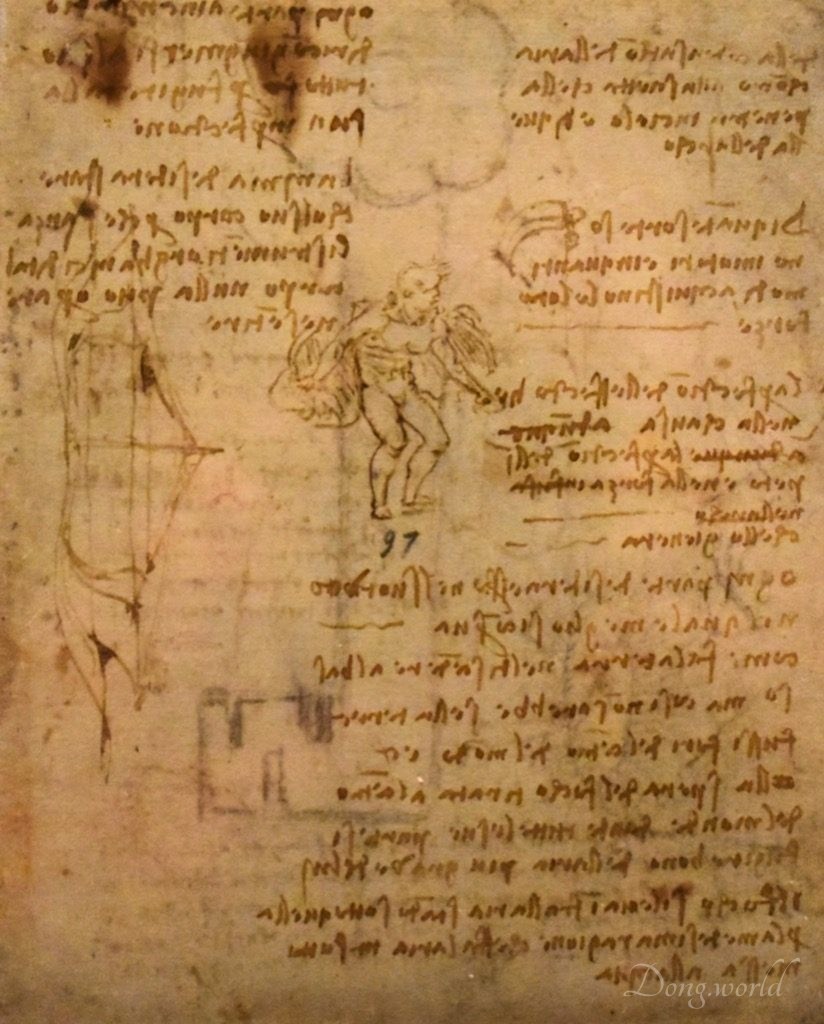

f. 166 r

This page dates to Leonardo’s first stay in Milan and the notes on it deal with natural elements. In the middle, we see a winged-man, who is probably related to the study of flight (on the verso of the sheet), a theme that Leonardo was committed to at that time.

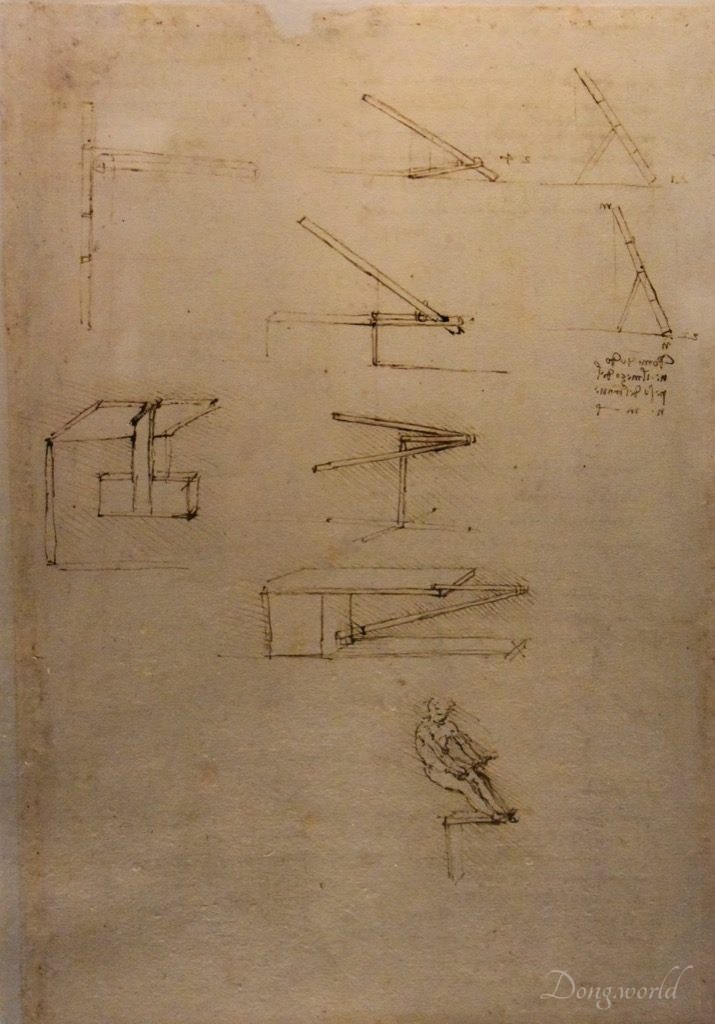

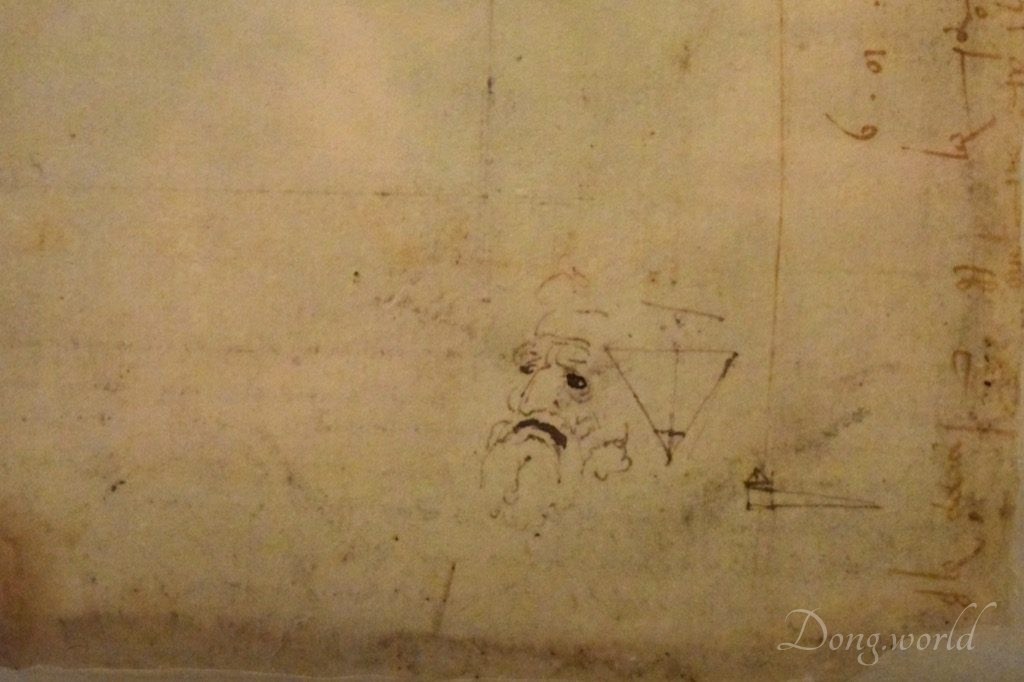

f. 724 r

On this page, we see that Leonard was studying how to keep a protruding flat surface balanced while placing weight on it. At the bottom right corner, we see the demonstration of the mechanism by a small sketched figure, who grabs the handlebar while leaning behind, moving his gravity center backwards. Such human figures often appear in Leonardo’s technical drawings to better explain the machines’ operation. If you take a close look at the figure, you will notice the hatching (in fine art and technical drawing, the shading of an area with closely drawn parallel lines), which both highlights the figure and his back-ward movement.

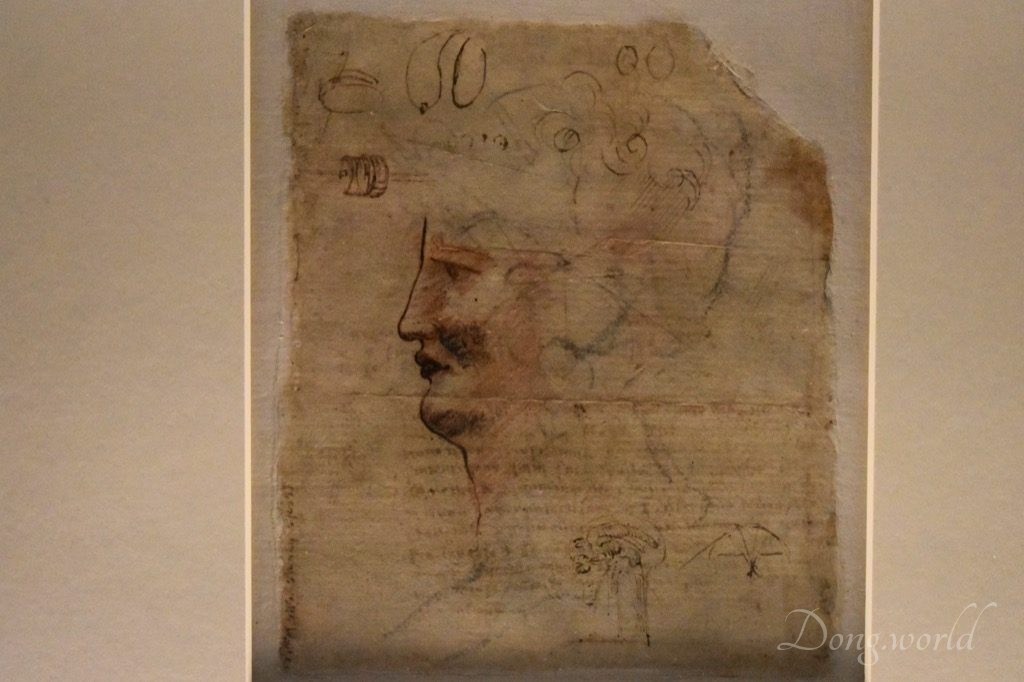

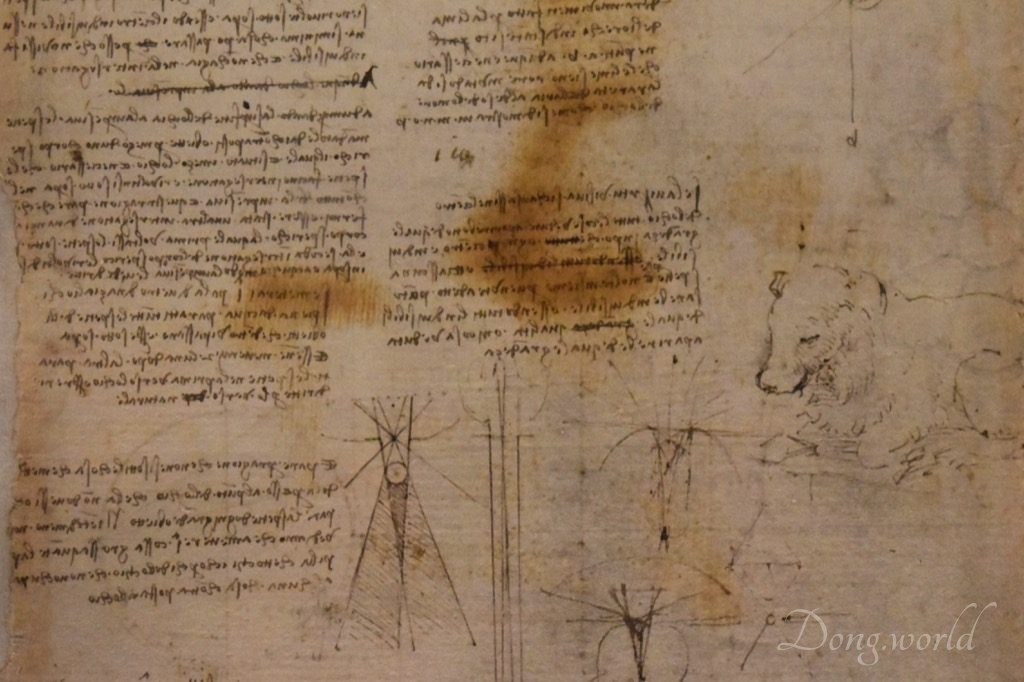

f. 716 v:

This notebook page comes from the registers of the Milan Cathedral, which can be proven by the accounting records on the margins and the date. On the right bottom corner, we see a small drawing of an old man’s face shown in three-quarter view, which is characteristic in all of Leonardo’s portrait paintings. He is depicted with a tragic expression and an arched mouth, features reminiscent of those of Greek theatrical masks.

f. 58 br:

This drawing by one of Leonardo’s pupils probably depicts the so-called Monster of Ravenna, a fictional late Renaissance monstrous birth who appeared in early 1512 near the city of Ravenna. Its left foot was an eagle’s claw and it was said to have a horn on the head, bat wings instead of arms, a female breast on the right and male on the left, both female and male sex organs and an eye on the right knee. These grotesque features were symbolically interpreted by opponents of both the Catholic Church and the Protestant Reformation, but as I learnt from Wikipedia, at that time, it was more commonly held that the “monster” was a sign of the outcome of the Battle of Ravenna. This drawing, together with the one in case No. 4 (which is not shown in this post), testifies to the spread of interest in physiognomy and grotesque in Leonardo da Vinci’s workshop.

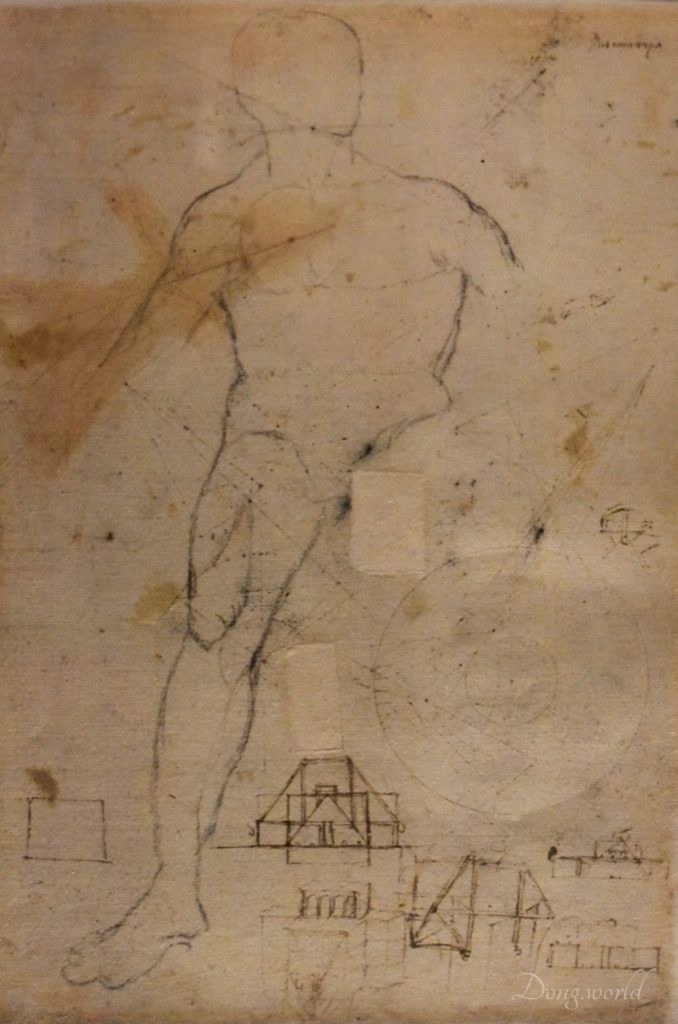

f. 575 r:

On the left of the page we see a big figure but barely outlined, which is probably a copy of an ancient statue by Leonardo. It’s also possible that it is a practice by one of Leonardo’s pupils, who reused the paper where the master had previously planned some architectural designs. In the middle, we see two lacunas, which, as I learnt from the info board on site, were made by Pompeo Leoni, who cut the sketches of a standing figure and a small profile. They now belong to the Windsor Collection.

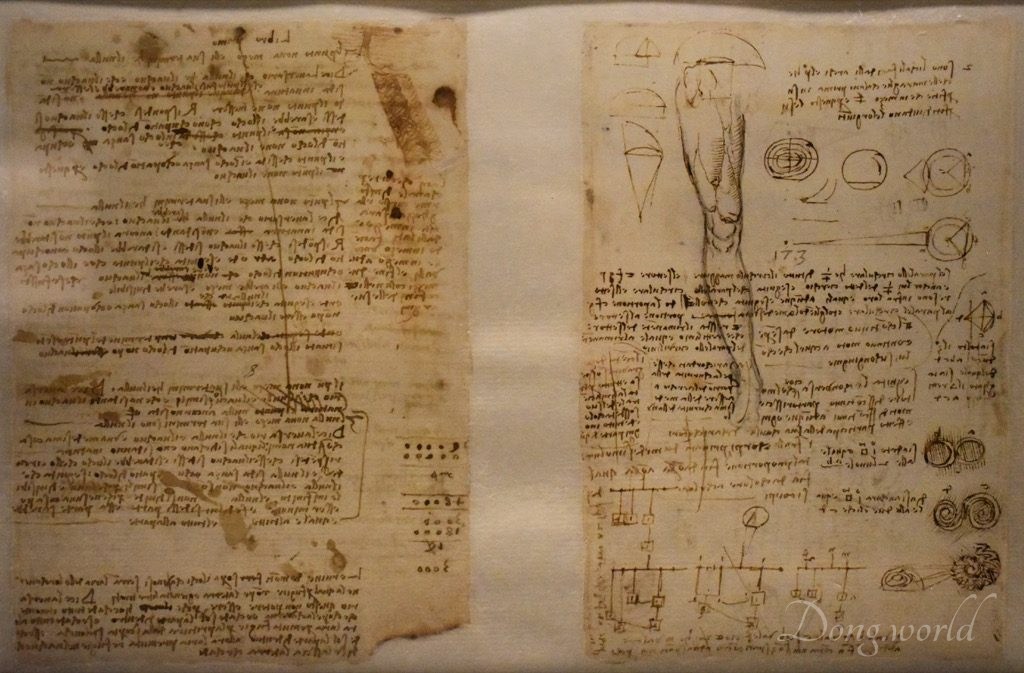

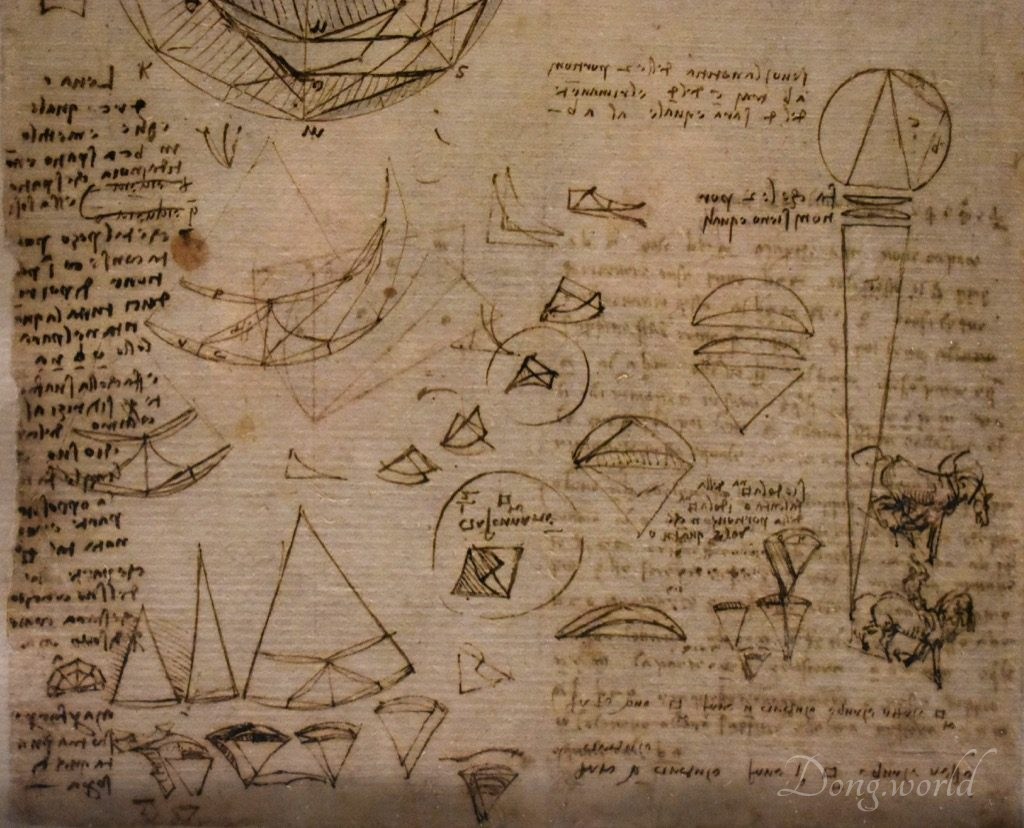

f. 784 v:

The notes on these two pages deal with various themes such as geometry, theories on painting and most importantly, statics. The anatomical drawing of a male leg on the right is probably related to this subject, a demonstration of a balanced system of weight, counterweight and junction.

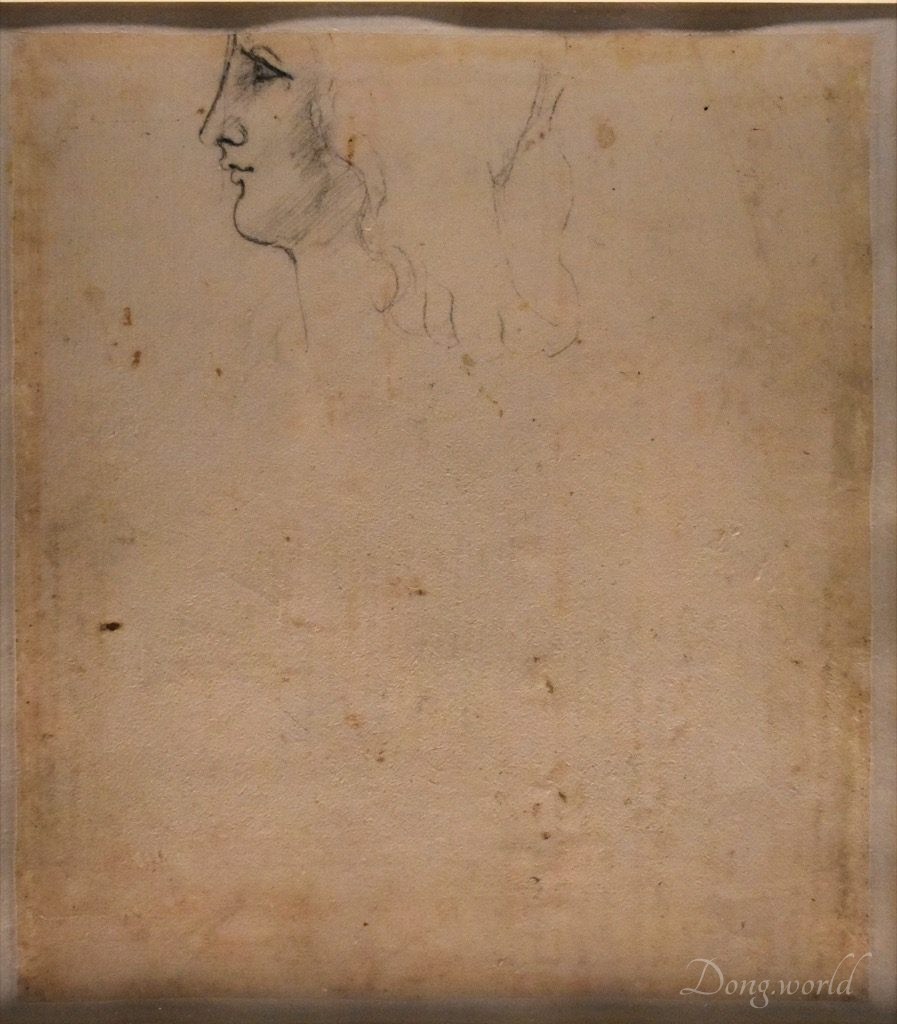

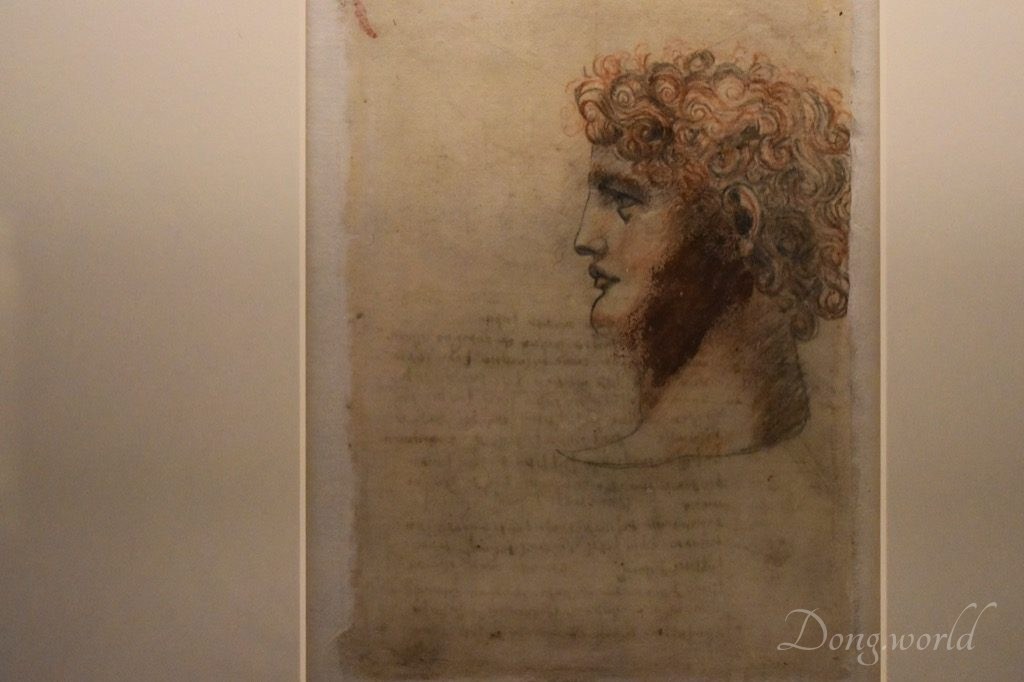

f. 918 v:

The bust of a young man in profile was drawn by a pupil of Leonardo and his upper part is outlined in detail in black pencil while his eye and lower part are barely sketched. More importantly, on the recto of the folio (which is sadly not exhibited), Leonardo drew a famous geographical map of the Chiana Valley in Tuscany, with the villages of Montecchio and Castiglione Aretino (nowadays Castiglion Fiorentino).

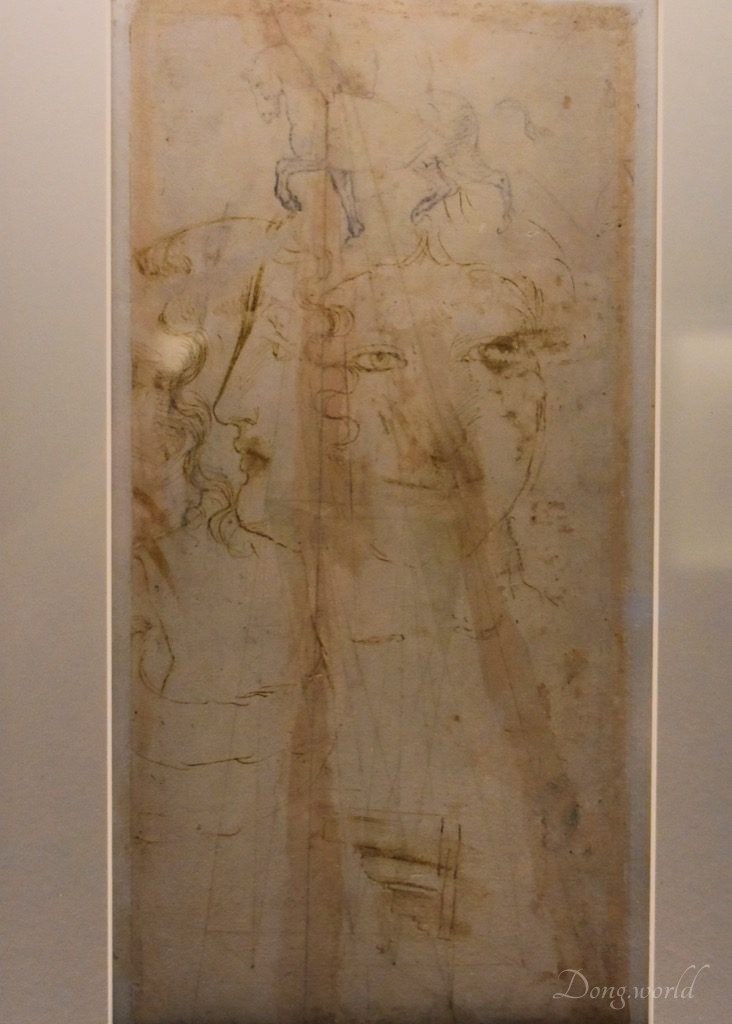

f. 355 v & f. 118 va-b:

The three portraits above were all done by Leonardo’s pupils and are dedicated to the theme of profile. It is clear that all of them are merely didactic exercises and share certain features of a common model, that is to say, the so-called “Salaì” type, named by scholars after the student and servant of Leonardo. Originally called Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, he is better known as Salaì and is thought by some to be the model for the master’s “St. John the Baptist”, “Bacchus” and even “Mona Lisa”. Salaì’s life story and connection to the master are rather curious and mysterious and if you are interested, you can take a look at my previous post, in which I talked about them when I was introducing his version of “St. John the Baptist”. In the Windsor Collection, there are two drawings of a young man which are traditionally considered to be the portraits of Salaì by Leonardo. The middle profile we see above is actually highly reminiscent of those two. Anyway, all the three portraits show reference to ancient numismatics and statuary.

f. 786 vb:

The three female faces between a horse on top and an architectural element at the bottom were drawn by one of Leonardo’s pupils and the particular effect of the representation is achieved by the geometric drawing of a pyramid. Can you recognize the three faces on the page?

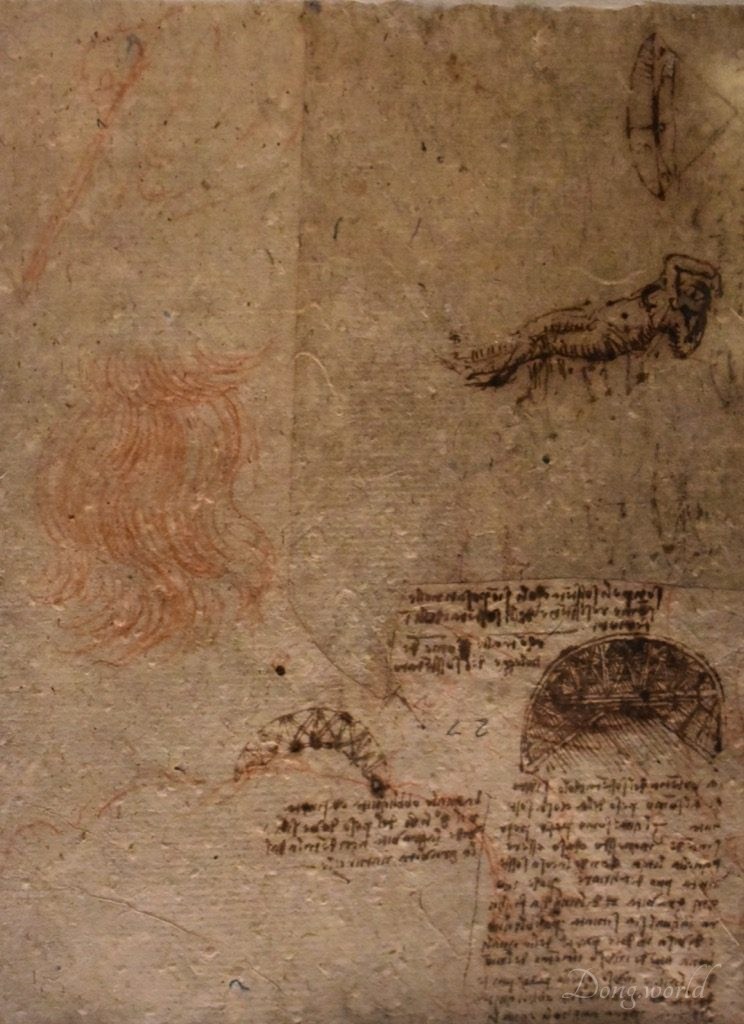

f. 770 v:

On the left of the page we see a hand holding a pen and a lock of hair or beard in red pencil and they are by the hand of a pupil of Leonardo. To be honest, I don’t know how scholars decide which drawings are by the master himself and which drawings are by his pupils because to me, the lock of hair or beard is very similar to that in the assumed self-portrait by Leonardo, now preserved in the Royal Library in Turin. On the right, we see a female figure, and she is said to be a quick sketch by Leonardo, representing the ancient statue of the “Sleeping Ariadne“, now housed in the Vatican Museums in Vatican City. It was bought by Pope Julius II in 1512 and is one of the most renowned sculptures of antiquity. The small and simple drawing plays an important role in attesting to the master’s interest in ancient sculpture.

f. 559 r:

Besides drawings and notes on optics, we see a crouching dog on the right of the folio. This animal was sketched by Leonardo in several different occasions and here, it was probably drawn when the master was taking a break from his study.

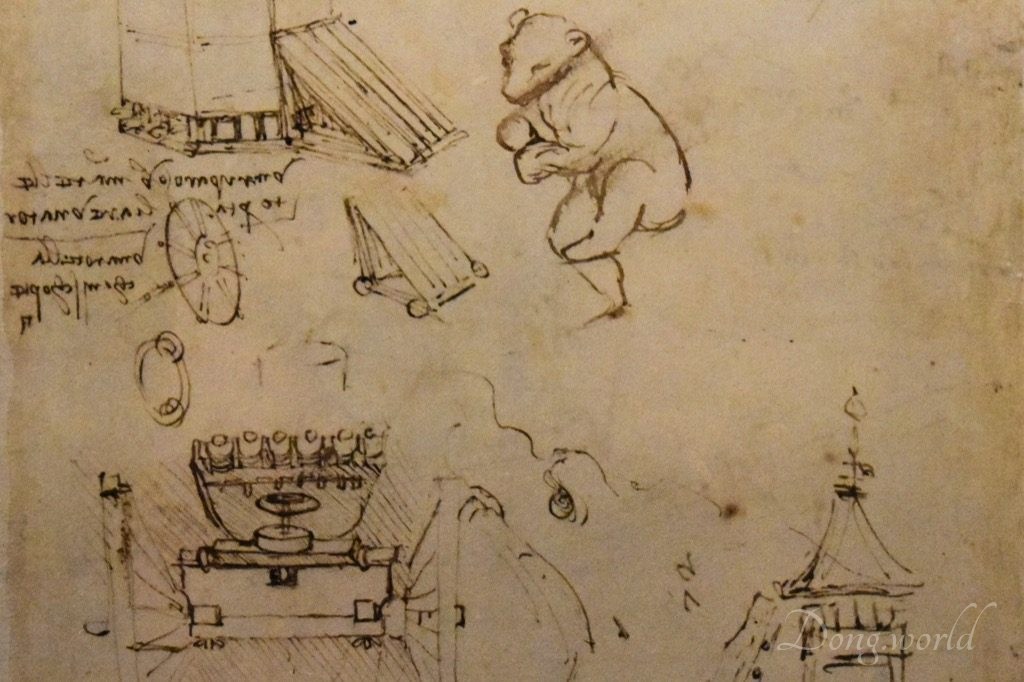

f. 977 v:

Most of the page is dedicated to the design of war machines but on top, we see a sketch of a bear cub, an animal that Leonardo drew and described in various occasions. For example, on f. 520 r, the master describes the techniques used by the hunters of Valchiavenna to capture these wild animals.

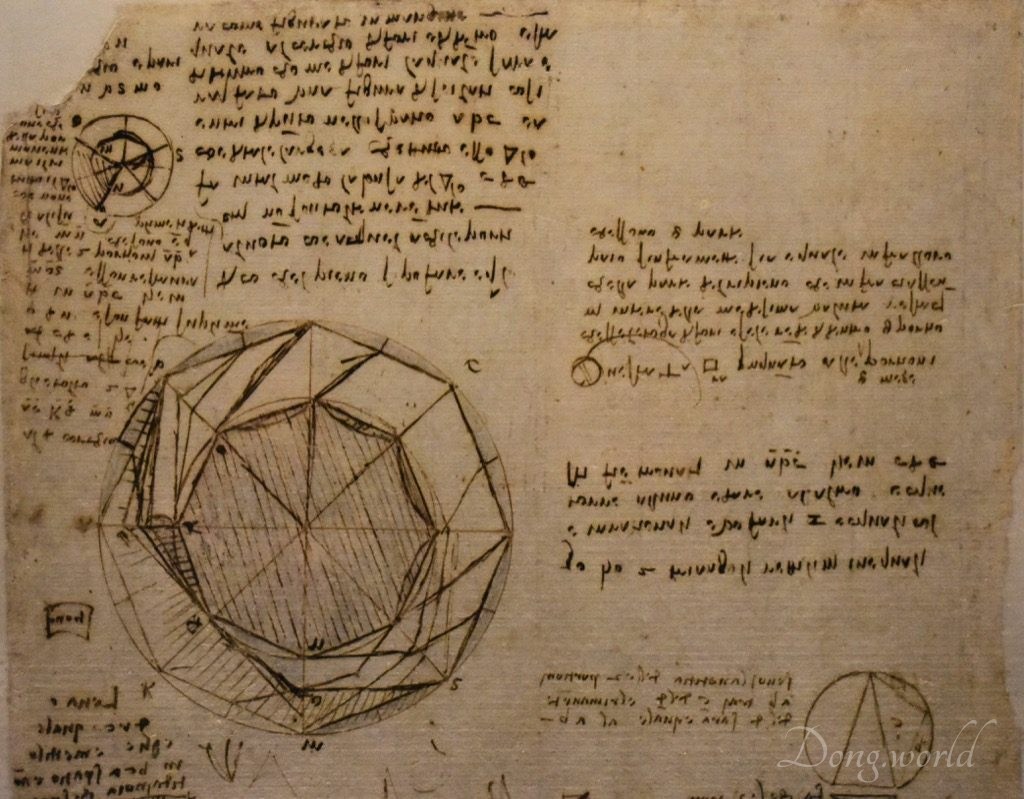

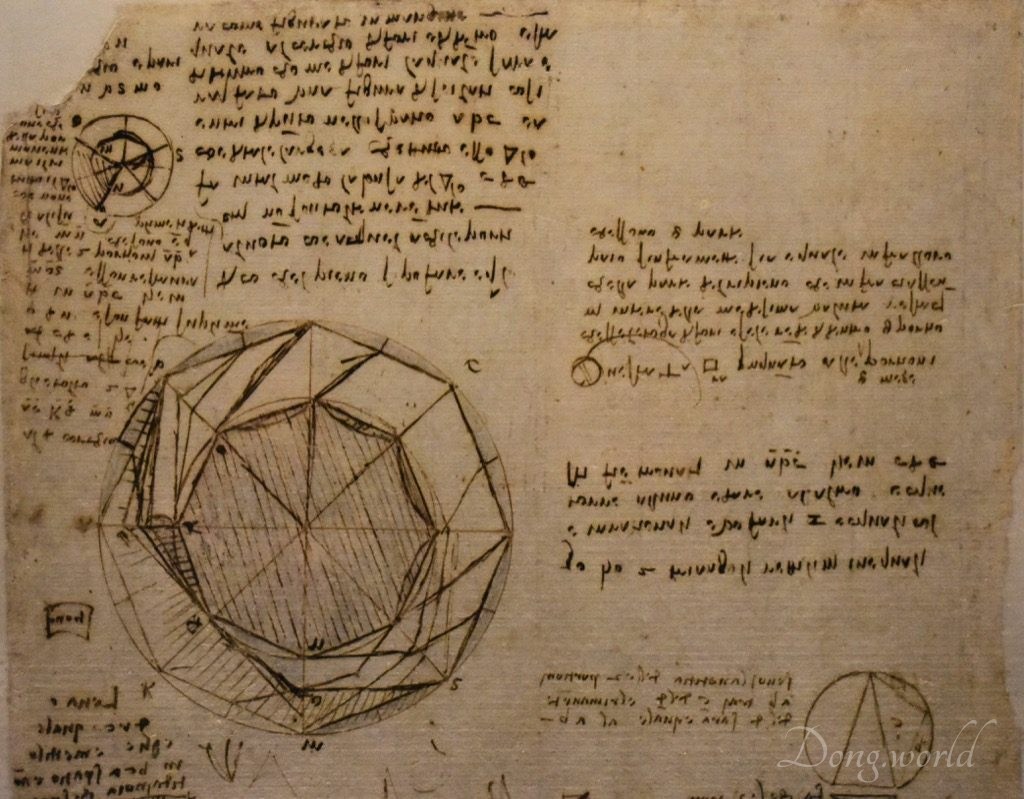

f. 354 r:

This folio is probably my favorite among all the 20 folios exhibited in the library. Most of it is occupied by drawings and notes on geometry, in particular, the classical problem of “squaring the circle” proposed by ancient geometers. It is the challenge of constructing a square with the same area as a given circle by using only a finite number of steps with compass and straightedge. In 1882, the task was proven to be impossible. From this page, we see that Leonardo was also trying to solve the unsolvable problem. On the right bottom corner, two horses seem to be going down a very steep slope, which are the results and evidence of Leonardo’s detailed study of the movements of the animal.

f. 268 r:

Besides various geometrical diagrams, there is a drawing of a cat licking its rear paw. As I said above, Leonardo’s interest in animals already developed when he was working in Verrocchio’s workshop and later in his life, he’s been studying them a lot. The car, together with the dog and bear cub I mentioned above might have been copied live by the master, probably when he was taking a break from his studies. This assumption can be testified by the appearance of small sketches of the animals among the complicated designs, diagrams and notes of various subjects such as optics, machinery and geometry. The cat is a popular subject among Leonardo’s studies which appeared from his early “Study of the Madonna and Child with a Cat” to his late drawings now in the Windsor Collection.

Only from the 20 pages we already see Leonardo’s wide interest in nature, aeronautics, physics, machinery, engineering, physiognomy, grotesque, ancient statue, architecture, geometry, (portrait) painting, statics, anatomy, topography, animal (movements), optics and so on. Can you imagine how many topics are covered in the 1119 pages of his “Codex Atlanticus”? What’s more, though this is the largest of such sets, there are still “Codex Arundel” and “Codex Leicester”, in which we can look into much more of Leonardo’s research. What a polymath! Now I finally understand why he is called a “Universal Genius” of “unquenchable curiosity” and “feverishly inventive imagination”. All in all, I strongly recommend you visiting the Ambrosian Library and allow yourself to be overwhelmed by the power of knowledge and wisdom of human beings.

Now, before returning to the room (Room 8) where we stopped in the previous post, I’ll introduce to you Room 19 first, which exhibits many outstanding portraits by Francesco Hayez and a particularly emotional painting by Emilio Longoni.

“Portrait of Giuseppina Negroni Prati Morosini” by Francesco Hayez

Francesco Hayez was an Italian painter and the leading artist of Romanticism in mid-19th-century Milan. Renowned for his grand historical paintings and political allegories, he also created exceptionally fine portraits.

Commissioned by her husband, Count Alessandro Negroni Prati, this painting portrays Giuseppina Negroni Prati Morosini and was exhibited at the annual exhibition of the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in 1853. Despite of the superb quality, which can be noticed in the luminous rendering of the face, detailed representation of the lace sleeves and collar and convincing depiction of the elegant gesture (a ringed hand holding a book which is slightly open), the portrait didn’t receive much appreciation by art critics at that time.

The “Portrait of Giuseppina Negroni Prati Morosini” is actually one of the four portraits executed by Francesco Hayez for the Morosini family between 1852 to 1854, a noble Venetian family that gave many doges, statesmen, generals and admirals to the Venetian Republic, and cardinals to the Church. In the 17th century, the family moved to Como and later to Lugano. The four paintings are portraits of Giuseppina Negroni Prati Morosini, her husband Alessandro Negroni Prati Morosini, and her parents Emilia Maria Magdalena Taddhea Zeltner and Giovan Battista Morosini and are donated to the Ambrosian Art gallery in 1962 by Vincenzo Negroni Prati Morosini. From them, we can see a common feature of Hayez’s portraits, that is to say, the austere, often black and white, clothing of the sitters.

“Mary Magdalene” by Francesco Hayez

This is another work by Hayez in this room and it attracted my attention when I was passing by. If you didn’t read the title would you think this is a painting of a biblical figure? The gradual shading of the eyes and mouth is to some extent similar to that in Leonardo da Vinci’s works, which almost gives the facial features a 3-D effect. With one hand holding her heard while looking up, what is she thinking about? Telling from the tightened eyebrows, she seems anxious and concerned, but telling from her big eyes, in which tears seem to be welling up, we see melancholy and sorrow. Isn’t it the best kind of painting which could not only convey the psychology of the characters but also evoke the inner feelings of the observer, thus creating an emotional communication between the two different worlds of the painter and of the viewer?

“Locked out of School” by Emilio Longoni

This painting is one pf the most outstanding of Longoni’s early works and it was also the first time that the artist tried his hand on a canvas of such size. In it, two girls are locked out of school and standing next to each other hand in hand. The older girl is leaning again the wall and looking sad but the younger one carrying a basket looks quite joyful. The direct and strong expression of the two girls’ emotions won this work immediate admiration from both the society and art critics and after I looked at the younger girl for some time, I even felt that the smile was so bright and shiny that it brought out the happiness and high spirits of myself.

Now, let’s go back to the room (Room 8) where we stopped in the previous post.

Room 8 & 9

Room 8 is also called the “Hall of the Medusa” because of the fountain carved by Giannino Castiglioni, and together with Room 9 (Hall of the Columns), it was acquired by the Art Gallery in 1928. Their particular decorative atmosphere dates back to the Perfect Giovanni Galbiati, who between 1929 and 1931, appointed the commission to the architect Alessandro Minali. The rooms, which were closed after the Second World War, have been recovered and have kept as much of their original taste as possible. In the display cases between the two rooms, the most important collections of objects in the Ambrosiana are kept. For example, we can see the armillary spheres from the Settala Collection and a case that keeps a lock of Lucrezia Borgia’s hair, which is described by Lord Byron as “the prettiest and fairest imaginable.” Lucrezia Borgia was an Italian noblewoman of the House of Borgia and the daughter of Pope Alexander VI and Vannozza dei Cattanei. She reigned as the Governor of Spoleto, a position usually held by cardinals, in her own right. I read from leonardo-ambrosiana.it that the gloves Napoleon wore at Waterloo are also conserved and can be seen in the Gallery, but unfortunately I didn’t find them.

“The Annunciation” by Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli

This painting had been originally attributed to Parmigianino, but later, by analogy with some of Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli’s works such as “Marriage of St. Catherine”, it was re-attributed to Bedoli, Parmigianino’s pupil and collaborator. He was an Italian painter active in the Mannerist style, which is visible in this painting. “The Annunciation” is full of symbolic and classical elements such as the classical temple at the background, symbolizing Mary as the temple of Christ, the clothing of Archangel Gabriel (reminiscent of that of Hermes) and the solid column behind him, symbolizing the force of the proclamation, the lilies that the Archangel is holding, symbolizing purity and the luminous dove, symbolizing the Holy Spirit.

Room 12 & 13

Room 12 (Esedra Room) was renovated between 1930 and 1931 on the occasion of the two-thousandth anniversary of birth of Virgil, an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period who wrote three of the most famous poems in Latin literature, that is to say, the “Eclogues“, the “Georgics“, and the epic “Aeneid“. Same to Rooms 8 and 9, Room 12, Room 13 as well as the staircase connecting them were commissioned by the Prefect Giovanni Galbiati and designed by Alessandro Minali. The large mosaic (as you can see in the 1st picture above) reproduces the famous miniature by Simone Martini on the title page of the “Ambrosian Virgil“, which was illuminated by Simone Martini, Giuseppe Flavio on papyrus and is with notes on the margins by Francesco Petrarca. The marble statues inside the niches of the hemicycle above the staircase are works of the early 19th century.

After climbing the stairs, we will come to Room 13, which is also called the Nicolò da Bologna Room, named after one of the most important and prolific manuscript illuminators in 14th-century Bologna. In this room, I’d like to introduce to you a painting called “Winter Landscape with Skaters” by Hendrick or Barent Averkamp.

“Winter Landscape with Skaters” by Hendrick or Barent Averkamp

Born in Amsterdam, Hendrick Avercamp was a Dutch painter. In 1608 he moved from Amsterdam to Kampen in the province of Overijssel and because he was deaf and mute, he was also called “de Stomme van Kampen” (the mute of Kampen). When he was born (the last quarter of the 16th century), it was one of the coldest periods of the Little Ice Age and that’s probably one of the reasons why he specialized in painting the Netherlands in winter. As one of the first landscape painters of the 17th-century Dutch school, he not only created quiet landscape but also added carefully crafted figures to it, which made the scene more colorful and lively. In fact, many of his works are featured with people ice skating on frozen lakes, an activity he probably practiced frequently with his parents during his childhood.

As you can see from the picture above, the subject of this painting is in accordance with Avercamp’s favorite, that is to say, the combination of landscape and genre painting. A technique called “aerial perspective” is applied here, which can be seen in the change of color in the distance, indicating depth. This technique was already used in paintings from the Netherlands in the 15th century and is said to have been invented either by Giorgione or the Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci. The landscape, featuring a high horizon, shows a winter day probably right after a snow. We can see houses, a bridge and most importantly a frozen lake on which people are skating. It is these people, who are of different professions and social status, that add narrative power to the painting. Some peasants and artisans are working, some people with bourgeois clothes are entertaining themselves, some couples are having a walk and some young people are skating and having fun with the snow. It seems Avercamp captured a moment of an ordinary winter day of the village and immortalized it.

As you can see from the title of the section, this painting was either executed by Hendrick or Barent Averkamp, who was the nephew and student of Hendrick and issued to have further developed the genre of painting. Does their story remind you of the one between Canaletto and his nephew Bernardo Bellotto?

“The Presentation of Christ in the Temple” by Giandemenico Tiepolo

Giandomenico Tiepolo was an Italian painter and son of the traditional Old Master Giambattista Tiepolo, who has been described by Michael Levey as “the greatest decorative painter of eighteenth-century Europe, as well as its most able craftsman.” Giandomenico was born in Venice, studied under his father, and already became the chief assistant to him at the age of 13. By the age of 20, he was producing his own work for commissioners. I first heard his name when I was visiting the Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza, which was frescoed by the father-son team. Later in Venice, I saw many other works by the artist, including the ones designed for and later detached from his own house. If you are interested, please read the relevant posts about the two cities respectively.

The Presentation of Christ in the Temple is an early episode in the life of Jesus, describing his presentation at the Temple in Jerusalem in order to officially induct him into Judaism. In this painting, we see that the Presentation is happening under an arch, with the Virgin Mary and St. Joseph kneeling in front of the priest and handing Baby Jesus over to him. The soft color and gentle brushes wrap the figures with bright pink light, which make them stand out in the archway.

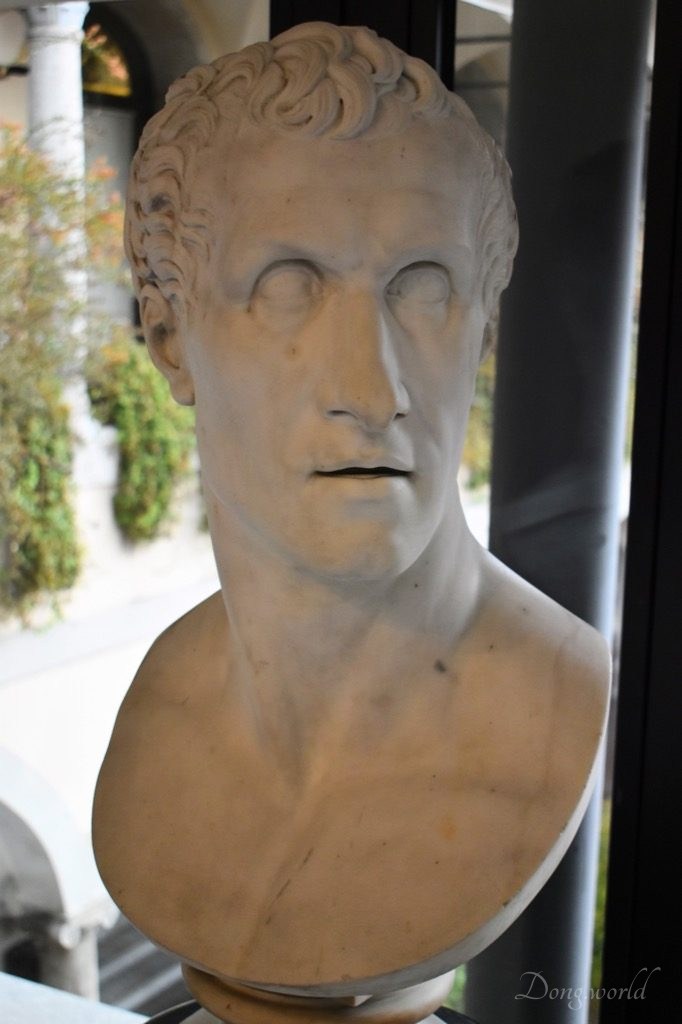

Self-portrait in marble by Antonio Canova

In Room 18, this bust was considered to be a self-portrait in marble by Antonio Canova but recently, as I learnt from lombardiabeniculturali.it, it is re-attributed to Giovanni Battista Monti. In either case, the inspiration came from the idealized models of classical antiquity.

“Courtyard of the Great Spirits”

Either from the loggia of the Art Gallery (on the 2nd or 3rd floor) or from the big glass windows of Room 18, you can look down on the courtyard called the “Courtyard of the Great Spirits” (Cortile degli Spiriti Magni) with a precious archeological collection. During both of my visits, the courtyard was always a place of peace and tranquility. First of all, there were never many people and secondly, though the Gallery and Library were located in the center of Milan, the yard seemed isolated from the outside world and was absolutely quiet. If you are getting tired looking at the masterpieces, why not standing here for a few minutes, taking a deep breath of some fresh air and taking a look at the green plants and let your eyes rest? Or, maybe as the name of the courtyard suggests, give yourself some time to think about what the great spirits are.

By now, in three posts, I have finished giving you a rather detailed introduction to the Ambrosian Library and Art Gallery. There were surprises and regrets during my visits but the general experience was amazing. Raphael’s “Preparatory Cartoon of the School of Athens“, Federico Barocci‘s “The Nativity”, Jan Brueghel the Elder‘s “Vase of Flowers with Jewelry, Coins and Shells”, Hendrick or Barent Averkamp’s “Winter Landscape with Skaters“, Francesco Hayez‘s portraits, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Portrait of a Musician” and Caravaggio‘s “Basket of Fruit” are absolutely unmissable not only because they were created by the “big names” in history but also because they made great contributions to the further and continuous development of western art. As I mentioned above, it is here in the Ambrosian Library that you will have the rare opportunity to see da Vinci’s original notes and drawings from his notebooks, which are not exhibited to the public permanently anywhere else in the world for conservation purposes. From these folios, we can see what he was interested in, thinking about and doing at different periods of his life. Aren’t the codices like the master’s diaries, which record Leonardo’s life and help us look into his superhuman mind? I do hope that some other pages from the “Codex Atlanticus” will be exhibited in the future and the restoration of Raphael’s Preparatory Cartoon will be finished soon and by then, I will surely pay a third or even fourth visit to the Ambrosian Library and Art Gallery.