In my previous post about Modena Cathedral Complex, I focused on the cathedral itself including its history and decorations both outside and inside. Besides, I mentioned some of the most precious items among the Cathedral Museums‘ collections. For example, the eight metopes, which were originally located on the buttresses of the cathedral’s roof depicting fantastic creatures, the portable altar used by St. Geminianus, the famous “Relatio” documenting the construction process of the cathedral, and the Byzantine cross which came from Constantinople during the Crusades. In this post, we will climb the bell tower (Torre Civica) and visit the historic rooms of Palazzo Comunale. If you have read the previous post, please click here to jump directly to the main content of this one. If not, the following chapters will be about the outstanding universal values of the complex, a brief introduction to the city of Modena, and the all-inclusive ticket which is the best choice for the people who are interested in the city’s historical and cultural heritage.

1. Outstanding universal value

As the UNESCO comments:

The magnificent 12th-century cathedral at Modena, the work of two great artists (Lanfranco and Wiligelmus), is a supreme example of early Romanesque art. With its piazza and soaring tower, it testifies to the faith of its builders and the power of the Canossa dynasty who commissioned it.

摩德纳的大教堂、市民塔和大广场: 位于摩德纳的宏伟的12世纪大教堂,是兰弗兰科(Lanfranco)和威利盖尔茨(Wiligelmus)这两位伟大艺术家的杰作,是早期罗马风格艺术的最杰出典范。这所大教堂和与之相配套的宏大广场以及耸入云霄的高塔一起,不但证实了建造者们对皇室的无限忠诚,而且还体现了命令建造这些建筑的卡诺萨王朝的非凡国力。

In order to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list, sites must be of outstanding universal value and meet at least one of the ten Criteria for Selection. Modena Cathedral Complex (including Cathedral, Torre Civica and Piazza Grande) meets

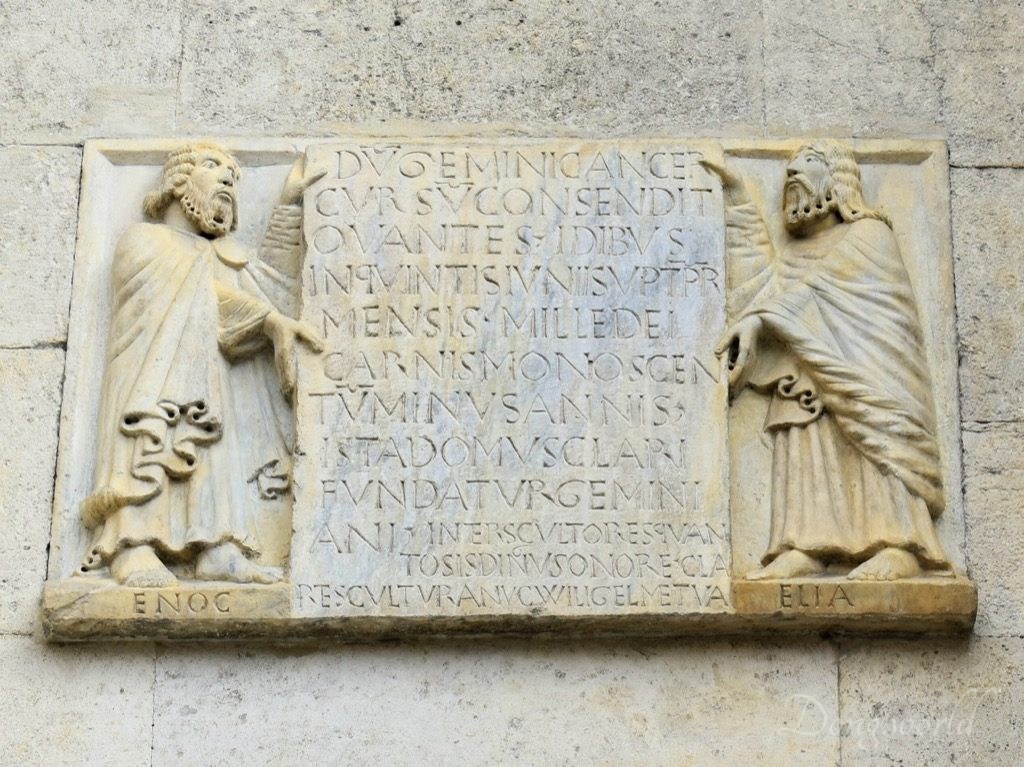

Criterion (i) to represent a masterpiece of human creative genius, because the cooperation between Lanfranco (the architect) and Wiligelmo (the sculptor) demonstrated a new dialogue between architecture and sculpture in Romanesque art;

Criterion (ii) to exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design, because the complex influenced greatly the development of Romanesque art in the Po Valley and Wiligelmo’s innovations had profound influence on Italian medieval sculpture. As commented on the World Heritage website, “At the European level, the sculpture of the Cathedral of Modena represents a privileged observatory for the understanding of the cultural context accompanying the revival of monumental stone sculpture. Only very few other monumental complexes, such as Toulouse and Moissac, can claim to be so important in this respect”;

Criterion (iii) to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared, because the busy urban life reflecting the beliefs and values of the citizens in Northern Italy in the 12th and 13th centuries is reflected on the history of the complex including its square and surrounding buildings;

and Criterion (iv) to be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history, because the cathedral, tower and square constitute one of the best examples of an ensemble in a medieval Christian town where civic (economic, political and social) and religious values were combined and both activities (most of the time) were carried out harmoniously.

Attributed to the architect Lanfranco and sculptor Wiligelmo, the magnificent cathedral and its bell tower (Torre Civica), which are consistent in terms of material and structure, are a supreme example of early Romanesque art, renowned for their exceptional architectural and sculptural quality. The foundation stone of the cathedral, home to the mortal remains of St. Geminianus (4th century), patron saint of Modena, was laid on 9th June 1099, replacing an early Christian basilica. The bell tower, whose construction began either together with the cathedral or at the beginning of the 12th century, was originally a five-storey building and was completed in 1319 with an octagonal section and additional decoration. In addition, the property includes the Piazza Grande, which is surrounded by the City Hall, archbishopric, and some other buildings.

Though the exterior of the cathedral and tower appears in general white and a bit yellow during sunset, if you take a close look, you will notice that it’s made of stones of different types and colors. In fact, these areancient Roman stones recycled from Mutina, the Roman Modena. Besides the outstanding values I mentioned above of the complex, there are two other aspects which shouldn’t be neglected. First, these two buildings are a documented example of the reuse of ancient remains, which was common practice in the Middle Ages before quarries were reopened in the 12th and 13th centuries. Secondly, between the 11th and 12th centuries, the cathedral was one of first buildings where collaboration between an architect and a sculptor was recorded by explicit inscription, which can be found on the west façade (as you can see in the 6th picture above). As commented by the UNESCO, “It also marked the shift from a conception of artistic production emphasizing the quality of the buildings as a masterpiece of the munificence of its founder, to a more modern concept in which the role of the creator is recognised.” I still remember when I was watching and reading about the west façade, a local grandma passed by and talked to me in Italian. Sadly I didn’t understand her at all because I don’t speak Italian but I saw she was pointing at the stone plaque and I realized it must be of particular importance. Later I found out why she was so excited about it. That was the first time I experienced the enthusiasm of the Modenese and I’m really glad that the locals are aware and proud of the treasure that they have.

Between the end of the 12th and beginning of the 14th centuries, the cathedral’s and tower’s decorations developed greatly under the influence of the Campionesi masters, who always took into consideration the principles of the post-Wiligelmo Emilian Romanesque School and the innovations of Benedetto Antelami. What’s more, the documented presence of them provides a significant amount of information about how the works were managed on a well-organized medieval construction site.

2. The city of Modena

First, what do you know about this ancient city? For me, besides the cathedral complex, which meets four out of the ten Criteria for Selection although only one is needed to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list, as a food lover, I knew it was famous for its production of balsamic vinegar, and as an opera lover, I knew it was the hometown of Luciano Pavarotti, who was born and died here. If you love cars, in particular sports cars, you probably know already that Modena is also known for its automotive industry since the factories of the famous Italian sports cars such as Ferrari, Lamborghini, and Maserati are, or were, located here, and both Ferrari and Maserati have their headquarters in the city or nearby. However, do you know that Enzo Ferrari, founder of Ferrari, was actually born in Modena and one of Ferrari’s cars, the 360 Modena, was named after the city itself?

Modena is, in my opinion, so Italian because of its “broken” buildings, “dirty” façades and “messy” streets. Please don’t think negatively of those words because without them, Italy wouldn’t be Italy. The city itself isn’t as clean as Zurich or as developed as New York but that’s why it’s lovely and special. It presents traces of history which are reflected on architecture, artworks and public spaces, and allows the curious and respectful minds to have a conversation with it.

3. Visit to the World Heritage site

Inscribed in 1997, this site has been managed and protected properly for more than 2o years. Therefore, its tourism has developed and matured and the visits are very well-organized nowadays. Why do I say so? In fact, this is one of the few cities I’ve been to in Europe where an all-inclusive ticket,which is entirely dedicated to the attractions related to their World Heritage, is available. In Modena, the ticket gives you access to the Ghirlandina Bell Tower (Torre Civica), Cathedral Museums, the historic rooms in Palazzo Comunale and the Municipal Balsamic Vinegar Factory and it only costs 6 euros per person. On the ticket, you can see the opening hours of the attractions. Please note, if you are visiting Modena on some bank holiday in Italy, I recommend you checking the news and events on the official website because adjusted opening hours may apply. The cathedral is not listed on the ticket because it can be visited free of charge. It’s open every day from 7:00 to 12:30 and from 15:30 to 19:00, but visits are not allowed during religious services or on Sunday mornings.

Unfortunately, during my visit, the interior of the cathedral was under restoration, but I visited the crypt and saw most of the artworks in the nave and aisles. In three posts, I’ll give you a detailed introduction to the property as well as some buildings in the buffer zone. The first post will be about the cathedral and Cathedral Museums, the second will be about the bell tower and the historic rooms in Palazzo Comunale, and the third will be about Piazza Grande and the Municipal Balsamic Vinegar Factory.

4. Ghirlandina Bell Tower (Torre Civica)

The Ghirlandina Tower (89.32 m high), which from bottom to top is composed of a square base (11 m *11 m* 50 m), an octagonal section, a tented roof, a sphere and a cross, is the symbol of Modena and can be seen from almost everywhere in the city. Its name, Ghirlandina (Little Garland), probably refers to the decorative balustrades, which look like a garland, crowning the spire. Admission is included in the Modena UNESCO Site All-inclusive Ticket and when you are at the ticket office, don’t forget to ask for an info sheet in your preferred language, in which a lot of information is provided about the bell tower, including its construction process, decorative elements and various chambers. My introduction below will also be mostly based on it.

4.1 Construction process

Unlike the construction process of the cathedral, which is well-documented in the “Relatio”, chronology of the bell tower is still much debated, in particular the early period. Common belief holds that the first five floors were built from the Romanesque period till the end of the 12th century, and later the octagonal section (including the tented roof) and additional decoration were added by the Campionesi masters, who finished the edifice in 1319. Throughout the 16th century, restoration was carried out on the octagonal section and in 1588, the spire was raised lightly higher. Later, in 1609, the wooden staircase was built inside the tented roof, at the end of the 19th century, buildings leaning on the tower were demolished and in 1901, the current entrance on via Lanfranco was opened.

As you can see from the pictures above, the cathedral and tower form an organic whole because their construction methods and materials (both inside and outside) are identical, that is to say, both are structured in brick, which can be seen from the inside, and cladded in more than 20 different kinds of stones recycled from the Roman town Mutina (Modena during the Roman era). However, as for the tower, from the belfry upwards, materials were specially purchased for the construction. Do you remember when I introduced to you the outstanding universal values of the complex, I mentioned that it reflected the busy life of the citizens in Northern Italy in the 12th and 13th centuries and is one of the best examples of an ensemble in a medieval Christian town where civic (economic, political and social) and religious values were combined? The belfry played a double role, both religious and civic. The ringing of the bells not only marked the beginning of religious services but also celebrated key events in the city’s history, signaled opening of the city gates and warned the citizens in case of danger. Sadly, the belfry is not accessible to visitors but we can reach one floor lower, which is the “Torresani”, Chamber of the Tower Guards. From this room, there is a great view of the city.

If you take a close look at the tower (by comparing it to the cathedral for example), you will notice that it’s leaning towards south-west, which is due to ground subsidence. Degree of inclination varies at different levels because corrections were made in the wake of subsidence which occurred during the construction process. Above via Lanfranco, you will see two arches connecting the tower and cathedral, which were first added in the 14th century, probably as a means of dealing with the inclination, and renovated at the beginning of the 20th.

4.1 Decorative elements

The tower, both outside and inside, is richly adorned. On the exterior, arches, simple or interwoven, were sculpted under the ledges (stringcourse) of the first five levels and at the corners, we see sculptures depicting imaginary beasts (1st level), natural animals (2nd level) and human figures (3rd level). On the eastern side of the second level, there are three panels of Roman origin featuring plants and animals; on the southern side of the third level, we see the head of Medusa; and on the fourth and fifth levels, the pillars of the lancet windows, either double or triple, are all surmounted by intricate capitals. It is said on the info sheet that the capitals (including the ones inside the Chamber of the Tower Guards) as well as the corner sculptures were created in a similar way and style to the ones decorating Porta Regia (Royal Porta), and therefore, are very likely works of the Campionesi masters. In 2011, traces of red decoration were discovered under the arches along the eastern side of the second level and are also believed to have been left by the masters, providing important insights into medieval monument decoration.

4.2 Chamber of the Stolen Bucket

Now, it’s time to enter the tower and do some climbing. Please note, there is no correspondence between the stringcourses of the exterior and floors of the interior. Between the ground floor and the first stringcourse (outside), the Chamber of the Stolen Bucket can be found. Because of their thick walls, both the chamber and the passageway housed the treasury of the City Council, which contained the city’s archives and many relics and precious objects belonging to the cathedral. The name of the chamber comes from the wooden-iron bucket hanging below its roof, which according to legend was stolen by the Modenese from a public well in via San Felice in the center of Bologna during the Battle of Zappolino, the only battle of the War of the Oaken Bucket. As you can see from the picture above, there’s no bucket at the end of the chain. Was it stolen back by the Bolognese? It was actually on loan to Bologna for an event as an expression of renewed friendship between the two cities, but don’t worry, the real one, for security reasons, is now kept and exhibited in the Palazzo Comunale, which we will visit in the next chapter. If you are interested, when we see the original, I’ll tell you more about the War of the Oaken Bucket between Modena and Bologna. This war trophy soon became treasured as a civic symbol and was made famous by the poem of the same name (1622) by Alessandro Tassoni:

But the bucket was soon to be locked away,

In the tallest tower is remains to this day.

Up on high the trophy hangs bound

By a great chain nailed far off the ground.

The decoration of the room reflects Gothic style, and therefore probably dates back to the 14th century. Frescoed from bottom to top, it features four walls which look like graters and a ceiling, which looks like a starry sky. If you use your imagination, the “grater” motifs seem to have been designed to imitate fine fur, which was once used to decorate mantles of emperors.

4.3 Chamber of Scientific Instruments

From this floor, we have a clear view of the internal structure of the tower. Flights of stairs intersect with four corner columns and sometimes even overlap the big windows. Surprisingly, like the 22 different kinds of stones which were used to clad the exterior, the bricks used for completing the interior were also taken from the ancient buildings of the Roman town, Mutina. In order to calculate preciously the inclination of the tower, in 1898 a number of measurements were carried out by letting down two plumb lines from the spire. The marble dowels which fixed the points of reference can still be seen nowadays. Since 2003, monitoring of the inclination has been entrusted to an automatic control system, part of which is a copper tube (as you can see in the pictures above) that runs through this entire room and contains an electronic pendulum. All the sensors are connected to a computer which records and archives the measurements for interpretation by special technicians. Also on this floor, I saw a time capsule, which contains more than 2000 messages from visitors to the future citizens and was closed on 8th April, 2018. Connecting the Roman, medieval and modern city, it will be reopened in 2099, one thousand years after the groundbreaking of Modena Cathedral.

4.4 Chamber of the Tower Guards

After climbing a bit more than 20 meters, we will arrive at the “Torresani”, Chamber of the Tower Guards, which is located on the fifth level. Compared to the bell towers in Split and Trogir in Croatia, I felt much calmer here because on one side of the staircases were the thick walls of the tower and on the other side were low walls, but still thick, with handrails. If you have acrophobia, just walk along the tower walls so that you won’t see how high you are. Completed by 1184, this room was where the tower guards lived, whose presence is documented from 1306 till the second half of the 19th century. They watched over the city, gave signals for the opening and closing of the city gates and rang the bells to mark the hours and alarm and summon the residents in case of danger. From here, there’s an amazing view over the city of Modena but the glass windows and fencing nets to some extent obstruct it. If you want to take nice photos, I’m afraid you will have to stand on your toes and zoom in the lens until the irony lines are out of the image.

As for the decorations of this room, the fresco featuring the coat of arms of Modena City Council, which is surmounted by the eagle of the d’Este family bearing the ducal crown, was probably executed in the 16th century and repainted at the beginning of the 18th. It is written on the info sheet that the north-west corner pillar houses the spiral staircase leading to the belfry, where eight columns can be found, each topped with a capital. Nevertheless, according to other sources and my own experience, the columns are actually in the Chamber of the Tower Guards, among which the Capital of the Judges, the Capital of David and the Capital of the Lions are the most interesting. The Capital of the Judges (southern lancet) represents good and bad judgements and the inscription tells us that an unfair judge, corrupted by money, is likely to pass a sentence which does not reflect his true belief on the matter. The Capital of David (eastern lancet) features the themes of music and dance and among the scenes, we can spot a bearded man with a crown presumably representing King David, who was commonly regarded as the spiritual father of arts in the Middle Ages. There’s no document confirming that the capitals, probably sculpted by the Campionesi masters, were designed for the tower but their themes, both religious and civil, do mirror the double role of the Ghirlandina Tower.

4.5 Tented roof

The Chamber of the Tower Guards is highest point we can reach as visitors and above are the belfry, octagonal section, and spire. The octagonal section features eight sets of lancet windows, which are visible from the outside, and four of them are bricked up. Together with the spire, it was completed in 1319 under the supervision of Anselmo da Campione, and constitutes a single inner space which is around 30 meters high. These two sections were structured in brick and decorated with stone slabs on the outside, many of which were replaced between 1890 and 1896. Inside, the walls are plastered and during the renovation between 2008 and 2009, part of a fresco was discovered, which dates back to the 14th century. It is assumed that in the past, the entire interior was painted. What’s more, a helical staircase with 119 steps leads to the two outer balconies, which are surrounded by decorative balustrades. As I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, it was probably these balustrades, which look like a garland, that gave the tower its name. The wooden staircase was supported by iron brackets, which showed signs of weakening and was recently combined with 22 new ones.

5. Palazzo Comunale

The elegant arcade of Palazzo Comunale frames the north-east edge of Piazza Grande and is now home to many shops, restaurants as well as the Tourism Office, where you can ask for information and buy the all-inclusive ticket which I mentioned above. Please note:

- on 31st January, Sundays and holidays, the historic rooms of Palazzo Comunale are open from 15:00 to 19:00 and can be visited with a small fee (2 euros if I remember correctly), which is included in the all-inclusive ticket;

- the rooms are closed on Easter Sunday, Christmas Day and 1st January;

- on other days, the rooms are open from 9:00 to 19:00 and the admission is free to the public.

Originally, Palazzo Comunale was composed of a series of buildings constructed during different periods of time and later, they were organized into a single and harmonious complex. Seen from the square, the most eye-catching building is probably the Clock Tower, which gained its current appearance in the 16th century. In 1508, designed by Bartolomeo Bonascia, the octagonal cupola was erected and in 1520, the balustrade crowning the quadrangular block was installed. The sculptures around the clock face (including the frieze above it) were added around the mid-16th century. In 1730, a new clock designed by Ludovico Riva was installed, which was later replaced by one with two faces, designed by Ludovico Gavioli. This is the clock we see nowadays. In 1761, the marble balustrade around the balcony of the Immaculate Conception of Virgin Mary was built and the statue inside was placed there in 1805, replacing another statue of the Virgin with Child and Young St. John made of terra-cotta. Under the balcony, we see a Renaissance stairway, which will lead us to the entrance to the five historic rooms which are open to the public inside the Palazzo Comunale. Sometimes there are guide tours but I guess they are only in Italian (at least according to my experience). Don’t worry. The info boards on site are both in Italian and English so if you are interested, you can learn about the rooms by yourself.

5.1 Chamber of the Confirmed

Upon entering, the room you are in is called “Chamber of the Confirmed”, which is home to the portraits of some illustrious Modenese citizens, executed by Girolamo Vannulli in the second half of the 18th century. They can be seen against a trompe l’oeil scenery, which was created by Antonio Cabonari in 1770. The most important object in the room, as you might have realized, is the wooden-iron bucket in the center, which doesn’t have much material value but is highly symbolic. Stolen by the Modenese soldiers from a well in the center of Bologna, it provoked the Battle of Zappolino, which Modena won. The so-called War of the Bucket was actually an episode in the over-300-year-long struggle between Guelphs and Ghibellines, which were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of central and northern Italy. During the 12th and 13th centuries, rivalry between these two parties formed a particularly important aspect of the internal politics of medieval Italy and the Investiture Controversy, which refers to the conflict between the Church and the State in medieval Europe over the ability to appoint local church officials through investiture, lasted till the 15th century. The war trophy, or in other words, the “Stolen Bucket”, was made famous by the poem of the same name (1622) by Alessandro Tassoni and has always been regarded as a civic treasure. In 2015, during the 45oth anniversary of the poet’s birth, scientific research proved that the bucket was original.

Now, let’s turn right and enter The Fire Room.

5.2 The Fire Room

The name of this room probably came from the large fireplace which was used in the winter time to prepare embers for distribution among the peddlers in the market (so that they could start their own fire), a public service much appreciated by the Modenense. On the walls, the Siege of Modena (43 – 42 B.C.) and the Path to Power of Augustus are depicted, where views of the city can be seen. Commissioned by the Conservatori della Comunità (the elected city governors), the frescoes were designed by the humanist Ludovico Castelvetro and executed by Nicolò dell’Abate in 1546. Clearly, the governors, who would meet and vote in this room, chose these specific themes with the purpose of presenting themselves as the “triumvirs”, which refers to any of a group of three officers sharing public administration or civil authority especially in ancient Rome. Also noteworthy in this room is the coffered ceiling, which was made by Giacomo Cavazza and painted by Ludovico Brancolino and Alberto Fontana, as well as the frieze under it, in which triglyphs and metopes alternate and are decorated with motifs of ancient Roman origin.

Now, let’s return to the Chamber of the Confirmed and by crossing it, we will arrive at the Room of the Old Council.

5.3 Room of the Old Council

This room is comparatively small and when the seats of the governors were moved here, it became the council room. The highlight of the room, in my opinion, is the ceiling painting, which is composed of a few sections. In the middle, we see a putto holding a globe and an eagle, which represent the council and the ducal family respectively. Around it, at the four corners are four paintings conveying the ideas of good government and patriotism, two of which were executed by Bartolomeo Schedoni and the other two by Ercole dell’Abate. All of them were painted at the beginning of the 17th century. Around them (above the cornice), there is a series of monochrome scenes which were repainted by Francesco Vellani in 1766 and represent episodes from the life of the patron saint of Modena, St. Geminianus. The seats of the governors, as you can see in the 2nd picture above, were made of carved wood and date back to the 16th century. Resembling classical architecture, the “bench” is divided into many seats by pilasters and topped by an entablature, which is composed of an architrave, frieze, and cornice. Above it, we see a painting depicting St. Geminianus kneeling while pointing to the city of Modena before Our Lady of the Rosary. It was painted by Ludovico Lana to mark the end of a terrible plague in 1630.

5.4 Room of the Tapestries

The name of this room came from the large canvases imitating tapestries, which were completed in 1769 by Girolamo Vannulli (figures) and Francesco Maria Vaccari (decoration). They depict the Peace of Constance, which was signed in 1183 in the city of Konstanz by the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick Barbarossa and representatives of the Italian Lombard League. The agreement granted cities in the Kingdom of Italy local jurisdiction over their territories and freedom to elect their own councils and to enact their own legislation, thus bringing to an end the conflict between the cities of Northern Italy including Modena, and the Holy Roman Empire. If you are interested in furniture, the large mirror above the fireplace, 18th-century armchairs in lacquered wood and 19-century inlaid walnut table are also worth your attention.

5.5 The Wedding Room

This room is the brightest and most spacious among all the five rooms we can visit in Palazzo Comunale and particularly noteworthy are the works by Adeodato Malatesta, the most important Modenese painter of the 19th century. Besides the works depicting historical subjects, his portraits show influences of different schools and introduce to us the prominent individuals and families of the 19th-century Modena.

In this post, I focused on the Ghirlandina Bell Tower (Torre Civica), which is inscribed by the UNESCO as part of the Modena Cathedral Complex World Heritage site. Besides enjoying the great view from the Chamber of the Tower guards, it’s of equal importance to learn about the tower’s history, construction process and decorative elements. The Chamber of the Stolen Bucket houses the replica of the famous bucket stolen from Bologna, whereas the original, a war trophy and civic symbol of the Modenese, is now kept in the Chamber of the Confirmed in Palazzo Comunale. Though located in the buffer zone, it’s interesting to read the town hall’s history and admire its furnitures and decorations, in particular the paintings. In the next post, I’ll take you to Piazza Grande, where the religious and civic lives of the Modenese overlapped in the Middle Ages. What’s more, I’ll show you the Municipal Balsamic Vinegar Factory and introduce to you the Traditional Balsamic Vinegar (TBV), which is produced from cooked grape must, aged at least 12 years, and protected under the European Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) system, and therefore, is much more special and expensive than the normal balsamico we can buy in the supermarkets.