Following my previous post about the Galleria Estense, this post is gonna be about some masterpieces of El Greco, Tintoretto, Veronese and Guercino, as well as some Roman antiquities. Now, let’s get started with the Portable Altarpiece by El Greco (Domenico Theotokopulos).

Portable Altarpiece by El Greco

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (1541 – 1614), most widely known as El Greco (“The Greek”), was a painter, sculptor and architect of the Spanish Renaissance. “El Greco” was a nickname, a reference to his Greek origin, and the artist normally signed his paintings with his full birth name in Greek letters, Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος (Doménikos Theotokópoulos).

El Greco was born in the Kingdom of Candia, which was the official name of Crete during the island’s period as an overseas colony of the Republic of Venice, and the center of Post-Byzantine art. He was trained and became a master before traveling to Venice at the age of 26. In 1570 he moved to Rome, where he opened a workshop and executed a series of works. During his stay in Italy, El Greco enriched his style with elements of Mannerism and of the Venetian Renaissance, taken from a number of great masters of that time, most notably Tintoretto. In 1577, he moved to Toledo, Spain, where he lived and worked until his death. In Toledo, El Greco received several major commissions and produced his best-known paintings.

As I read from Wikipedia, “El Greco has been characterized by modern scholars as an artist so individual that he belongs to no conventional school. He is best known for tortuously elongated figures and often fantastic or phantasmagorical pigmentation, marrying Byzantine traditions with those of Western painting.” In fact, the first time I saw El Greco’s works, I didn’t even notice that he was a painter of the 16th and early 17th century. If you take a look at his “The Disrobing of Christ”, “Laocoön”, “St. Peter and St. Paul”, “Concert of Angels”, “The Visitation” and in particular, “Opening of the Fifth Seal“, don’t you think certain characteristics can be found in many paintings of the 20th century as well? I’m not an art student, but those paintings simply seem, modern, to me. El Greco’s dramatic and expressionistic style wasn’t much accepted by his contemporaries but found appreciation in the 20th century, in particular by Eugène Delacroix, Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso. He is regarded as a forerunner of both Expressionism (an art movement emphasizing the presentation of the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effects in order to evoke moods or ideas) and Cubism (an art movement in which perspective with a single viewpoint was abandoned and use was made of simple geometric shapes, interlocking planes, and, later, collage).

Signed by the artist, this devotional altar is thought to be El Greco’s most outstanding work from his early period in the Kingdom of Candia. The work arrived at the Galleria Estense in 1805, from the collection of the nobleman and pioneering collector Tommaso degli Obizzi at the Castello del Catajo near Padua. The small dimensions of this work are reminiscent of Cretan cabinet-making, while the highly sensitive use of light and color as well as the plastic interpretation (producing three-dimensional effects) of the bodies shows influence from the Venetian School, which indicates that the artist was (gradually) moving away from byzantine artistic practice towards the Western tradition.

What are the episodes depicted on the portable altarpiece then? Please note, the altarpiece is painted on both sides and don’t forget to take a look at the back. I was so excited to see the three depictions on the front (as you can see in the 1st picture above) that I even forgot to check the back (as you can see in the 2nd picture above). Clearly, the front of the left wing renders the Adoration of the Shepherds and its back renders the Annunciation. The front of the right wing renders the Baptism of Christ and its back renders Adam and Eve. The difficult question is, what does the central panel, both the front and back, represent? First, let’s take a look at the back because it’s a bit easier to understand. It shows the theme of Mount Sinai, a mountain in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt that is a possible location of the biblical Mount Sinai, where Moses is believed to have received the Ten Commandments. At the foot of the mountain, we see St. Catherine’s Monastery, which was built between 548 and 565, and is said to be one of the oldest working Christian monasteries in the world. The painting shows pilgrims on the way to the Monastery, and the Mountain as the Road to Heaven. As I learnt from Webgallery of Art, this theme was of Cretan origin, and faithfully repeats a traditional Byzantine model.

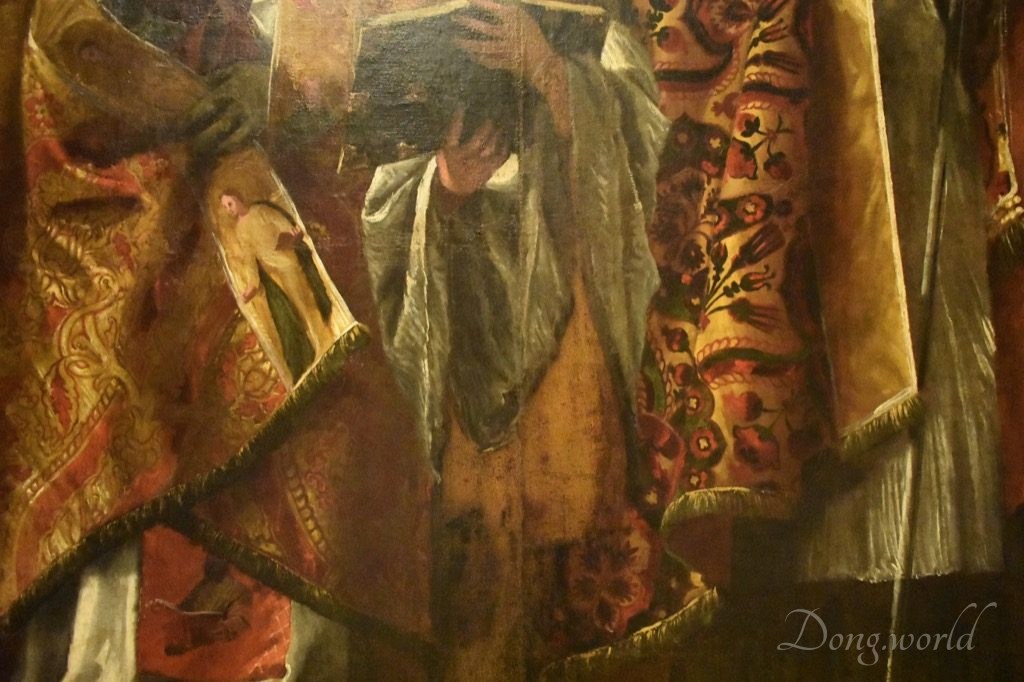

Now, let’s take a close look at the front of the central panel, which in my opinion, is the most sophisticated and beautiful part of the whole altarpiece. It is decorated with the image of the Allegory of the Christian Knight, dominated by the figure of Christ, who is carrying the flag of the Resurrection while stepping on death (the skeleton) and the devil on top of a book. It symbolizes triumph over death and sin. The whole group I mentioned before seems to be held up by the symbols of the Evangelists, that is to say, the angel (the winged man), the bull, the eagle, but where is St. mark the Evangelist, represented by the winged lion? Christ crowns the Christian knight, who has also been interpreted as a prince and even a saint. Above him are two angels, one of which is holding the chalice while the other holding the host (the bread consecrated in the Eucharist). The lower section is dominated by three female figures, one of whom is surrounded by children. On the right side of the women group is the area of the condemned, dominated by Leviathan’s (a sea monster) mouth, while on the left of the women group is the area of the blessed, presided by a bishop who is giving communion. Principally, the scene can be understood as a Last Judgement, which was very common in the Gothic world. It is said on Artehistoria that “this composition seems to have been inspired by a Venetian print while the area of hell was inspired by a painting by Dürer.”

Having said a lot about El Greco and the depictions on the altarpiece, now I’ll finish this section by quoting what’s commented on the official website of the Galleria Estense. “The complex iconography unifies the composition. The Original Sin decreed the Fall of Man, yet humankind’s salvation is made possible through the Incarnation of Christ, narrated in the scenes of the Annunciation and the Adoration of the Shepherds.”

Fourteen panels illustrating Ovid’s Metamorphoses by Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti)

Tintoretto was an Italian painter and one of the most outstanding masters of the Venetian School. The unprecedented boldness of his brushwork was both admired and criticized by his contemporaries. Besides certain characteristics of his works such as the muscular figures, dramatic gestures and bold use of perspective in the Mannerist style, I am most impressed by his mastery over colors and the light and shadow effect, creating (sometimes mysteriously) luminous scenes. Such features can be seen in a series of paintings depicting scenes from the life of St. Mark, exhibited both in the Brera Pinacoteca in Milan and the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. You can read more about them in my posts about the two galleries respectively.

In 1541, sixteen panels illustrating Ovid’s Metamorphoses were commissioned for Tintoretto by the Venetian banker Count Vettore Pisani to decorate a ceiling in Palazzo San Paterniano, Venice, for his marriage to Paolina Foscari. In 1658, they were sold to Duke Francesco I d’Este and were used as ceiling decoration in the Seconda Camera da Parata of the Palazzo Ducale in Modena. Finally, in 1894, they arrived at the Palazzo dei Musei. During the transfer from Venice to Modena, two panels were lost and that’s why you can only see fourteen of them here.

As I learnt from the official website, the composition of these works was influenced by Giulio Romano’s ceiling decoration in the Sala di Psiche at Palazzo Te, Mantua, and a similar use of the di sotto in su (“from below to above”) perspective can be found in the Lombard city. As a series of youthful works by Tintoretto, it already shows the master’s distinctive style, that is to say, the theatricality, exemplified by the characters’ gestures and poses and the dramatic lighting. What’s more, the characteristic chiaroscuro, which makes the figures emerge boldly from the background, and the skillful use of color are another two outstanding qualities of these panels. As commented on the official website “the tonal use of color is typically Venetian whilst its iridescent quality is reminiscent of Michelangelo. The great Florentine master’s influence is also noticeable in the majestic anatomy of the turning bodies and their precarious, agitated contortion.” In fact, if you make a comparison between these panels and Michelangelo’s “Last Judgement”, decoration of the Sistine Chapel ceiling and “Doni Tondo”, it won’t be difficult to find the similarities.

The Metamorphoses is a Latin narrative poem by the Roman poet Ovid. Comprising over 250 myths, the poem records chronologically the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar. Unfortunately, the info board on site was only in Italian and here I try to translate the episodes for you. During my visit, two of the panels were on loan and I hope that during your visit, they will be back “home” already. On the upper level there are 8 panels and they depict the stories of “Jupiter and Europa”, “Mercury and Argus”, “Priapus and Lotis”, “Semele incinerated by Jupiter”, “Deucalion and Pyrrha”, “Race of Hippomenes”, “The massacre of the sons of Niobe” and “Vulcan, Minerva and Cupid”. If you are not familiar with the stories and are interested, below you can take a look at some short explanations which I found in Wikipedia.

Mercury and Argus

Jupiter falls in love with Io, who is the daughter of Inachos, as well as a priestess of Hera. But Jupiter’s wife Hera investigates and finds out about their relationship. Jupiter has to transform Io into a beautiful, white heifer in order to save her from Hera’s wrath and in the meantime transforms himself into a bull. Hera understands his strategy though and demands the heifer as a present. To end their affair, Hera puts Io under the guard of Argus Panoptes, her shepherd, who has 100 eyes. Jupiter commands his son Mercury to set Io free by lulling Argus to sleep with an enchanted flute. Mercury, disguised as a shepherd with a herd of stolen sheep, is invited by Argus to his camp. Mercury charms him with lullabies and then cuts his head off.

Deucalion and Pyrrha

When Zeus decided to end the Bronze Age with the great deluge, Deucalion and his wife, Pyrrha, were the only survivors. Even though he was imprisoned, Prometheus who could see the future and had foreseen the coming of this flood told his son, Deucalion, to build an ark and, thus, they survived.

Race of Hippomenes

In one race Hippomenes was given three of the golden apples of the Hesperides by the goddess Aphrodite. When he dropped them, Atalanta stopped to pick them up and so lost the race.

The massacre of the sons of Niobe

Niobe was punished for her hubris by Leto, who sent Apollo and Artemis to slay all of her children, after which her children lay unburied for nine days while she abstained from food.

On the lower level there are 6 panels and they depict the stories of “Apollo and Daphne”, “Leto transforms the peasants of Lycia into frogs”, “Orpheus implores Pluto”, “The Fall of Phaethon”, “Pyramus and Thisbe” and “Judgement of Midas”. Similarly, if you are not familiar with the stories and are interested, below you can take a look at some short explanations which I found in Wikipedia.

Apollo and Daphne

Apollo had been mocking the God of Love, Cupid. In retaliation, Cupid fired two arrows: a gold arrow that struck Apollo and made him fall in love with Daphne, and a lead arrow that made Daphne hate Apollo. Under the spell of the arrow, Apollo continued to follow Daphne, but she continued to reject him.

Leto transforms the peasants of Lycia into frogs

When Leto was wandering the earth after giving birth to Apollo and Artemis, she attempted to drink water from a pond in Lycia. The peasants there refused to allow her to do so by stirring the mud at the bottom of the pond. Leto turned them into frogs for their inhospitality, forever doomed to swim in the murky waters of ponds and rivers.

Orpheus implores Pluto

The Fall of Phaethon

Phaethon went to his father (Sun-God Phoebus) who swore by the river Styx to give Phaethon anything he would ask for in order to prove his divine sonship. Phaethon wanted to drive the chariot of the sun for a day. Phoebus tried to talk him out of it by telling him that not even Jupiter (the king of the gods) would dare to drive it, as the chariot was fiery hot and the horses breathed out flames. Phaethon was adamant. When the day came, the fierce horses that drew the chariot felt that it was empty because of the lack of the sun-god’s weight and went out of control. Terrified, Phaethon dropped the reins. The horses veered from their course, scorching the earth, burning the vegetation, bringing the blood of the Ethiopians to the surface of their skin and so turning it black, changing much of Africa into desert, drying up rivers and lakes and shrinking the sea. Earth cried out to Jupiter who was forced to intervene by striking Phaethon with a lightning bolt. Like a falling star, Phaethon plunged blazing into the river Eridanos.

Pyramus and Thisbe

Pyramus and Thisbe are two lovers in the city of Babylon who occupy connected houses, forbidden by their parents to be wed, because of their parents’ rivalry. Through a crack in one of the walls, they whisper their love for each other. They arrange to meet near Ninus’ tomb under a mulberry tree and state their feelings for each other. Thisbe arrives first, but upon seeing a lioness with a mouth bloody from a recent kill, she flees, leaving behind her veil. When Pyramus arrives he is horrified at the sight of Thisbe’s veil, assuming that a wild beast has killed her. Pyramus kills himself, falling on his sword in proper Babylonian fashion, and in turn splashing blood on the white mulberry leaves. Pyramus’ blood stains the white mulberry fruits, turning them dark. Thisbe returns, eager to tell Pyramus what had happened to her, but she finds Pyramus’ dead body under the shade of the mulberry tree. Thisbe, after a brief period of mourning, stabs herself with the same sword. In the end, the gods listen to Thisbe’s lament, and forever change the color of the mulberry fruits into the stained color to honour the forbidden love.

Does this story somehow remind you of William Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet”?

Judgement of Midas

Once, Pan had the audacity to compare his music with that of Apollo, and challenged Apollo to a trial of skill. Tmolus, the mountain-god, was chosen as umpire. Pan blew on his pipes and, with his rustic melody, gave great satisfaction to himself and his faithful follower, Midas, who happened to be present. Then Apollo struck the strings of his lyre. Tmolus at once awarded the victory to Apollo, and all but one agreed with the judgment. Midas dissented, and questioned the justice of the award. Apollo would not suffer such a depraved pair of ears any longer, and said “Must have ears of an ass!”, which caused Midas’s ears to become those of a donkey.

In the same room, you can see some other works by Tintoretto and one painting by Jacopo Bassano. Nevertheless, in the next section, I’ll introduce to you in detail one masterpiece by Veronese, who together with Titian and Tintoretto, dominated Venetian painting of the cinquecento.

“Holy Bishops Geminiaus and Severus” by Veronese (Paolo Caliari)

Paolo Caliari, also known as Paolo Veronese, was an Italian Renaissance painter of the Venetian School and he’s among my favorite painters of all time. Although his works are rather widely distributed, for example, I’ve seen them in London, Paris, Florence, Madrid, Verona, Milan, Munich and so on, the most important, or the most impressive ones are in Venice, either in the churches, palazzos or Gallerie dell’Accademia. Also, he is called the leading Venetian painter of ceilings. As commented on Wikipedia, he has always been appreciated for “the chromatic brilliance of his palette, the splendor and sensibility of his brushwork, the aristocratic elegance of his figures, and the magnificence of his spectacle“. For me personally, his dramatic and colorful style as well as the majestic architectural settings are always attractive and enchanting. Known as a supreme colorist, and after an early period with Mannerism, Paolo Veronese developed a naturalist style of painting, influenced by Titian. His own influence is also far-reaching and among his admirers are Rubens, Watteau, Tiepolo, Delacroix and Renoir.

I spotted this painting and guessed it’s Veronese’s work easily not only because of the spectacular color but also because it looked very similar to a painting (“St. Anthony Abbot between Sts. Cornelius and Cyprian”) that I saw in the Brera Pinacoteca in Milan. As for the Brera piece, it is said that “recent restoration has allowed a recovery of the vibrant tone of the original colors, which brought more assurance to the authorship of the painting”. In this regard, you can imagine how unique and successful Veronese’s use of color is.

Originally, the images of Sts. Geminiaus and Severus adorned the two central doors of the organ in the Chiesa di San Geminiano in Venice, built around 1560. Once opened, the backs of these doors were decorated with two smaller canvases, which, as you can see in the picture above, are presently placed on the sides of the central piece. They depict St. Giovanni Battista (on the left) and St. Menas (on the right). In the 18th century, these canvases were removed from the organ and from that moment on, Sts. Geminiaus and Severus have been united in a single painting. Can you see the joint of the two parts? In fact, if you pay attention, you will notice it easily.

After the demolition of the church in 1807, the paintings were transferred to the hands of the Austrian imperial family. In 1836 the painting of Sts. Geminiaus and Severus was added to the Austrian collection along with the painting of St. Giovanni whilst the St. Menas canvas arrived at the Galleria Ducale in Modena. It was in 1919 that the three doors returned to Italy and they arrived at the Galleria Estense in 1924, completing the original set.

As I said about the similar painting in the Brera Pinacoteca, the color, pattern and vivid depiction (such as the folds) of the two saints’ garments and cloaks testify to Veronese’s luminous use of color and mastery over lighting. Even though no halos were painted above the saints’ heads, we still feel they are shining in the apse, adding a sense of holiness to the entire representation.

“St. Roch in Prison” by Guido Reni

Guido Reni was an Italian painter of the high-Baroque style. He painted primarily religious works, as well as mythological and allegorical subjects. Active in Rome, Naples, and his native Bologna, he became the dominant figure in the Bolognese School.

This work was completed between 1617 and 1618 for the Chiesa di San Rocco in Carpi, province of Modena. It was added to the ducal collection in 1751, appropriated by the French at the turn of the century and returned in 1815.

As I read from the official website, this work was produced during the most fruitful period of the artist’s career when he also painted the “Labors of Hercules” for the Duke of Mantua, now exhibited in the Louvre, Paris. After returning to Bologna from Rome, Reni played a leading role in the Bolognese School. “The Saint’s figure embodies the artist’s Christian-inspired vein of naturalism: solemn and majestic he stands out in the perfectly balanced space. Yet each element of color and composition, calculated confidently and with great care, is ultimately elevated by the cold light to an abstract world of musical grace.”

Four oval paintings of mythological figures by Annibale, Agostino and Ludovico Carracci

The four oval paintings (originally there were five but now one is missing) of mythological figures were commissioned for Annibale, Agostino and Ludovico Carracci by Cesare d’Este, who in 1591 decided to refurbish parts of Palazzo dei Diamanti, including his wife’s chamber and the Camera del Poggiolo. The paintings were probably intended for the Camera del Poggiolo, featuring Flora, Galatea, Venus, Pluto and Aeolus (which is the one missing today). In 1592 the works arrived at the Palazzo in Ferrara, staying there until 1630 when Francesco I d’Este ordered the surviving works to be taken to the Palazzo Ducale in Modena. In 1796 they were transferred to France following the Napoleonic appropriation, and only returned to the Este family in 1815.

To be honest, these paintings didn’t attract me that much but they aroused my interested in the three artists, that is to say, Annibale, Agostino and Ludovico Carracci. Why did they share the same family name? Obviously it’s because they were from the same family. Annibale Carracci, probably the most popular among the three, was active in Bologna and later in Rome while his cousin, Ludovico, is said to have created works that reinvigorated Italian art, especially fresco art, which absorbed formalistic Mannerism. In 1582, Annibale, his brother Agostino and his cousin Ludovico opened a painters’ studio and the three of them became forerunners of a leading strand of the Baroque style. As I learnt from Wikipedia, both the typically Florentine linear draftsmanship, exemplified by Raphael and Andrea del Sarto, and the Venetian traditions (such as Titian’s works), which can be seen in the glimmering colors and mistier edges of objects of Carraccis’ works, influenced the three artists and “this eclecticism was to become the defining trait of the artists of the Baroque Emilian or Bolognese School“.

From the info board next to the panels, you can see the attribution of each piece. Though individual stylistic characteristics of each artist can be identified, the paintings share some principle elements, for example, as suggested on the official website, “the di sotto in su spatial composition, the supine position of the bodies, their dynamic, well-rounded forms (reminiscent of Michelangelo’s drawing), and an atmosphere worthy of Correggio.”

Another point I’d like to say here is the comparison between Caravaggio and the Carraccis (mostly Annibale Carracci). For me personally, the former is way more popular than the latter. For example, in many museums or art galleries such as the Louvre, Uffizi Gallery, Brera Pinacoteca, Biblioteca Ambrosiana and so on, we always see Caravaggio’s works in the masterpiece list, but as for the works by Carracci, they don’t usually seem much emphasized. Nevertheless, we might have underrated this Bologna-born artist. As suggested on Wikipedia, Caravaggio almost never worked in fresco, which is regarded as the test of a great painter’s ability. On the other hand, Carracci’s best works are in fresco. “Thus the somber canvases of Caravaggio, with benighted backgrounds, are suited to the contemplative altars, and not to well-lit walls or ceilings.” In this case, it’s not easy to make a fair comparison because they worked and made achievements in, strictly speaking, two different fields. What’s more, the 17th-century critic Giovanni Bellori praised Carracci as the model of Italian painters, who had revived the great tradition of Raphael and Michelangelo. In contrast, though admitting Caravaggio’s talent as a painter, Bellori viewed the Caravagesque style as “gloomy dismay“, probably because of the artist’s ill-famed personality. If you are interested in Caravaggio and his works, you can read my posts about the Biblioteca Ambrosiana and the Brera Pinacoteca.

Venus, Mars and Cupid by Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri)

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, best known as Guercino, was an Italian Baroque painter and draftsman from the region of Emilia, and was active in Rome and Bologna. He acquired the nickname Guercino (squinter) at an early age because he was cross-eyed. The dramatic composition is typical of Guercino’s early works while his later works are closer to the style of his contemporary Guido Reni, and are painted with more lightness and clearness.

This painting was commissioned by Francesco I d’Este and was completed in 1633, during one of the artist’s stays at the court of Modena. At the background, Mars opens the curtain, underlining a sense of sudden interruption while in the front, Cupid, following the indication of Venus, is about to shoot the spectator with his arrow of love. This is a rather traditional but effective way to attract the attention of the viewer. Which part of the painting do you think is the most impressive? For me, it’s the right hand of Venus. It appears to have been painted with the trompe-l’œil technique and looks as if it existed in three dimensions.

Another work by Guercino which attracted my attention in this gallery was the “Mystical marriage of St. Catherine”, but unfortunately, not much information is available about it.

Flora by Carlo Cignani

Young Flora, sprinkled with flowers, is depicted in a sensual and idealized way, which represents a magnificent prototype of the 18th-century grace. Having made a break with the more energetic style of earlier Bolognese classicism of the Bolognese School, Cignani turned towards the ancient lessons of Correggio, creating a style which became successful and popular at many European courts in the 18th century.

After exiting this room, you will be back in the first hall of the gallery. As promised, I’m gonna finish this post by introducing to you two Roman antiquities.

Relief with Aion/Phanes inside the Zodiac

Depicting a young man within a circle made up of twelve zodiac signs, this relief presents the symbols of two originally Eastern religions, that is to say, Mithraism and Orphism. The goat-footed figure himself, wrapped by a coiled serpent and with the heads of a goat, a lion and a ram across his chest, symbolizes the Mithraic god Aion, while his birth, from the cosmic egg in flames and beams of light, is characteristic of the Orphic god, Phanes. At the bottom of the relief you can see two inscriptions, “FELIX” and “PATER”, which are probably the name of the commissioner, who ordered this slab at his expense for votive use in a Mithraeum. The theory, which assumes this relief was made in a Roman workshop, is supported by the high quality of the sculpture.

Spinario

Boy with Thorn, or commonly known as Spinario, is originally a Greco-Roman Hellenistic bronze sculpture of a boy withdrawing a thorn from the sole of his foot, now in the Palazzo dei Conservatori, Rome. During the Roman era, numerous reproductions were made but the Estense version stands out for its quality (fthe other seven or example the highly naturalistic body) and size, being bigger than complete surviving ones (Gallery Estense). What’s more, as I learnt from the website, in a recent study, the work has been traced back to the workshop of the famous Greek sculptor Praxiteles, who was once thought to be the creator of the Venus de Milo in the Louvre Museum.

By now, I have finished my introduction to the Gallery Estense and I hope you have found some artworks that you are interested in. It’s always a nice experience to visit the galleries in different regions and compare the works of difference artists, schools and periods of time. Remember, do not only look into the masterpieces recommended by experts or scholars. Try to find your own favorites. Besides the Gallery Estense, another highlight in Modena is the cathedral complex, which is made up of the Cathedral of Modena, the Torre della Ghirlandina and Piazza Grande, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1997. If you are interested, you can find relevant articles by typing “Modena” in the search bar on the front page.