As the UNESCO comments:

The magnificent 12th-century cathedral at Modena, the work of two great artists (Lanfranco and Wiligelmus), is a supreme example of early Romanesque art. With its piazza and soaring tower, it testifies to the faith of its builders and the power of the Canossa dynasty who commissioned it.

摩德纳的大教堂、市民塔和大广场: 位于摩德纳的宏伟的12世纪大教堂,是兰弗兰科(Lanfranco)和威利盖尔茨(Wiligelmus)这两位伟大艺术家的杰作,是早期罗马风格艺术的最杰出典范。这所大教堂和与之相配套的宏大广场以及耸入云霄的高塔一起,不但证实了建造者们对皇室的无限忠诚,而且还体现了命令建造这些建筑的卡诺萨王朝的非凡国力。

In order to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list, sites must be of outstanding universal value and meet at least one of the ten Criteria for Selection. Modena Cathedral Complex (including Cathedral, Torre Civica and Piazza Grande) meets

Criterion (i) to represent a masterpiece of human creative genius, because the cooperation between Lanfranco (the architect) and Wiligelmo (the sculptor) demonstrated a new dialogue between architecture and sculpture in Romanesque art;

Criterion (ii) to exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design, because the complex influenced greatly the development of Romanesque art in the Po Valley and Wiligelmo’s innovations had profound influence on Italian medieval sculpture. As commented on the World Heritage website, “At the European level, the sculpture of the Cathedral of Modena represents a privileged observatory for the understanding of the cultural context accompanying the revival of monumental stone sculpture. Only very few other monumental complexes, such as Toulouse and Moissac, can claim to be so important in this respect”;

Criterion (iii) to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared, because the busy urban life reflecting the beliefs and values of the citizens in Northern Italy in the 12th and 13th centuries is reflected on the history of the complex including its square and surrounding buildings;

and Criterion (iv) to be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history, because the cathedral, tower and square constitute one of the best examples of an ensemble in a medieval Christian town where civic (economic, political and social) and religious values were combined and both activities (most of the time) were carried out harmoniously.

Attributed to the architect Lanfranco and sculptor Wiligelmo, the magnificent cathedral and its bell tower (Torre Civica), which are consistent in terms of material and structure, are a supreme example of early Romanesque art, renowned for their exceptional architectural and sculptural quality. The foundation stone of the cathedral, home to the mortal remains of St. Geminianus (4th century), patron saint of Modena, was laid on 9th June 1099, replacing an early Christian basilica. The bell tower, whose construction began either together with the cathedral or at the beginning of the 12th century, was originally a five-storey building and was completed in 1319 with an octagonal section and additional decoration. In addition, the property includes the Piazza Grande, which is surrounded by the City Hall, archbishopric, and some other buildings.

Though the exterior of the cathedral and tower appears in general white and a bit yellow during sunset, if you take a close look, you will notice that it’s made of stones of different types and colors. In fact, these areancient Roman stones recycled from Mutina, the Roman Modena. Besides the outstanding values I mentioned above of the complex, there are two other aspects which shouldn’t be neglected. First, these two buildings are a documented example of the reuse of ancient remains, which was common practice in the Middle Ages before quarries were reopened in the 12th and 13th centuries. Secondly, between the 11th and 12th centuries, the cathedral was one of first buildings where collaboration between an architect and a sculptor was recorded by explicit inscription, which can be found on the west façade (as you can see in the 6th picture above). As commented by the UNESCO, “It also marked the shift from a conception of artistic production emphasizing the quality of the buildings as a masterpiece of the munificence of its founder, to a more modern concept in which the role of the creator is recognised.” I still remember when I was watching and reading about the west façade, a local grandma passed by and talked to me in Italian. Sadly I didn’t understand her at all because I don’t speak Italian but I saw she was pointing at the stone plaque and I realized it must be of particular importance. Later I found out why she was so excited about it. That was the first time I experienced the enthusiasm of the Modenese and I’m really glad that the locals are aware and proud of the treasure that they have.

Between the end of the 12th and beginning of the 14th centuries, the cathedral’s and tower’s decorations developed greatly under the influence of the Campionesi masters, who always took into consideration the principles of the post-Wiligelmo Emilian Romanesque School and the innovations of Benedetto Antelami. What’s more, the documented presence of them provides a significant amount of information about how the works were managed on a well-organized medieval construction site.

1. The city of Modena

First, what do you know about this ancient city? For me, besides the cathedral complex, which meets four out of the ten Criteria for Selection although only one is needed to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list, as a food lover, I knew it was famous for its production of balsamic vinegar, and as an opera lover, I knew it was the hometown of Luciano Pavarotti, who was born and died here. If you love cars, in particular sports cars, you probably know already that Modena is also known for its automotive industry since the factories of the famous Italian sports cars such as Ferrari, Lamborghini, and Maserati are, or were, located here, and both Ferrari and Maserati have their headquarters in the city or nearby. However, do you know that Enzo Ferrari, founder of Ferrari, was actually born in Modena and one of Ferrari’s cars, the 360 Modena, was named after the city itself?

Modena is, in my opinion, so Italian because of its “broken” buildings, “dirty” façades and “messy” streets. Please don’t think negatively of those words because without them, Italy wouldn’t be Italy. The city itself isn’t as clean as Zurich or as developed as New York but that’s why it’s lovely and special. It presents traces of history which are reflected on architecture, artworks and public spaces, and allows the curious and respectful minds to have a conversation with it.

2. Visit to the World Heritage site

Inscribed in 1997, this site has been managed and protected properly for more than 2o years. Therefore, its tourism has developed and matured and the visits are very well-organized nowadays. Why do I say so? In fact, this is one of the few cities I’ve been to in Europe where an all-inclusive ticket,which is entirely dedicated to the attractions related to their World Heritage, is available. In Modena, the ticket gives you access to the Ghirlandina Bell Tower (Torre Civica), Cathedral Museums, the historic rooms in Palazzo Comunale and the Municipal Balsamic Vinegar Factory and it only costs 6 euros per person. On the ticket, you can see the opening hours of the attractions. Please note, if you are visiting Modena on some bank holiday in Italy, I recommend you checking the news and events on the official website because adjusted opening hours may apply. The cathedral is not listed on the ticket because it can be visited free of charge. It’s open every day from 7:00 to 12:30 and from 15:30 to 19:00, but visits are not allowed during religious services or on Sunday mornings.

Unfortunately, during my visit the interior of the cathedral was under restoration, but I visited the crypt and saw most of the artworks in the nave and aisles. In three posts, I’ll give you a detailed introduction to the property as well as some buildings in the buffer zone. The first post will be about the cathedral and Cathedral Museums, the second will be about the bell tower and the historic rooms in Palazzo Comunale, and the third will be about Piazza Grande and the Municipal Balsamic Vinegar Factory.

3. Modena Cathedral

9th June 1099 was an important day in Modena because that’s when the construction of its cathedral began. Normally it’s not easy to find out when exactly a building, which is more than 900 years old, started to be built, but here, thanks to the preservation of a historic document called “Relatio“, a 13th-century text recording the construction process of the cathedral, we gained much information about the development of the masterpiece. The document also reported that the choice of the architect, Lanfranco, was miraculously inspired by God. He conceived an innovative and daring design and inspired Romanesque art in the province. For example, echoes of the structure and decorative scheme of the Cathedral of Modena can be seen in many religious buildings in Carpi, Nonantola, San Cesario sul Panaro and in the Apennines. Equally important and spectacular are the decorations devised and executed by Wiligelmo featuring plants, animals, human and imaginary creatures, which can be found on the façade and on the capitals of the loggias, half columns and ledges.

In this chapter, I’ll introduce to you in detail the cathedral including its west, north and south façades and its interior. In accordance with tradition of that time, the church was built in east-west direction and in my opinion, the west façade is the most spectacular, on which many sculptures were created by the master Wiligelmo himself.

3.1 The exterior

3.1.1 The west façade

The upper part of the west façade is dominated by the great rose window, divided into 24 panels and attributed to Anselmo da Campione (13th century). Above it, we see the enthroned Christ in an almond-shaped frame, which was a common depiction of Christ in Majesty in early medieval and Romanesque art, as well as Byzantine art of the same periods. This is considered to be a work of the Campionesi masters while the symbols of the four Evangelists (winged man, winged lion, winged ox and eagle) around it are attributed to the school of Wiligelmo.

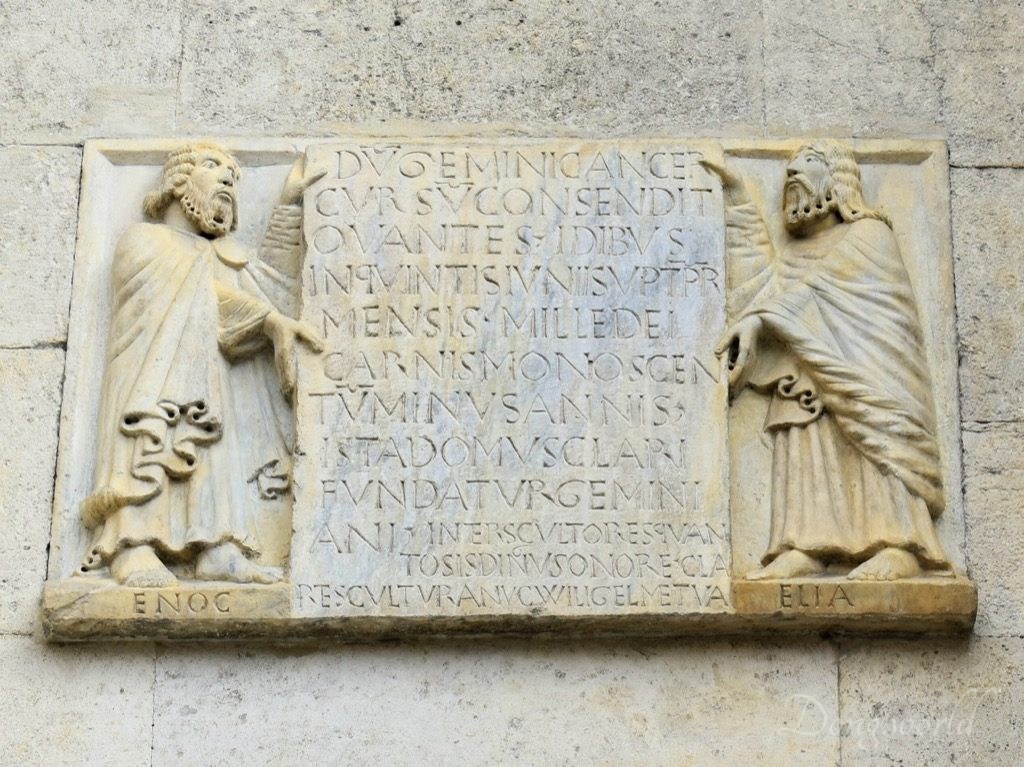

Under the loggia, we see a stone plaque (to the left of the portal) sculpted by Wiligelmo and supported by Prophets Enoch and Elijah. It reads in Latin: 23rd May, 1099, beginning of construction; 9th June, placement of the first stone, and commemorates the creator of the sculptural work. Above the plaque, we see an angel leaning on an upside-down torch followed by an ibis, which can also be found to the right of the main portal, but without the animal.

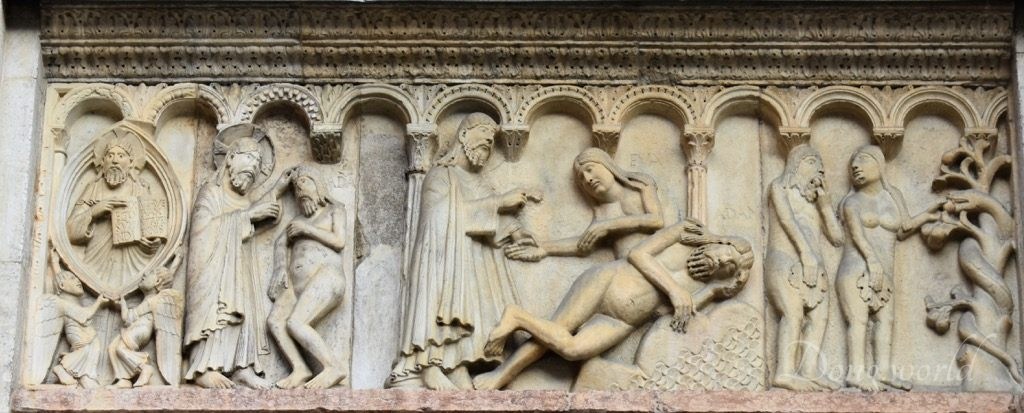

The four large reliefs on the façade, which remain unchanged for more than nine centuries, are Wiligelmo’s principle contribution and are particularly important. Remember, in the early Middle Ages, not many people could read and these illustrations with strong narrative force helped them understand what happens in the Book of Genesis. All the episodes convey the ideas of sin, repentance, fear, hope, faith, redemption and salvation.

- The first sculpture represents the Creation of Adam and Eve and the Original Sin (Adam and Eve eating the apple offered by the snake while covering themselves in fig leaves).

- The second sculpture shows Adam and Eve disapproved by God, driven away from the Eden by an angel and undertaking hard labor because of their sin.

- The third sculpture shows Cain and Abel, Adam and Eve’s first children, offering a lamb and ears of corn to God, Cain killing Abel and God questioning Cain.

- The fourth sculpture shows Cain killed by Lamech with his eyes closed, a sixth-generation descendant of Cain, Noah’s Ark during the Flood, which was modeled on the cathedral aiming at delivering the message that through the church can salvation be achieved, and Noah and his sons disembarking from the Ark.

The main portal, which serves as a symbolic screen between the faithful, who gather inside, and the outsiders, who may fall prey to the devil, was decorated by Wiligelmo himself. The column-bearing lions were probably taken from an ancient grave. The extrados is sculpted with rich sprays, in which human, natural and peculiar figures such as basilisk, mermaid, griffin, vipers, hawk, and crane are hidden. In the intrados, twelve prophets related to the prophecy of the coming of Christ as savior of the world were selected. Their names can be seen in the respective niches. Under the archivolt, we see the head of an old man in the middle of the lintel. It represents Janus, the Roman god of gates and doorways. On the projecting part of the main portal, which you can see in the 1st picture above, two deer are wrestling with a shared head and two lions are trying to break free from a snake, symbol of the fight of mankind against sin.

3.1.2 The south façade

On the southern side of the church, we first see the Porta dei Principi (Portal of Princes), which was modeled on the main portal and attributed to a contemporary follower of Wiligelmo. The extrados was decorated with inhabited sprays but in the intrados, twelve apostles with Matthias replacing Judas the betrayer instead of twelve prophets were sculpted. On the front of the lintel, episodes from the life of St. Geminianus are depicted. He sets off to the East by riding a horse and then by boat to exorcise Emperor Jovian’s daughter (a winged demon can be seen) and after receiving gifts, he returns to Modena, where he dies and is buried like a mummy. On the bottom of the lintel, we see a lamb held up by two angels and looked upon by St. John the Baptist and St. Paul. It is said that through this portal entered the people who had faith in Christ and in the Church and were ready to be baptized.

If you keep walking towards east along the church, you will soon see an inscription commemorating the consecration of the Cathedral of Modena by Pope Lucius III on 12th July, 1184.

Next to the inscription, Porta Regia (Royal Portal) stands out on Piazza Grande not only because it projects out of the façade but also because of its color. Attributed to the Campionesi masters (13th century), this is in my opinion the most beautiful portal of the church. The rose-colored Veronese marble alternate with carved pillars, conveying a feeling of warmth and elegance. Two of the columns are supported by lions with prey under their paws, which are similar to the ones lying on the steps leading to the crypt inside the cathedral, while the other eight, which are thinner and divided into two sets, are interwoven, evoking a sense of lightness and movement. In the niche above the portal, we see the statue of St. Geminianus (the original one is now preserved in the Cathedral Museum), and next to it, a bone of a whale.

After passing Porta Regia, we see a pulpit created in 1501 by Jacopo and Paolo da Ferrara, with symbols of the four Evangelists. Close to the apses, there is a relief divided into four parts depicting four episodes from the life of St. Geminianus. In addition to the stories which are the same as those represented on Porta dei Principi (Portal of Princes), it also includes the scene of the miracle of the frog which saved Modena from the barbarians. It was created in 1442 by Agostino di Duccio but only placed on the cathedral in 1584.

3.1.3 The apses

The apses (back of the cathedral) are in my opinion the best place to admire the twenty different kinds of recycled stones covering the cathedral. On the central one, a plaque commemorates the architect and surmounts a window adorned with sculpted flowers.

3.1.4 The north façade

On the north façade, the Porta della Pescheria (Fishmarket Portal), created by the Wiligelmo School, is the most interesting and curious. As its name suggests, once a fishmarket stood close by. Similar to the other portals, it’s characterized by two column-bearing lions and its extrados features inhabited sprays held by two telamones. In the intrados, twelve months of the year are vividly represented. For example, January preserves a pig, March cuts the grapevines, April brings flowers, June cuts the grass with a sickle, July reaps the wheat, September makes wine, and December cuts the wood. I recognized most of the months because the names sculpted in the niches are similar to those in English, but even if you can’t read, based on the lively images, you can more or less guess which season each scene depicts.

On the architrave, four fables are depicted. The second one shows two cocks bringing in a fox pretending to be dead, the third shows two storks trying to free themselves from a snake and the fourth shows a wolf and a crane. Particularly noteworthy is the story represented on the archivolt, in the middle of which “Winlogee“, presumably Guinevere, can be seen imprisoned in a castle by “Mardoc“. The knights including King Arthur and Gawain, are trying to free her. As the caption suggests, this is a story of the Arthurian Legend. An interesting thing is that Arthur was first identified as a fictional high king by Geoffrey of Monmouth, who defined in Latin the first coherent version of the Arthurian Legend in his Historia Regum Britanniae, in which Guinevere first appears. The book was written in around 1136, but the portal was created twenty years before, which makes this archivolt the most ancient representation of the story in the world.

3.2 The interior

The interior of the cathedral, divided into a nave and two aisles, evokes an entirely different feeling because it’s mostly built in brick except for the marble pillars. It looks much darker than the exterior and feels more serious and powerful. The marble pillars and brick columns alternate and at middle level, fake woman’s gallery can be spotted, which were never realized. Even higher, several large windows give light to the inside. There are several highlights in the church and now I’ll show them to you one by one.

In front of the central apse and above the entrance to the crypt, we find an ambo and a balustrade, which were sculpted and painted between the 12th and 13th centuries by the Campionesi masters. On the ambo, to the left of the enthroned Christ, we see symbols of Evangelists Mark and Matthew; four doctors of the Church; Sts. Geronimo and Ambrose; and Sts. Augustine and Gregory the Great. To his right we see symbols of Evangelists John and Luke; and Jesus awakening his disciples in Gethsemane, an urban garden at the foot of the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. On the balustrade, from left to right we see Jesus washing the Apostles’ feet; the Last Supper with Jesus giving a morsel of food to Judas; the Kiss of Judas; Jesus before Pontius Pilate and the Flagellation; and Simon of Cyrene carrying the Cross.

In the south aisle, we can admire the Bellencini Chapel, in which the Last Judgement was painted by Cristoforo da Lendinara in the 15th century. Pay attention to the half-naked men at the bottom, the saints, and the angel holding a sword and a pair of scales. In front of the chapel stands an elegant baptismal font in red marble. On our way to the south apse, a crib (a model of the Nativity of Christ) in terra-cotta by Antonio Begarelli (1527) can be seen and before ascending, don’t forget to touch the smooth marble handrail which finishes with the head of a lion.

In the north aisle, the most important pieces are the Altar of St. Catherine, a polyptych entirely carved in terra-cotta by Michele da Firenze between 1440 and 1441, and the polyptych called “Tela del Dosso Dossi” (16th century), which was painted by the famous artist Dosso Dossi depicting St. Sebastian and other saints. Sadly, as I mentioned above, during my visit the church was under restoration and most of the north aisle was inaccessible. Therefore, I didn’t see the two polyptychs. Fortunately, the crypt was all open, which is the resting place of the patron saint of Modena, St. Geminianus, and now I’ll take you there to have a look.

Before descending, let’s take a look at the “supporters” of the gallery and ambo which were decorated by the Campionesi masters. Four columns are supported by four lions, one of which is bitten by its prey, one traps a dog and the middle two are clawing at knights with armor. Two other columns which support the ambo are carried by two telamones, whose position and facial expression indicate the pain of hard work. The interior of the crypt is featured with a forest of columns, some of which were recycled and are said to precede the work of Wiligelmo. Compared to the nave and side aisles, this is a more intimate space, which brings the devotees closer to the patron saint, and then God himself. In the central apse, St. Geminianus’ sarcophagus is visible inside a transparent shrine and is supported by several short columns. It is said that in the past, they allowed the faithful to pass under as a sign of devotion. In the right apse, polychrome terra-cotta figures were created by Guido Mazzoni (15th century) representing the Holy Family and in the left one, a crucifix and a golden urn can be seen.

By now, I’ve finished introducing in detail the cathedral and I hope when you visit it, you will feel better oriented. I heard that it would be possible to visit the raised north and central apses once the restoration was finished and in them, you’ll find some more artworks to admire. Now, we will move to the nearby Cathedral Museums, which are closely related to the Cathedral of Modena and its liturgical services.

4. Cathedral Museums

Admission to the Cathedral Museums is included in the all-inclusive ticket and at the reception, don’t forget to ask for a free booklet which introduces not only the collections of the museum but also the cathedral itself, accompanied by pictures. The lady at the front desk was super nice because there was no introduction in English to the Lapidary Museum, which is part of the Cathedral Museums, and she pointed out what the most curious and important pieces are and gave me some explanations. Now, let’s start with the Lapidary Museum, which occupies two rooms on the ground floor.

4.1 Lapidary Museum

This museum exhibits sculptures and reliefs from the Roman era, fragments related to the previous early-medieval basilica as well as ancient, medieval and modern inscriptions. The most interesting pieces are exhibited in the second room, which is dedicated to sculpture from the days of Wiligelmo and the Campionesi masters. Particularly worth noting are the eight metopes (as you can see in the pictures above), which were originally located on the buttresses of the cathedral’s roof and were moved here in the 1950s due to conservation problems. Nowadays, the ones you see on top of the cathedral are replicas. All of them were created by a master from the workshop of Wiligelmo and portray various monstrous and imaginary beings taking up peculiar activities. Scholars have been trying to decipher the hidden messages in these metopes and much information was provided on the info sheets on site. Unfortunately, they were only in Italian. I hope the English version would be available soon so that more people could gain some insights into this fantastic world. These creatures somehow reminded me of those in the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shan Hai Jing in Chinese), a Chinese classic text and a compilation of mythic geography and myth. Also in this room, you can see a column-bearing lion from Porta dei Principi (Portal of Princes), which was removed and replaced by a copy due to the damage it suffered during the Second World War.

4.2 Cathedral Museum

This museum was opened in 2000 on the occasion of the Great Jubilee and it displays precious liturgical and artistic items including ornaments, sculptures, reliquaries, fabrics, paintings and codices dating from the Roman period to the 19th century. They are witnesses to the devotion of the faithful Modenese, who, whether poor or rich, made every sacrifice necessary to contribute to the splendor of their cathedral and dignity of the burial place of their patron saint. In the booklet, a lot of information is provided about the collections, but the rooms seem to have been rearranged and suggested locations of the items are not always accurate. Anyway, I’ll introduce some of them here and I believe they are easy to spot as long as you finish visiting all the rooms.

From the early days of Christianity to the end of the Middle Ages, priests, bishops and monks often traveled for missionary purposes. In order to perform the sacred celebrations along the way, they used to carry portable altars, which were essentially consecrated small marble tables. When they died, the altars were buried with them. The Romanesque portable altar shown above is said to be of St. Geminianus and at the beginning of the 12th century, at the request of Matilda of Tuscany, the green serpentine stone was embellished with an engraved silver and beaten gold frame, on which images of the Virgin Mary, the Apostles and St. Geminianus can be seen. In the book about the altar of St. Geminianus by Enrichetta Cecchi Gattolin, an expert on European altars, there is documented evidence suggesting that the sacred stone was used by the bishop during journeys for evangelization and was placed with his remains in his urn. When the tomb of St. Geminianus was opened in 1106, “the Great Countess” Matilda had the stone decorated as a relic of the saint.

Do you remember I mentioned that in the niche above Porta Regia (Royal Portal) there was a statue of St. Geminianus overlooking Piazza Grande? That is a copy and the original is now preserved in the museum. Made of beaten copper, it is the work by Geminiano Paruoli dating from 1376. In the background, the representation of the twelve months of the year is very interesting. Similar to those in the intrados of Porta della Pescheria (Fishmarket Portal), each month is depicted based on its traditional agricultural work.

This reliquary cross is of Byzantine manufacture and dates from the early years of the 11th century. Decorated with gold and pearls, possibly it was already present in the cathedral during its foundation.

A 12th-century Evangeliary (a liturgical book containing only those portions of the four gospels which are read during Mass or in other public offices of the Church) bound in silver and ivory

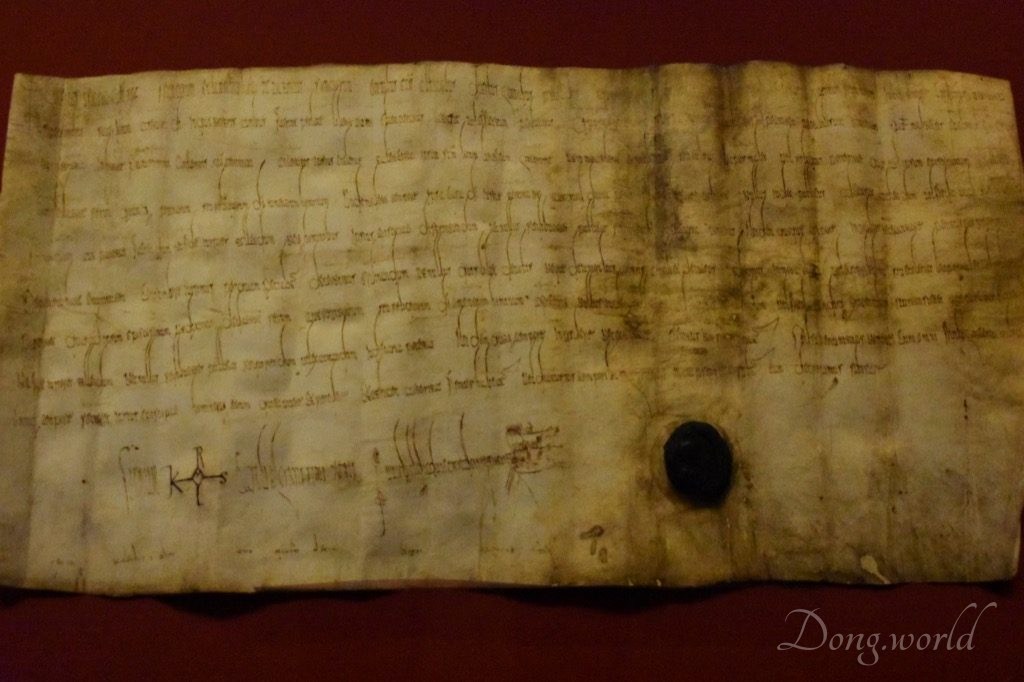

The famous “Relatio“, the oldest codex about the foundation of the cathedral documenting its construction process. Some sources say that it dates back to the 12th century but on the info board on site, it is written that it’s from the 13th.

In this room, you will see St. Geminianus’ rich array of vestments, among which two dalmatics and a chasuble (as you can see in the picture above) embroidered with biblical scenes by the Modenese nuns (18th century) and the alb of Cardinal Ippolito d’Este (as you can see in the picture above) with 17th-century Venetian lacework are the most eye-catching.

Many reliquaries are exhibited in the museum and the two that I found the most interesting were the 18th-century reliquary of Mary Magdalene of Emilian manufacture with reliefs depicting her repentance and meditation and the 18th-century reliquary of St. John the Baptist of Venetian manufacture.

In the room dedicated to the ancient codices and parchments of the Capitular Archive, we can see decrees of Charlemagne (facsimile).

Besides the treasures I mentioned above, there are some others which are equally important. For example, the painting of St. Geminianus by Bartolomeo Schedoni, the chalice known as St. Geminianus’ Chalice (1400), two arrases showing stories from the Book of Genesis, woven in Brussels in the mid-16th century, the 11th-century gold staurotheke, and the Byzantine cross which came from Constantinople during the Crusades.

In this post, besides explaining to you why the Cathedral Complex of Modena meets four out of the ten Criteria for Selection although only one is needed to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list, I focused on the protagonist, that is to say, the magnificent cathedral itself. Additionally, I highlighted some objects in the Cathedral Museums which were either very interesting to me or emphasized in the booklet, so that you can have a clearer idea of the influence of religion and faith on the Modenese. In the next post, I’ll focus on the Ghirlandina Bell Tower (Torre Civica), which was originally a five-storey building designed by Lanfranco and was completed in 1319 with an octagonal section and additional decoration by the Campionesi masters. What’s more, I’ll take you to the historic rooms of the City Hall (Palazzo Comunale), where the famous bucket, which provoked the war between the rival city-states of Bologna and Modena, is now preserved.