Sometimes people ask me why I like paintings in particular those of the Old Masters. There are a few reasons. I like the stories they tell; I like the stories behind their creators; and most importantly, I like how the artists tried to establish a connection between their works and the viewers, which won’t change in hundreds or even thousands of years. Have you ever been touched by a painting? Has there ever been a painting which made you linger? If yes, you can consider yourself lucky because not everyone has the gift to communicate with the masters.

As a big fan of the Italian Renaissance, of Florence and of the Medici family, I travelled to the Alte Pinakothek in Munich especially for the temporary exhibition “Florence and Its Painters – from Giotto to Leonardo da Vinci” ( ‐ . As introduced on the official website, the show with around 120 masterpieces including paintings, sculptures and drawings focuses “on the artists’ world of ideas and working methods” and “presents the groundbreaking artistic innovations at the birthplace of the Renaissance”. The secular pictorial narratives, portraits, and images of private and ecclesiastical devotion “provide a detailed insight into the work methods of Florentine painters and explain the close relationship between technical and stylistic change“.

This is one of the most popular exhibitions I’ve ever been to and there was almost always a line in front of the entrance. In this post, I’ll first explain why this exhibition has been attracting numerous visitors and then I’ll focus on the most impressive works, some of which were transported from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and even from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Highlights:

- The exhibition is well-organised and the information written on the walls introduces artistic developments in Florence from the 14th to the 15th centuries. The sections focusing on the painting techniques and restoration methods were the most interesting for me.

- In each section, a specific theme is explained accompanied by outstanding examples. All the themes are interconnected which show a full picture of the art history of the Quattrocento in Florence, the birthplace of the Italian Renaissance.

- Masterpieces including sculptures, paintings and drawings by Giotto, Fra Filippo Lippi, Antonio Pollaiuolo, Donatello, Andrea del Verrocchio, Lorenzo di Credi, Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, etc. are selected. Some of them are among the collections of the Alte Pinakothek while others were transported from other galleries such as the Uffizi in Florence and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. It’s a unique experience to see how paintings such as altarpieces distributed to different locations all over the world are brought back together.

Now, I’ll introduce some of the masterpieces I saw during the exhibition.

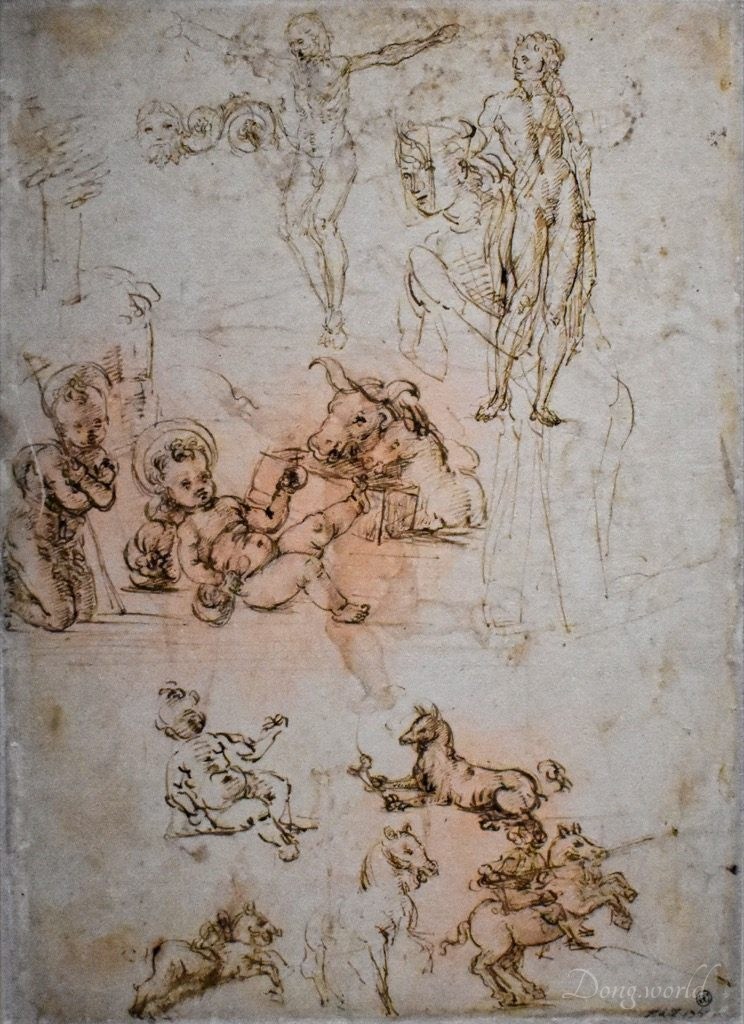

1. Drawing

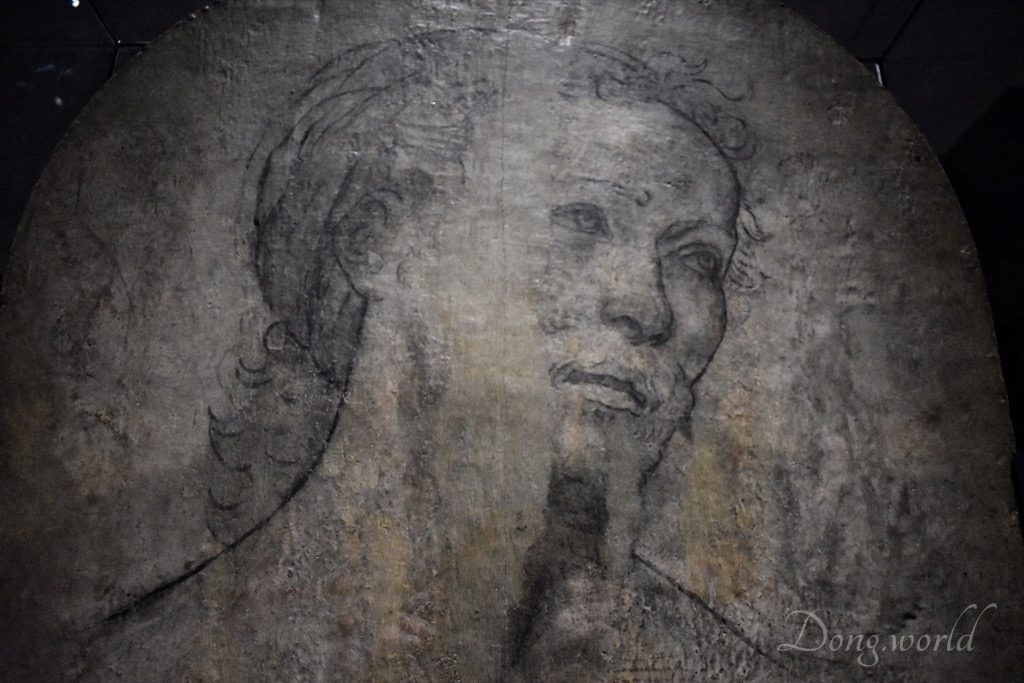

Drawing was of the greatest importance in the training of Florentine artists and accompanied all their work as a central element in the creative process. Apprentices mainly practiced by imitating drawings by their masters and fellow pupils and copying exemplary images. In this way, they soon internalised their workshop’s style. In addition, they made drawings based on pattern books which largely comprised depictions of people, animals and architectural details. In the 15th century, drawing from Antiquity and nature became popular and consequently, sculptures and life models become an indispensable part in teaching. The primary aim was to capture the human body at rest and in motion, clothed or nude. Landscape studies on the other hand were rare.

Drawing was essential in the preparation of a work as artists recorded their creative flow of ideas during the conceptual stage. Afterwards, they progressed from the general idea of their composition to individual details and from the outline to the modelling of light and shadow. As written on the info board, “they sketched and varied the structure of the picture, the constellations and postures of the figures as well as their relation to the pictorial space, and resolved motifs of movement and anatomical details, gestures and facial expressions or the arrangement of drapery folds”. As you can see from the pictures above, from Sandro Botticelli to Leonardo da Vinci, all the masters used drawing as a means of practising when they were young and later a way of conceiving their masterpieces. In some cases, the drafts are so fine that they themselves become much admired. The best examples I’ve seen are the codices containing drawings and writings by da Vinci and Raphael’s preparatory cartoons for “The School of Athens”.

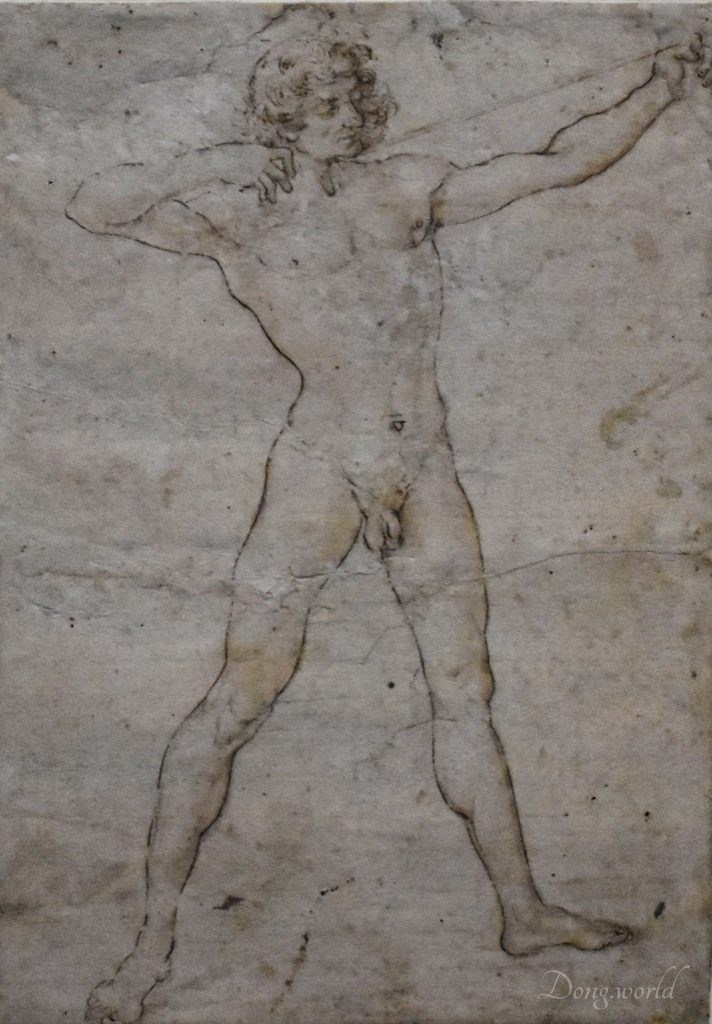

2. Sculpture and engraving

Filippo Brunelleschi, builder of the dome of Florence Cathedral, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Donatello led Florentine sculpture away from the international Gothic style to completely new forms of representation that were to become exemplary for painters. Ghiberti proudly stated that he had modelled the gilded bronze reliefs of his “Gates of Paradise” for the baptistery as faithful as possible on nature and observed the laws of perspective. Both in his narrative reliefs and monumental statues, Donatello modelled sculptures on works of Antiquity but at the same time added realistic elements such as the body and emotions of human being. After establishing his position as an outstanding marble sculptor, he devoted his attention to bronze sculpture. The putti Donatello created in 1429 for the font in Siena’s baptistery, inspired by the Erotes of Antiquity, were conceptually limited both architecturally and in terms of Christian iconography. However, they are the first prototypes that paved the way for the classical-style, free-standing nude figures of the Renaissance.

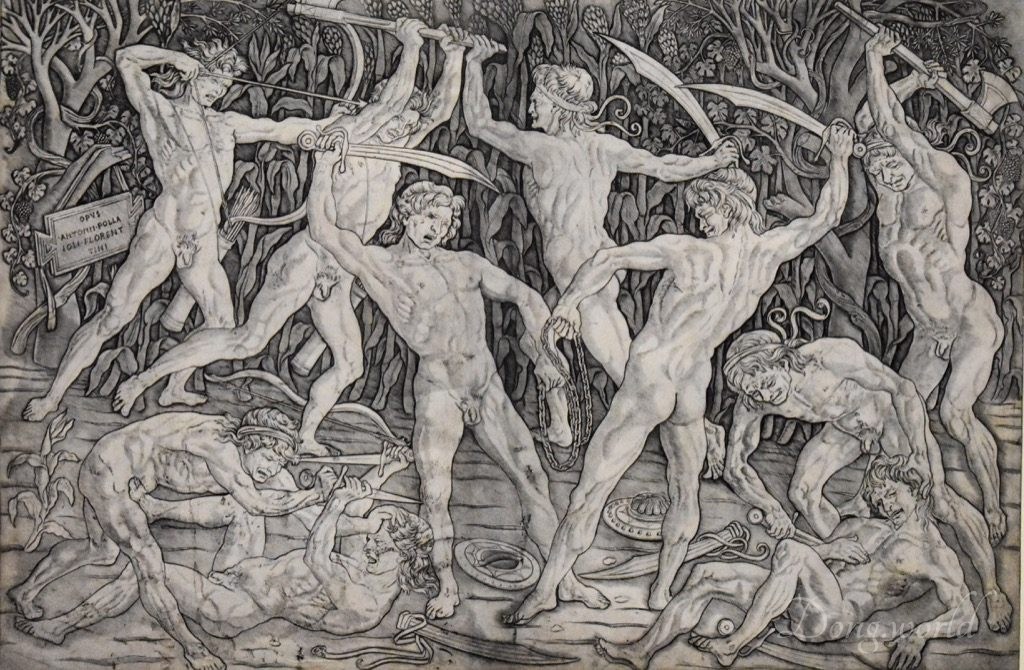

Antonio Pollaiuolo was a painter, sculptor, engraver and goldsmith during the Italian Renaissance, whose main contribution to Florentine painting lay in his analysis of the human body in movement or under conditions of strain, but he is also important for his pioneering interest in landscape. His students included Sandro Botticelli. He only produced one surviving engraving, “The Battle of the Nude Men”, which both in its size and sophistication took the Italian print to new levels, and remains one of the most famous prints of the Quattrocento. Luckily, I saw one of the surviving impressions in this exhibition.

The engraving is large (42.4 x 60.9 cm) and depicts five men wearing headbands and five men without, fighting in pairs with weapons in front of a dense background of vegetation. All the figures are posed in different strained and athletic positions, whose fierce grimace and emphasised musculature made the print advanced for the period. The two figures in the middle are essentially in the same pose, seen from in front and behind, and it leads to the assumption that one purpose of the print may have been to give artists poses to copy.

What do you think of the print? Do you like it? As I read from Wikipedia, Giorgio Vasari spoke highly of Pollaiuolo and wrote that: “He had a more modern grasp of the nude than the masters who preceded him, and he dissected many bodies to study their anatomy; and he was the first to demonstrate the method of searching out the muscles, in order that they might have their due form and place in his figures; and of those … he engraved a battle.” Nevertheless, it has been suggested that Leonardo da Vinci may have had Pollaiuolo partly in mind when he wrote that artists should not: “make their nudes wooden and without grace, so that they seem to look like a sack of nuts rather than the surface of a human being, or indeed a bundle of radishes rather than muscular nudes.” Regarding artistic development, the expressions of facial features and anatomy are indeed inspiring but personally, I feel the emphasis might be too strong and the print itself is probably more real than beautiful.

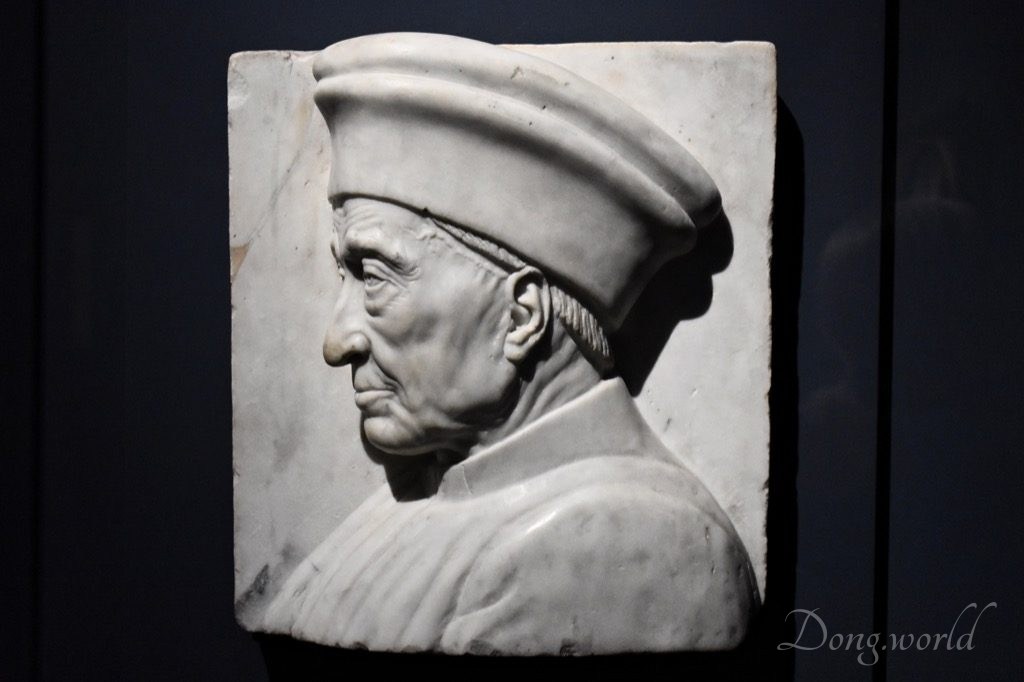

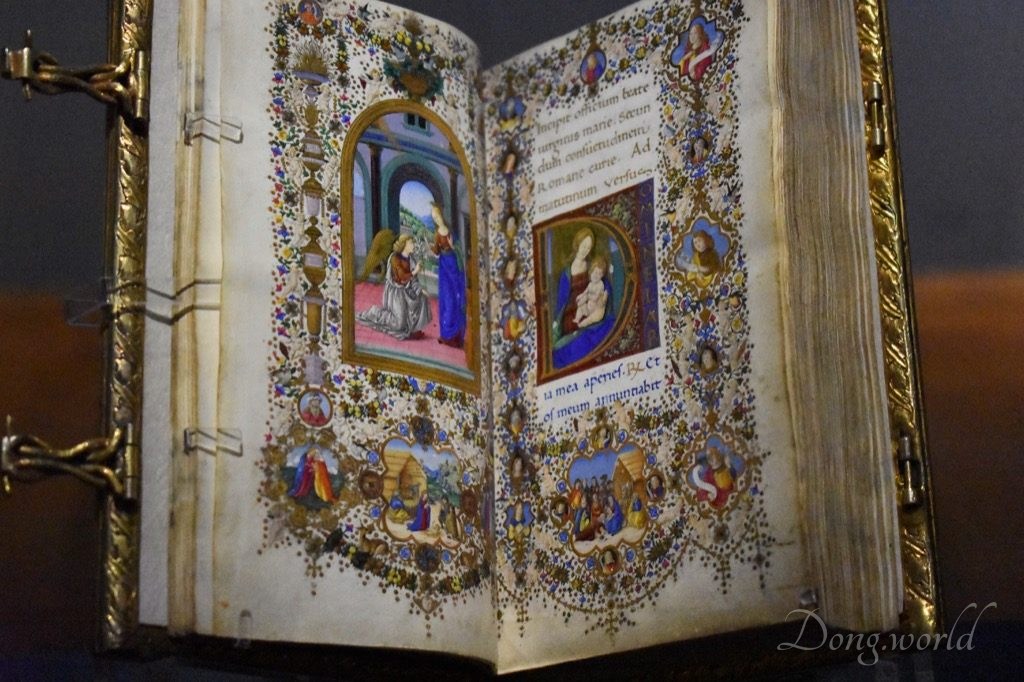

Talking about the Renaissance and Florence, how can we ignore the Medici family? In this exhibition, I saw a relief of Cosimo de’ Medici by Antonio Rossellino and workshop, who was an Italian banker and politician and the first member of the Medici political dynasty that served as de facto rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance. His power derived from his wealth as a banker and he was a great patron of learning, the arts and architecture. Due to the resemblance between the sculptural portrait by Antonio Rossellino and the painted portrait by Bronzino, it’s possible that the latter was modelled on the former. Another eye-catching piece among the exhibits is “Lucrezia de’ Medici’s Book of Hours“, which was elaborately illuminated by Francesco Rosselli and Gherardo di Giovanni. A book of hours is a Christian devotional book popular in the Middle Ages and like every manuscript, each book is unique in one way or another, but most contain a similar collection of texts, prayers and psalms, often accompanied by appropriate decorations. I still remember when I was looking closely at the open pages, every passer-by wowed with astonishment and admiration. Can you imagine how much time and effort it took to create such intricate illumination for the whole book?

3. Painting (tempera and oil)

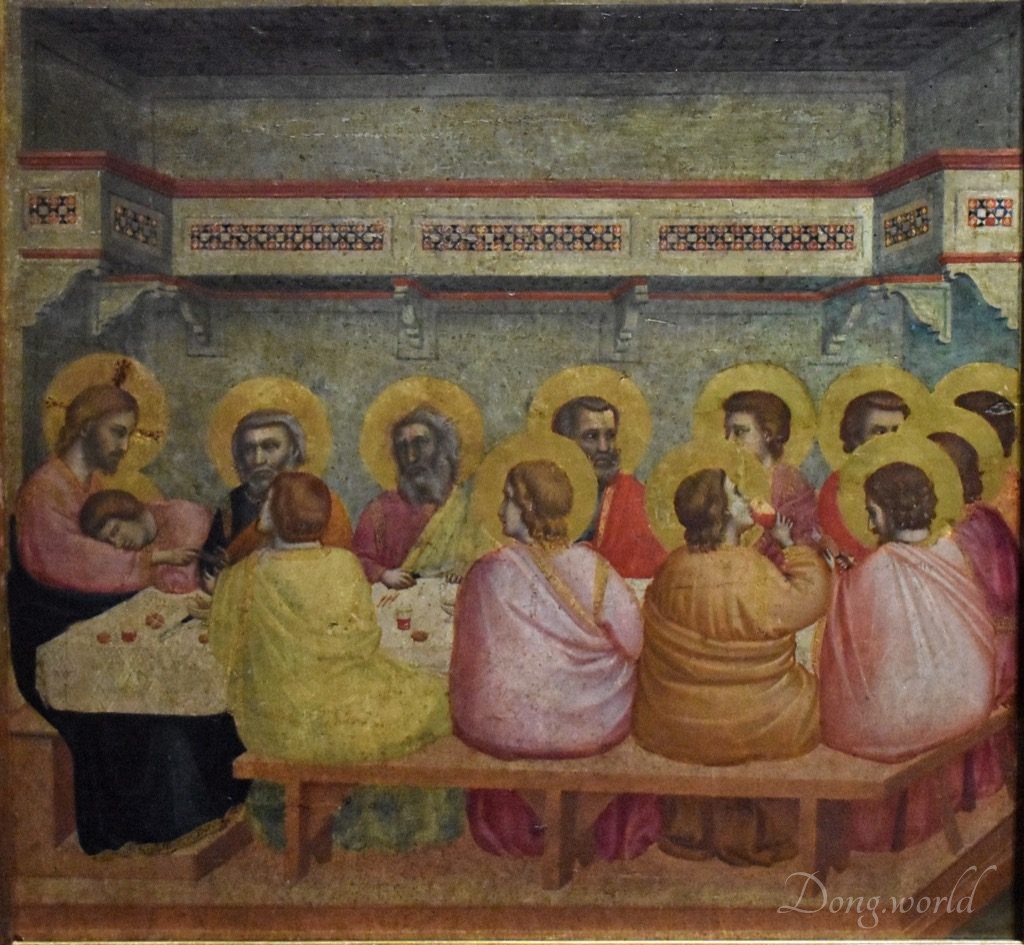

Three altar panels by Giotto

The three altar panels depicting “The Last Supper”, “Christ on the Cross” and “Christ in Limbo” are among the permanent collections of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich so you can still see then here after the exhibition finishes. Giotto was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages, who worked during the Gothic and Proto-Renaissance periods. I first noticed the artist during my visit to Palais Rohan in Strasbourg when I saw one of his panels depicting the Crucification of Christ. In that painting, figures in the background appear smaller which indicates distance and the feeling of pain can clearly be seen on Jesus’ face, which marks the his transition from the God to human in artistic representations. It’s actually an important change for the faithful as they feel that the God they believe in share sympathy with them.

Giotto’s contemporary, the banker and chronicler Giovanni Villani, wrote that Giotto was “the most sovereign master of painting in his time, who drew all his figures and their postures according to nature“. In his “Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects”, Giorgio Vasari described Giotto as making a decisive break with the then widespread Byzantine style and as initiating “the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than two hundred years”. As you can see in the “Last Supper” above, the meaning of the painting is conveyed by the apostles’ and Jesus’ gestures, facial expressions and movements.

Tondo by Master of Santa Lucia sul Prato

In Italian art, the transition from tempera to oil took place in the 15th century, which didn’t happen abruptly but over a long period. The choice between egg and oil was made by every painter individually either out of habit or experience or for reasons of efficiency. The potential of the new technique was particularly evident in the possibility it offered to create continuous colour transitions as through oil’s long drying time, the colours could be worked into one another on the surface of a painting, wet in wet, and a fluent chromaticity could be achieved. What’s more, it made the modelling of three-dimensional volumes and generation of light and shade possible. The tondo shown above by the circle of the Master of Santa Lucia sul Prato is one of the best examples demonstrating the specific effects of the oil technique. At first, I was attracted by its bright colours and after taking a close look, I noticed that the details such as the gleaming dark marble columns, the shimmer of the Virgin’s dark-green gown and the soft modelling of the flesh tones are simply stunning.

Madonna of Palazzo Medici-Riccardi by Filippo Lippi

Born in Florence in 1406, Fra Filippo Lippi, also called Lippo Lippi, was an Italian painter of the Quattrocento. Francesco di Pesello (called Pesellino) and Sandro Botticelli were among his most distinguished pupils. In this exhibition, I saw one of his masterpieces depicting the Virgin and Child, which was transported here from Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence.

The painting was found by art historian Giuseppe Poggi in 1907 in the psychiatric hospital of San Salvi in Florence. There are several theories about the origin of the panel. Poggi assigned it to the Villa of Castelpulci, owned by the Riccardi family, who bought Palazzo Medici in 1655 while according to another, the Madonna was instead part of the original decoration of the palace. After having been acquired by the Italian state, it was moved to Palazzo Medici-Riccardi. The model of the painting had been used by Lippi since as early as 1436, which portrays the Madonna’s half-bust in a niche with a shell-shaped dome, holding the Child. In this case, the Child stands on a marble parapet. The style is however typical of his late career, and therefore the work is generally considered one of the artists’ last panels. Surprisingly, when I walked around the panel, I found a drawing on its back depicting the head of St. Jerome.

Annunciation by Lorenzo di Credi

Lorenzo di Credi is known for his paintings on religious subjects, and he first influenced Leonardo da Vinci and then was greatly influenced by him. The “Annunciation” is among the collections of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and was moved here for the exhibition. In a room of classical architecture, the angel enters from a door on the left and surprises the Virgin, who was reading a book on the lectern on her right. The moment is best captured by the turning posture of the Virgin which can be seen from the wrinkles of her gown. In contrast to the dark architectural elements, the two figures stand out clearly. The large variety of light sources (from the background and from the left) refers to Flemish examples, which was also adopted by Leonardo da Vinci who was a colleague of Lorenzo’s workshop under the common master Verrocchio. However, as I read from Wikipedia, compared to Leonardo, Lorenzo “did not give the composition that atmospheric binder that plunges the figures into the landscape. The protagonists in fact seem simply juxtaposed to the scenography, like very refined but artificial silhouettes.” The landscape is rather curious and causes doubts on the artist’s mastery of aerial perspective as the left part seems to have a higher horizon while the one on the right is excessively blurred by the mist. The lower part of the panel is decorated with a monochrome painting imitating predella and bas-reliefs. Divided by two “pillars”, each of which is adorned with a vase, flowers and a heraldic shield with an eagle(it is the only clue to trace back to the probable original commission of the work), the image show scenes from the Book of Genesis, namely, the Creation of Eve, the Original Sin and the Expulsion from the Earthly Paradise.

Adoration of the Magi by Sandro Botticelli

Together with Leonardo da Vinci’s “Madonna of the Carnation”, which I will talk about in the next section, this painting is probably the most prominent work in the exhibition (at least for me personally). Painted by the Italian Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli, dating from 1475 or 1476, early in his career, it’s among the permanent collections of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It’s surprising that I don’t remember seeing it at all during my visit to the Uffizi but I guess it’s probably because it was on loan to some other galleries at that time or I was too focused on the master’s “The Birth of Venus” and “Primavera”. Anyway, I felt really excited to see it in the Alte Pinakothek. Why? The popular self-portrait of the master is hidden in the crowds. Can you find him?

Botticelli was commissioned to paint various versions of the “Adoration of the Magi” and this one was commissioned by Gaspare di Zanobi del Lama for his funerary chapel in Santa Maria Novella. As commented on the info board, this painting is a “prime example of religious history painting in keeping with contemporary art theory”. In the scene numerous characters are present, among which are several members of the Medici family. In the middle we see Cosimo de’ Medici (the Magus kneeling in front of the Virgin, described by Vasari as “the finest of all that are now extant for its life and vigour”), and his sons Piero (the second Magus kneeling with the red mantle) and Giovanni (the third Magus). Lorenzo il Magnifico and Giuliano de’ Medici, Cosimo de’ Medici’s grandsons, are identified as the two tall men leading the royal retinue on both sides. The three Medicis portrayed as Magi were all dead at the time the picture was painted, and Florence was effectively ruled by Lorenzo. The inclusion of crypto-portraits is likely to have strengthened the impression of directly witnessing a religious play.

Now, let’s come back to the question in the first paragraph and pay attention to the crowd on the right. If you have ever googled Sandro Botticelli, you can probably spot his self-portrait easily. He’s the man in a yellow robe on the right edge of the picture. He proudly presents himself with concealed hands and as such, as an intellectual creator. Please note, when he completed the painting, the artist was only 30 years old, but from his posture and facial expression, we can already see his ambition and confidence. The commissioner can also be seen in the crowd, who is rendered with white hair and in a blue cloak. Both figures draw the viewer into the scene through direct eye contact.

I’ll finish the introduction of the masterpiece by quoting what Vasari writes in his “The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors & Architects”:

“of the heads in this scene is indescribable, their attitudes all different, some full-face, some in profile, some three-quarters, some bent down, and in various other ways, while the expressions of the attendants, both young and old, are greatly varied, displaying the artist’s perfect mastery of his profession. Sandro further clearly shows the distinction between the suites of each of the kings. It is a marvellous work in colour, design and composition.”

Madonna of the Carnation by Leonardo da Vinci

One of the treasures of the Alte Pinakothek is “Madonna of the Carnation” by Leonardo da Vinci, which is the only painting by the master on permanent exhibition in Germany. After the temporary exhibition finishes, it will be moved back and exhibited on the first floor of the galley.

In the setting of a room with two windows on each side of the figures opening onto a mountain landscape, the young Virgin is seated with Baby Jesus on her lap. Depicted in precious clothes and jewellery, Mary holds delicately a carnation in her fingers, for which the Baby reaches out. Some resources say that the flower predicts the Passion, while others state that it’s a healing symbol. The Baby is awake and interacting with his mother rather than asleep and cradled in her arms as he is in many other depictions, which gives this particular image a sense of life. What’s more, the consistent use of light and shade gives the figures a convincing physicality and thus liveliness. One curious thing is that the mother is looking down and the Baby is looking up, but when I expected a deep emotional connection between the two I noticed that there’s no eye contact. Maybe both of them are focusing on the carnation at the moment?

How the work arrived at the Alte Pinakothek after its acquisition by a private German collector is unknown, but what is certain is that its attribution to da Vinci was not immediate. For a period of time, most art historians believed that the work had been created by Verrocchio. Later, it was attributed to da Vinci and more recent research backs up this theory. Many scholars believe it was painted between 1478 and 1480, while some others think it was created as early as 1472, when da Vinci was still working in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, which he joined at the age of 14. In either case, it’s considered one of Leonardo’s first autonomous works. Despite completing his training at the age of 20 in 1472, da Vinci remained loyal to Verrocchio and continued to practice in his workshop for several more years. What are the evidences that support the present-day attribution? First, it is said that one of his drawings shows some of the details which appear in the Virgin’s face and the gem fastening the Virgin’s gown over her breast is reminiscent of that in the master’s another early work “Benois Madonna“. Secondly, the richness of the drapery, the vastness of the mountain scenery, the peaks that fade into the sky, the liveliness of the flowers in the vase, the softness of the Child’s flesh, the cushion on which the Child is seated and the Virgin’s hair and left hand show a distance from the Verrocchiesque style and are more typical of Leonardo, as is the use of chiaroscuro.

Unfortunately, in comparison with other da Vinci paintings, “Madonna with the Carnation” has deteriorated badly, which is especially obvious on the Virgin’s face. Hopefully in the future careful restoration will be conducted to improve its conditioned.

David Victorious by Antonio Pollaiuolo

The most important patron saint of the city of Florence was St. John the Baptist, whose feast day is still celebrated every year on 24th June. Along with others, Judith and David were also highly admired in the 15th century. According to biblical account, David wounded Goliath with his sling and when the giant fell on the ground, David took Goliath’s sword and cut off his head. In Quattrocento Florence, David advanced to become a symbol of the Republic’s ability to defend its freedom in the face of any opponent and the systematic spread of the new representation of patriotism began with the installation of Donatello’s marble “David” in Palazzo della Signoria in 1416. From then on, Goliath’s conqueror become popular in all media, as testified in the field of sculpture by the famous bronze statues by Donatello and Andrea del Verrocchio and later Michelangelo’s monumental marble “David”. The young hero, as shown in the painting by Antonio Pollaiuolo, can be unmistakably recognised through his attributes such as the sling, the sword and Goliath’s head and his distinctive posture with one arm akimbo, showing both pride and confidence. Although the mythological heroes of Antiquity mirrored certain fundamental traits of the human being, as immortal gods, they remained inaccessible. David, on the other hand, was a human who through his courage and trust in God conquered a seemingly invincible enemy.

Autonomous portrait of the 15th century

One of my favourite features of the exhibition is the opportunity it provides to see magnificent masterpieces from all over the world. For example, the “Portrait of a Young Man” by Filippino Lippi is from the National Gallery in Washington D.C., the “Portrait of a Woman in Profile” by Piero Pollaiuolo is from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and the “Portrait of a Woman” by Sandro Botticelli is from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Luckily, I was able to admire and compare them at the same time and same place.

Autonomous portrait is one of the most significant innovations in the art of the 15th century. Within just a few years, portraits emerged in Florence in various media. Whereas sculpted portraits in the Middle Ages served primarily as a visualisation of worldly rulers or princes of the Church and as memoria, the middle class in Florence discovered the art of portraiture for themselves in the middle of the Quattrocento. For the first time since Antiquity, busts once again depicted living people who were neither emperors, kings nor popes, but members of the urban aristocracy. Among the bourgeoisie, painted portrait became established in Florence from the second quarter of the 15th century onwards in the form of portrait busts, that in the case of female sitters, were in strict profile, as this style was considered the most virtuous. Although Netherlandish portraits in three-quarter view had reached the city in the 1440s, side and front views only became common around 1470.

As you can see in the 3rd picture above, Botticelli’s innovative composition, in which a woman sits in three-quarter pose with her hand on the window frame and looks directly at the viewer, made a major contribution to changes in Florentine portrait painting. It is thought to be the first example of a three-quarter pose in Florentine portrait painting and “by abandoning the profile pose traditionally used in depictions of Renaissance women, Botticelli brought a new sense of movement into the portrait.” Based on the old, but probably not original, inscription on the windowsill at the bottom of the picture, the sitter is commonly identified as Esmeralda (Smeralda) Donati Brandini, the wife of Viviano Brandini, mother of the prominent Florentine goldsmith Michelangelo de Viviano de Brandini of Gaiuole, and grandmother of the sculptor Baccio Bandinelli. It has been suggested that the portrait was painted by one of Botticelli’s assistants during the 1470s, but the Victoria and Albert Museum, still attributes it to Botticelli himself.

If you ever saw the advertising of the exhibition either on social media or in the city, I’m sure you’ll find the “Portrait of a Young Man” by Filippino Lippi (as you can see in the 1st picture above) familiar. Transported from the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the young man dressed in the typically plain costume of a wealthy Florentine of that time is the superstar of the show. Filippino Lippi was the son of the painter Fra Filippo Lippi, who was undoubtedly the boy’s first master. After his father died in 1469, he became a pupil of Botticelli, who had a profound influence on him. In fact, the style of the Washington portrait is so close to that of Botticelli that there has been considerable disagreement among scholars as to who is its real creator. In the past, it has been attributed more often to Botticelli than to Filippino, but most recent authors have now agreed that it is by the younger painter because the portrait bears a great resemblance to a young man painted in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence by Filippino in 1483 or 1484, when the artist was assigned the task of finishing Masaccio’s great frescoes.

Secular paintings

Although religious paintings intended for churches or private devotional use dominated the Quattrocento in Florence, artists also worked in other fields of painting. For example, extensive building activities in the 15th century required interior decoration of the palazzi, and paintings became an established component in social conventions (such as presents for family occasions) and local traditions (for example for festival processions through the city). As commented on the info board, “Art expanded the possibilities for creating a personal atmosphere while allowing a demonstration of luxury, prestige and taste at the same time.”

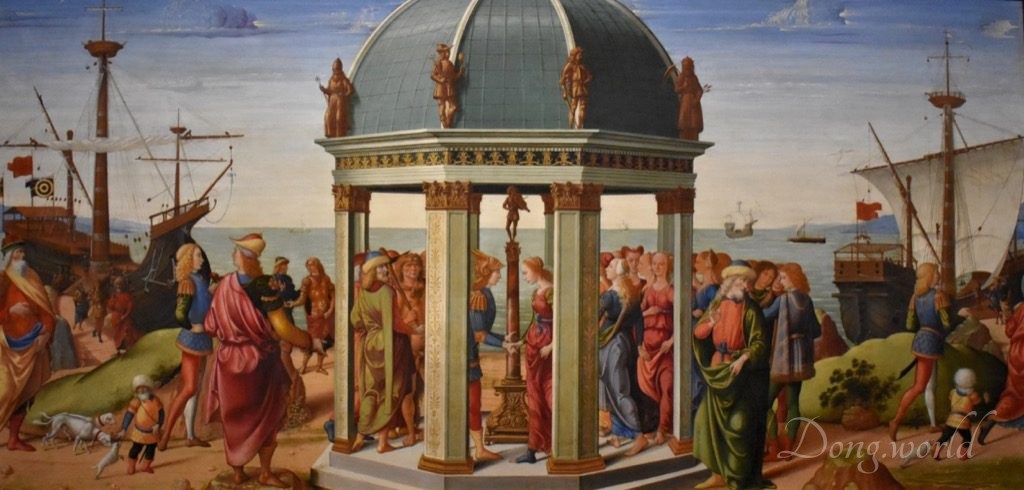

Secular paintings generally carried ethical messages, either on aspects of marital life or on the upbringing of children. Exemplary historia from Antiquity and allegories of virtue were popular while contemporary events were rare. As you can see in the 1st picture above, “The Betrothal of Jason and Medea” by Biagio d’Antonio is a good example. In Greek mythology, Medea was an enchantress who helped Jason, leader of the Argonauts, to obtain the Golden Fleece from her father, King Aeëtes of Colchis. She was of divine descent and had the gift of prophecy. She married Jason and used her magic powers and advice to help him. Clearly, this work praises and delivers the message of loyal and harmonious marriage.

Restoration

The last section of the exhibition is about conservation and restoration of artworks, which was quite interesting for me. I still remember when I was visiting the Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza, the owner took me to visit two of the rooms whose frescoes were under restoration. The process seemed complicated but I didn’t learn much about it. Here in this exhibition, a specific space is dedicated to this theme and one painting by Sandro Botticelli and one by Raffaellino del Garbo are shown to exemplify the differences between conservation and restoration.

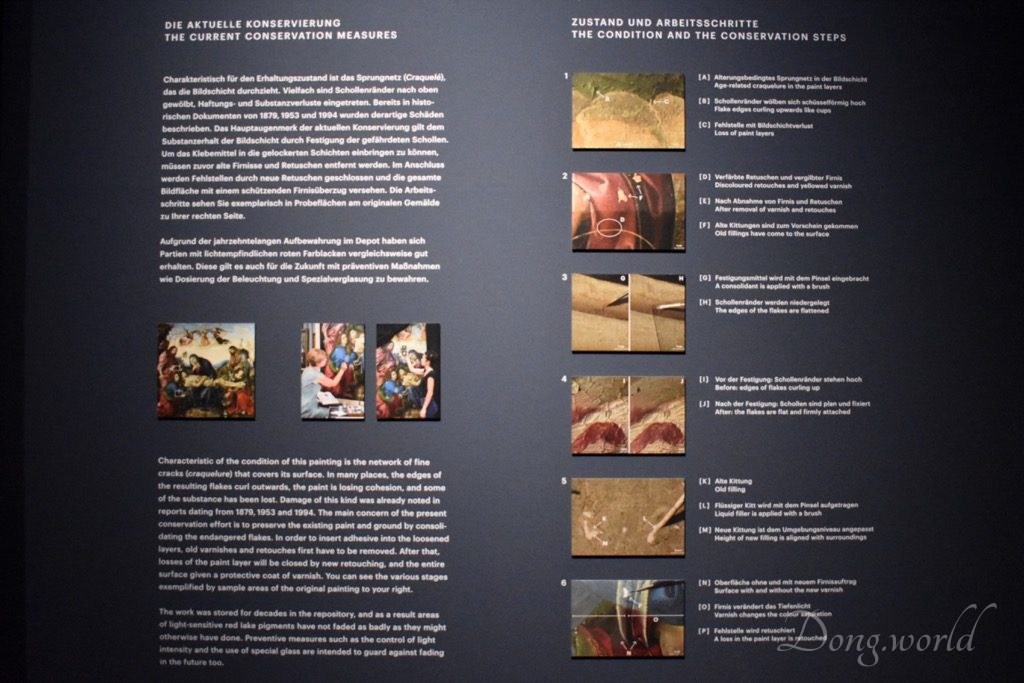

- As exemplified by Raffaellino’s “Lamentation” (as you can see in the 2nd and 3rd pictures above), conservation describes procedures, as a rule largely invisible, designed to ensure the survival of the work for coming generations. The consolidation of flaking paint layers is one such measure.

- As exemplified by Botticelli’s “Lamentation” (as you can see in the 1st picture above), restoration goes a step further and is intended above all to improve the “legibility” of a work, for example, by retouching the losses in the paint layer. Therefore, the effect is visible.

It was after visiting the exhibition that I realised both restoration and conservation are really intricate and time-consuming processes. For example, for Botticelli’s “Lamentation”, the restoration measures were agreed on jointly by conservators, art historians and scientists and the process, which lasted two years, was continuously monitored using a stereomicroscope. As for Raffaellino’s “Lamentation”, which has been stored in the repository for decades, fine cracks cover its surface and in many places, the resulting flakes curl outwards, the paint is losing cohesion and some of the substance has lost. The main concern of the present conservation effort is to preserve the existing paint and ground by consolidating the engendered flakes. Interestingly, various stages are exemplified by sample areas of the original painting on site.

Normally I don’t write about temporary exhibitions but as a huge fan of the Italian Renaissance and the Florentine School, I decided to dedicate a post to “Florence and Its Painters – from Giotto to Leonardo da Vinci”. The show is special as it brought together precious works from all over the world to introduce and explain the artistic development, history and social environment of the Quattrocento Florence. Sadly I only visited the exhibition two weeks before it finishes (3rd February 2019), but when I wrote this post, I alway bore in mind that it should serve the purpose of a reminder to those who have seen it and of a virtual tour to those who can’t make it on time. All in all, I hope you can learn from art, communicate with art and be inspired by art.